It happens rarely, but whenever I do read a newspaper, listen to the radio, or watch television, on a variety of topics, I find myself wondering, “How? How can this happen? How can people be so gullible?” Gatto has an answer and it is disturbing as well as compelling: 20th Century US education. His argument renews gratitude to my father for having given me the chance to dodge full immersion in the homogenizing machine, and makes me more determined than ever to pass this gift of becoming an individual on to my own children. - TANIA AEBI, author of Maiden Voyage; and world record holder, first circumnavigation of the world by a solo female sailor

Individuality is a contradiction of class theory, a curse to all systems of classification. – John Taylor Gatto

Good people wait for an expert to tell them what to do. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that our entire economy depends upon this lesson being learned. – John Taylor Gatto

There are so, so, so many great people I had no idea existed.

Why would I?

They have been purposely placed into my blind spot, as what they have to say is a threatening inconvenience to those who wish to go about their gradual, long-term and oh so patient project.

And so it is that I have finally found John Taylor Gatto.

I found him via the following sequence:

Greenwood (180 Degrees), then Plummer (Tragedy & Hope 101), then Richard Grove then Gatto. 4 steps.

It’s Gatto’s voice in the wonderful, animated video in the masthead.

Once you listen to Gatto and realise the thrust of his work and the point he is trying to teach us, I think you’ll appreciate why I’m so interested in what he has to say. He is teaching us about things way, way up the river in which we swim. It’s fountain knowledge.

Nothing about “how” we have been “schooled” is accidental. At a certain level, that would seem like an obvious point. But if we accept that to be true, then the question becomes one of purpose and intent.

What is the purpose of the schooling we endured?

What was the intent woven into its every cloth?

Who’s intent was it?

I suspect you are not going to like the answers.

We have been socially engineered, with a particular “product” in mind.

Nobody likes to be told that they are the product of a designed manufacturing process.

No free-spirited libertarian hen wants to hear that she exists but for one egg-laying purpose. That she has been homogenized and standardized. That her “own thoughts” and her “own way of thinking” are not her own.

Some of us have fared better than others under the designed psychological onslaught that was our schooling.

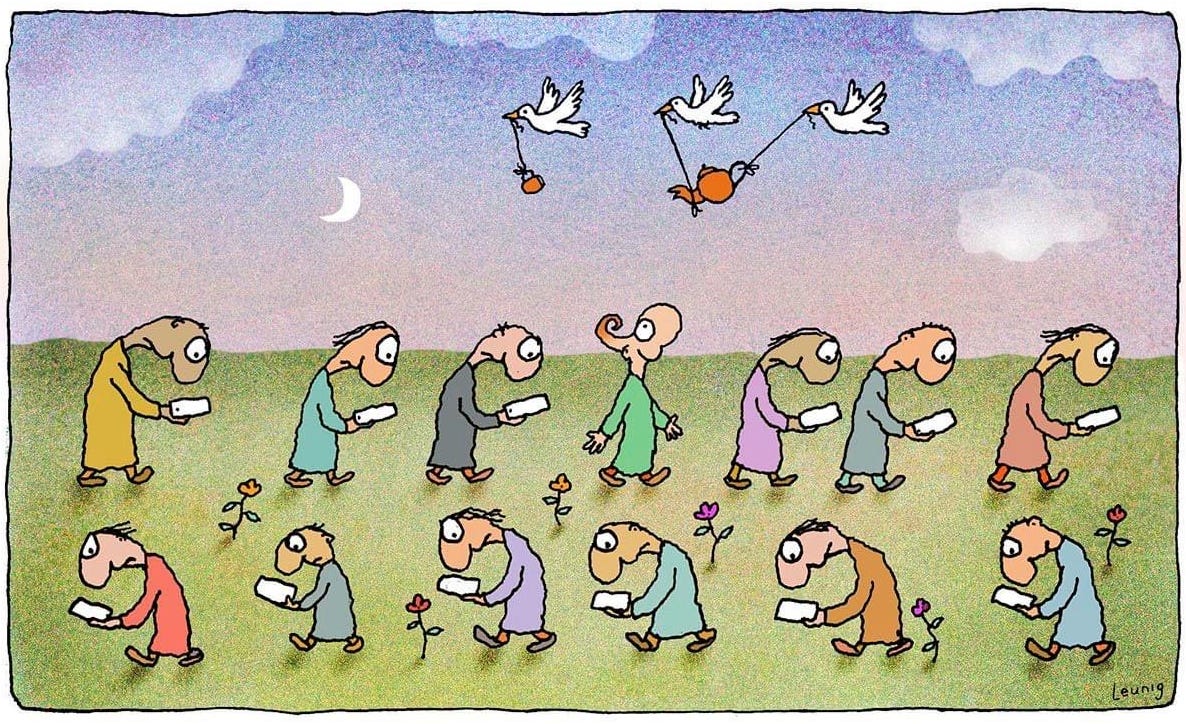

When I look around at how people behaved during the last 3 years, much of what didn’t make sense to me now makes more sense through Gatto’s insights about the incisions made into the global mind. For what was imported, developed, and fine-tuned in America, has been exported