Epidemic denial doesn’t add up. Take the US population of 124 million in 1931—the year the eldest child in that first report on autism was born. Divide that number by the current autism prevalence of one in sixty-eight children [2017]. There should have been 1.8 million Americans with autism in 1931. – Denial – Olmsted and Blaxill

Of course, we all know, if there’s no epidemic, there is no environmental trigger, because why have a trigger if something hasn’t actually grown? – Denial - Olmsted and Blaxill

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

There is no autism epidemic.

Oh, sorry, I didn’t realise you were there.

I was practicing my autism epidemic denial.

It’s one of the few “denials” that is not frowned upon.

It’s likely to be my ticket back into civil society.

At some point I’m might need it…the ticket that is.

With thanks to Dan Olmstead and Mark Blaxill for writing Denial.

Please buy and share the book.

Denial: How Refusing to Face the Facts about Our Autism Epidemic Hurts Children, Families, and Our Future

“What Hump?”

Even as the autism toll passes a million children and the cost soars to a trillion dollars, a pernicious idea is taking hold: there simply is no autism epidemic.

The implications are enormous. Is autism ancient, a genetic variation that begs only for overdue acceptance and acknowledgment? Or is it recent and growing, the frightening product of something toxic to which our children are succumbing?

We believe autism is new and the rate really has risen dramatically. “Autism is a public health crisis of historic proportions,” one of us testified to a Congressional Committee in December 2012. Therefore, we as a nation face an obligation to take urgent action against an epidemic of disability that too many “experts” won’t acknowledge, don’t take seriously, or simply deny. They are flat earthers for the new millennium. We call them Epidemic Deniers. They do nothing but confuse the facts about a clear-cut, man-made catastrophe and, unconscionably, delay the day of reckoning and response.

We have learned these truths from our own experience and seen them confirmed day in and day out for many years. One of us is the parent of a daughter with an autism diagnosis who will never live independently. The other has reported on autism for a decade and watched the rate soar even in that short period. Together, we wrote The Age of Autism in 2010, delving deeper into its natural history than ever before, and identifying eight of the first eleven cases in the medical literature, including Case 1, Donald T., whom we visited at his childhood home in Mississippi where he still resides. Those first cases were reported in 1943, a mere tick on history’s timepiece.

Yet today a million and more Americans, almost all of them under thirty, have been formally diagnosed with autism. Yes, it is a spectrum disorder, but variation should not confuse the issue. Most with an autism diagnosis will never be employed, pay taxes, fall in love, get married, have children, or be responsible for their health and welfare. Both the increase and the burden it imposes are widely recognized by thousands of parents and frontline professionals such as nurses and teachers. Yet some of the most prominent and powerful people in medicine, the media, and government deny it.

Rejecting this reality is itself a kind of disorder—Epidemic Denial. It is a little like bug-eyed Marty Feldman as a hunchback in Young Frankenstein, responding to Gene Wilder’s Count Frankenstein with the indignant, “What hump?” It’s the Big Lie about autism. But instead of fading as more and more evidence reveals the scope and scale of autism’s effect on American children, Epidemic Denial is gaining traction, especially from two books that slickly package false logic, weak data, and syrupy nostrums to argue against the very existence of an epidemic.

“… Autistic people have always been part of the human community, though they have often been relegated to the margins of society,” writes Steve Silberman in NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity.

No, they have not. While autistic traits may always have been part of the human profile, their severity and ubiquity have not, and the disability of those with autism is what keeps the vast majority at the margins of society.

John Donvan and Caren Zucker, the authors of In a Different Key: The History of Autism, are dubious about an epidemic but dodge the issue in a way that makes it seem trivial rather than existential. “We don’t really know if there is not an epidemic, but we also think that it shouldn’t matter when we decide whether or not to respond to the needs of people in the autism community,” says Donvan, an ABC News reporter. “It shouldn’t matter whether there’s an epidemic or not.”

Yes, it should. And yes, there is.

Donvan and Zucker are of course right about responding to the needs of those with autism. But they’re dead wrong that the epidemic question doesn’t really matter. How, for one thing, do you plan for the needs of twenty-one-year-olds a decade hence if you don’t concede their numbers will have greatly increased?

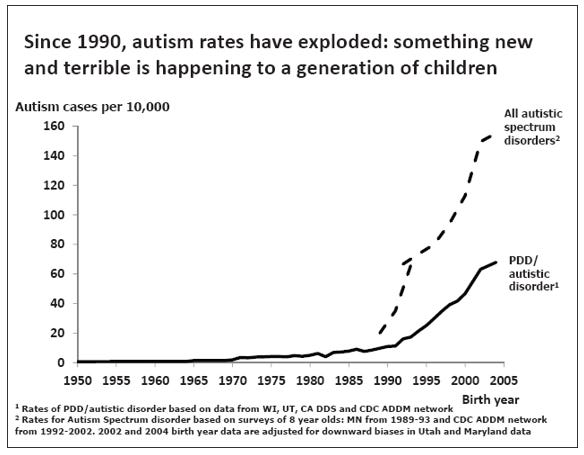

Autism Epidemic Denial belongs in the fiction category. Yet both books have been widely acclaimed. A “magnificent opus,” the Washington Post said of In a Different Key. “A tour de force of archival, journalistic and scientific research, both scholarly and widely accessible,” said chief judge Anne Applebaum of NeuroTribes, the first popular science book to win Britain’s prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize (and $35,000). Mainstream reviewers have proven themselves too indoctrinated, too uninterested, or too incurious to question the dubious premise of these books, which are presented in dulcet tones that echo today’s cultural memes of inclusivity and self-advocacy. Not that anything is wrong with that—but it’s only half the story, the half that screenwriters and TV news segments love to showcase. In the real world, the autism rate is up one hundredfold in the three decades (see chart) with a clear inflection point around 1990, pointing to environmental exposures, not better detection or broader diagnosis.

Even the CDC, charged with determining the autism rate, is blandly agnostic. “Is there an ASD [autism spectrum disorder] epidemic?” the agency asks on its autism page. “A: More people than ever before are being diagnosed with an ASD. It is unclear exactly how much of this increase is due to a broader definition of ASD and better efforts in diagnosis. However, a true increase in the number of people with an ASD cannot be ruled out. We believe the increase in the diagnosis of ASD is likely due to a combination of these factors.”

That’s mush.

Hence, this book. The case against Epidemic Denial is convincing, and we intend to make it forcefully and fully. Upon close examination, Epidemic Denial is not merely improbable or implausible but impossible. The Deniers’ argument falls into a number of logic traps and evidence gaps so deep it can’t get up. Epidemic Deniers simply have not put their ideas to the tests they must survive in order to be taken seriously. We’ll use key evidence from medical history to demonstrate what we mean.

We will show that before 1930, the rate of autism was effectively zero. The rise was slow at first—van Krevelen was looking for the first autism case as late as 1952—but by the late 1980s, it began to accelerate sharply and has since become a feature of life in every community. Last year, educators in Minneapolis announced plans for a high school exclusively for students with an autism diagnosis; a toy store for autistic children opened recently in Chicago. Yet we are to believe this level of special education, this need for accommodation, was present all along and just now provided.

We call bullshit on that.

We had it all and then tried to become gods

Western civilization collapsed because of vaccines.

The Enlightenment died because of vaccines.

The greatest experiment in the history of self-government ended because of vaccines.

Progressivism imploded because of vaccines.

The most powerful economy ever created was turned off because of vaccines.

It’s is absolutely WILD that so much could unravel so quickly because of this worthless toxic product.

Dr. Toby Rogers

Epidemic denial doesn’t add up. Take the US population of 124 million in 1931—the year the eldest child in that first report on autism was born. Divide that number by the current autism prevalence of one in sixty-eight children. There should have been 1.8 million Americans with autism in 1931.

There weren’t. We have scoured the medical literature for cases before then, and there are essentially none to be found. This may seem counterintuitive—surely such children have always been around, misdiagnosed by a less sophisticated medical establishment or simply missed because they were hidden away in an attic or mental institution—but it’s the simple truth.

Back up a bit more: how many people have ever lived on Earth? About 100 billion by 1931. Again, simple math yields about one-and-a-half billion autistic individuals who have lived before 1930.

Now we begin to glimpse the emptiness behind the Epidemic Denier’s claims. There may have been scattered individuals with enough traits to qualify for an autism diagnosis, but 1.5 billion would have been far more visible. Someone would have said something. Given the distinctive profile of autistic children, it’s impossible that no doctor or social observer commented on their markedly different behavior.

Now zoom in again and consider the population of Forest, Mississippi, where Case 1, Donald Triplett, was born in 1933. As Jonathan Rose, a history professor at Drew University, points out, at today’s rate of one in sixty-eight children, there should have been sixty autistic people back then in that small town of three thousand. Donald would have been one of many with similar profiles. There would have been adults, special classes, and dozens of autistic people roaming the streets alongside Donald. Instead, he was an oddity never seen before.

Clearly, he was alone.

So why claim otherwise in the face of both common sense and clear data? Some just assume a condition as well entrenched as autism must always have been around, with the well-known consequences of assuming anything. Others suspect the increase is only too real but find no reason to upset the status quo, the circular round of benefits, grants, breathless gene “breakthroughs” of no real significance—and back to benefits.

And too many do know but let the epidemic roll on in the service of something sinister—saving their reputations, avoiding liability, making money, and in some cases ducking potential criminal liability. They put their careers ahead of our kids. We are not conspiracy theorists; we don’t need to be when so much has been placed in the public record in the past few years.

The question is cui bono—who benefits?

Autism is simply not a feel-good story; it is not about research advances, better understanding, or misunderstood geniuses. The toll of disability from autism rapidly erodes our standing in the world and adds billions to educational services that are already strained. At one prominent US high school with more than three thousand students whose data the authors reviewed confidentially, one in forty-nine has an autism diagnosis—and even then the most severe cases are receiving educational services off-campus and not counted in that total.

Like Neapolitan ice cream, Epidemic Denial comes in three flavors. There’s something to suit the tastes of different audiences—inclusion, diversity, evidence of medical prowess, hidden aptitudes, a wonderful next step in evolution we can barely imagine.

Flavor One wants us to believe that “science,” like some kind of omniscient god, rejects claims of an epidemic. Doctors and the medical field in general love this flavor because it reflects admirably on their powers of observation compared to earlier generations. It fits with the march of medical progress conquering all before it. Michael Crichton, the great popular fiction writer who was also a Harvard-trained MD, took this idea apart as well as anyone we know.

“Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus,” he wrote. “Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world.”

The overall theme of the Deniers is that the so-called autism epidemic is an artifact of better diagnosis. “It’s not an actual epidemic,” as vaccine researcher and patent holder and de facto Denier-in-Chief Paul Offit put it. “In the mid-1990s, the definition of autism was broadened to what is now called autism spectrum disorder. People say if you took the current criteria and went back 50 years, you’d see about as many children with autism then.” No, people don’t say that. They say they waited years for the first sighting, like van Krevelen in Holland. Medical students into the 1970s and ’80s here and abroad gathered round to see a single autistic patient. They were told it might be the only such case in their careers.

The better-diagnosis claim incorporates three elements. One is diagnostic substitution—children previously diagnosed as mentally retarded, for example, now getting a primary diagnosis of autism. The second is diagnostic expansion, in which, say, the inclusion of Asperger’s syndrome on the autism spectrum in 1994 attracted a new cohort of less-severe cases that were previously considered eccentric, not diagnosable. The third is diagnostic oversight, in which hordes of people who should have had an autism diagnosis were simply overlooked.

Offit’s claim is pure diagnostic expansion. Silberman’s argument in NeuroTribes is substitution: “For most of the twentieth century, they [autistic people] were hidden behind a welter of competing labels—Sukhareva’s ‘schizoid personality disorder,’ Despert and Bender’s ‘childhood schizophrenia,’ Robinson and Vitale’s ‘children with circumscribed interests,’ [Temple] Grandin’s initial diagnosis of ‘minimal brain damage,’ and many other labels not mentioned in this book, such as ‘multiplex personality disorder,’ which have fallen out of use.” Zucker and Donvan are big on diagnostic oversight, pointing to holy fools, village savants, and feral children as examples as people who were never counted as part of the autism family.

All this sounds reasonable, but it’s demonstrably wrong, and that’s what matters. Better diagnosing can’t account for a fraction of the well-documented twentyfold increase we’ve seen over just the past two decades. Our colleague J. B. Handley calls Epidemic Denial the “original sin” of autism. “In Offit’s world, there is absolutely no problem here. Things are as they always were, we just understand it better. Of course, we all know, if there’s no epidemic, there is no environmental trigger, because why have a trigger if something hasn’t actually grown? Said differently: Denying the autism epidemic is to deny the suffering of millions of children and their families and also to deny the exploration into the true cause so the epidemic might end.”

To persist in this folly requires not just abdicating common sense—Who are you going to believe, Epidemic Deniers or your own lying eyes?—but ignoring more and more evidence. For instance: In 2009, researchers at the University of California at Davis MIND Institute found “the seven- to eightfold increase in the number of children born in California with autism since 1990 cannot be explained by either changes in how the condition is diagnosed or counted—and the trend shows no sign of abating.” The findings, which appeared in the journal Epidemiology, “also suggest that research should shift from genetics to the host of chemicals and infectious microbes in the environment that are likely at the root of changes in the neurodevelopment of California’s children.”

Flavor Two of Epidemic Denial wants us not only to believe that autism has always been with us, but also that it is mild and useful to society. Silberman: “Asperger’s lost tribe finally emerged from the shadows” to launch all sorts of modern inventions.

A lost tribe of high-functioning, technically gifted individuals with autism whose contribution to the modern world is at long last being recognized? Hardly. Here it’s important to distinguish between autistic traits, such as repetitive rocking or delayed speech, and the diagnosis of Autistic Disorder. Such traits are simply not the same as an autism diagnosis, which requires evidence of significant problems with communication, restricted interests, and social isolation, all by a child’s third birthday. So you can be a nerd or a geek, transfixed by a special topic or possessing savant skills, yet be nowhere near meeting the criteria for the autism spectrum.

Those traits may be exemplified or taken to their extreme by autistic people, but a “dusting” of one of them does not make a person eligible for a disability diagnosis; there is such a thing as human variation that is not pathological. Having traits that are similar to the autism checklist is not autism.

For Silberman, Hans Asperger in Vienna is the hero. He discovered and nurtured the precocious “Little Professors” whose syndrome would eventually bear his name, while in Baltimore the cold and ambitious Leo Kanner focused solely on severe cases and stole credit that was rightly Asperger’s. This kind of biased biography serves Silberman’s purposes, but it’s a speculative mishmash. Neither Kanner nor Asperger were perfect, but they did the world a service by reporting what they saw with detail that has never been surpassed.

NeuroTribes also taps into the phenomenon of people who self-identify as autistic as adults. This trend of “neurodiversity” deserves skepticism, not because it empowers people to make the most of their circumstances—that’s great—but because it is so often used to clobber those of us who believe that autism is an environmental injury, most often disabling, that calls for action. Many such self-diagnosed advocates are suspect. Adults who went to school, got married, started families and successful careers—and then belatedly decided they are autistic—don’t seem terribly disabled. One self-described self-advocate, Michael John Carley, accomplished all that and more, and those who have seen him in public regard him as an intelligent and articulate person who can play political games with the best of them. He began his presentation to a congressional committee in 2012 by saying that because he was autistic he needed more time than other speakers to express himself, a clever move that almost screams “not autistic!”

Is that the same as a child who can’t go to school, can’t speak, let alone get married or participate in the complex identity politics of American society? It is not, even if it comes from a loving place of identifying with an autistic child. There’s no reason to believe Carley has zero autistic traits. But there’s also no reason to believe he would have qualified for a disability diagnosis based on behaviors evident in infancy, as an ASD requires.

By definition, autistic people, or at least the most disabled that constitute the core of the autism crisis, can’t advocate for themselves. For the Michael John Carleys of the autism self-advocacy world to step in and take a voice away from parents of such profoundly disabled children is unjustified. But it’s just the kind of climate Silberman, Donvan, Zucker, Offit, and the rest of the Epidemic Denial crowd encourage and enable.

Flavor Three is exemplified by Donvan and Zucker’s In a Different Key; they can’t be bothered to either confirm or deny an autism epidemic even as they dismiss or neglect most of the evidence that supports it. These authors—who have autism in their family—are more realistic about its severity in the vast majority of cases. But their argument is the least serious, an emotional soufflé of good feelings and “person of the week” happy talk that collapses like soufflés so often do. (The book evolved from scripts of ABC News autism segments they produced, and it reads that way. The glowing Washington Post review begins: “I was on Page 86 … when I began casting the movie.”) Like savvy Hollywood publicists taking a troubled but talented star under their wing, they seem to be intent on promoting autism as a brand that just needs better PR. They relentlessly cite movies, Hollywood celebs, and the national attention autism is receiving. It feels almost churlish to focus on autism as injury or disability when there is so much to celebrate and so many galas to attend!

Is there even an epidemic, in their view? “A competing explanation,” they say without bothering to assess its dubious merits, “held that the rising numbers throughout the 2000s, rather than marking an epidemic, were a case of epidemiology catching up with reality. In this view, autism, regardless of the specific criteria, was probably always a part of the human condition, but one that it took Leo Kanner to bring into focus, followed by several decades of fine-tuning the definition. It was not that autism was spreading to a larger percentage of the human race than in the past, but that society, prior to 1999, had made no intensive effort to go find the people who were already living with autism among them.”

This epidemiological nihilism ends in incoherence. “The lack of evidence of an epidemic was not evidence of no epidemic,” they continue. Say what now? We are supposed to content ourselves with the idea that there might not not be an autism epidemic, or, to turn it around, that one in sixty-eight children might be suffering terribly due to something new in the environment. Or not. How can anyone leave it at that?

Instead, they dwell on rich folks whooping it up for the unfortunates. The book opens with the Night of Too Many Stars gala, where an eleven-year-old blind autistic girl accompanies Katie Perry on the piano for “Firework.” “The men were crying too. All around the theater. In the balcony. In the orchestra. On the stage, off to one side, the show’s host, Jon Stewart, was seen bringing the back of his hand to his cheek, swiping at it.”

Most autism parents cry for different reasons.

Katie Wright, daughter of the founders of Autism Speaks, who saw her son Christian regress after vaccinations, put it this way: “At its very essence regressive autism is about a child losing all the skills and abilities that are necessary to lead a fulfilling independent life. These children lose their speech, gross motor function and even the ability to eat and sleep like normal human beings. Some lucky children regain all the lost skills, but most do not.

“Regressive autism is a catastrophic loss for the child, the child’s traumatized family and our country. It costs a lot to have regressive autism. Additionally the majority of these children have epilepsy, serious GI and immune diseases and most remain profoundly disabled all their lives.”

Bernard Rimland, the pioneering autism researcher and parent to whom we dedicate this book, wrote to one of us in 2003, ridiculing “the supposedly nonexistent increase in prevalence” of autism. He blasted “the creeps who keep trying to pretend that the autism epidemic is not real.” Their “shoddy work in defense of their indefensible theses” should embarrass them and their colleagues, he wrote. “I am reminded of ‘Baghdad Bob,’ the laughable Minister of Information in Iraq, who continued to defend his indefensible position until he finally disappeared.” It was important, Rimland said, to “keep exposing, very professionally, the inadequacy of their work.”

That is the mission of this book.

Chapter 1: Desperately Seeking Gulliver traces the history of childhood mental disorders before the first cluster of autism cases was described. In contrast to the claim of “statistical quicksand … that made comparisons between past and present exercises in guesswork,” we’ll demonstrate that before 1930 childhood mental illness was well-known and extensively documented. Autism was not part of the picture.

Chapter 2: Absence of Evidence: Gulliver in Lilliput looks for broad populations where you would expect to find cases of autism before 1930 if they existed—groups of intellectually disabled and insane children, and records kept by early general practitioners. Here we find almost nothing to suggest autism’s presence.

Chapter 3: Evidence of Absence: The Empty Quadrant hunts for case reports of children with mental illness before 1930 that might conceivably be autism. The results are not encouraging for the Epidemic Denial argument.

Chapter 4: Autism Arrives describes the first clusters of autism in the medical literature—in 1943 in Baltimore by Leo Kanner, and in 1944 in Vienna by Hans Asperger. Autism Epidemic Deniers assert this is a coincidence or—even more fancifully—that Kanner took Asperger’s discovery and claimed it as his own. In truth, the simultaneous rise points to a common source of causation.

Chapter 5: Unqualified Observers examines the multitude of ways Donvan and Zucker and Silberman misunderstand and misstate the roots and rise of autism, creating an alternative universe that suits their purposes but bears little resemblance to unadorned fact.

Chapter 6: The Epidemic and Its Implications looks at the sharp rise in autism cases in the mid-1990s and the grab bag of excuses, including “better diagnosis,” that have been used to deny it, especially the addition of Asperger’s to the psychiatrist’s bible in the autism category. (Hint: Asperger’s is nowhere near enough to account for the twentyfold rise in diagnoses.)

Chapter 7: The Dynamics of Denial shows how powerful interests have doubled down on suppressing the truth of the epidemic. A modern “mob culture” of bullies has emerged to shout down, shame, and exile anyone who questions the no-epidemic mantra or puts forward a threatening environmental theory.

The Epilogue: Normalizing Autism confronts the real-life consequences of denial. When “the bus stops coming,” parents are left to their own devices. When the parents are gone, their adult children become wards of the states. When that happens, the true cost, dimensions, and tragedy of the autism epidemic will be there for all to see. We need to break through this wall of Epidemic Denial now to put an end to the worst childhood health crisis in history.

Thanks for being here.

Please consider a paid subscription.

You will get nothing more for your support, as everything is made freely available. The money simply goes towards recovering some of the cost of this work.

I am always looking for good, personal GMC, covid and childhood vaccination stories. You can write to me privately: unbekoming@outlook.com

If you are Covid vaccine injured, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment

If you want to understand and “see” what baseline human health looks like, watch (and share) this 21 minutes

If you want to help someone, give them a book. Official Stories by Liam Scheff. Point them to a “safe” chapter (here and here), and they will find their way to vaccination.

Here are all eBooks and Summaries produced so far:

FREE Book Summary: The HPV Vaccine on Trial by Holland et al.

FREE Book Summary: Bitten by Kris Newby (Lyme Disease)

FREE Book Summary: The Great Cholesterol Con by Dr Malcolm Kendrick

FREE Book Summary: Propaganda by Edward Bernays

FREE Book Summary: Toxic Legacy by Stephanie Seneff (Glyphosate)

FREE Book Summary: The Measles Book by CHD

FREE Book Summary: The Deep Hot Biosphere by Thomas Gold (Abiogenic Oil)

FREE Book Summary: The Peanut Allergy Epidemic by Heather Fraser

FREE eBook: What is a woman? - “We don’t know yet.”

FREE eBook: A letter to my two adult kids - Vaccines and the free spike protein

The only good thing to come out of the Scamdemic is that awakened parents are finally starting to question the entire childhood vaccine schedule.

https://themillenniumreport.com/2015/03/dr-andrew-moulden-every-vaccine-produces-harm/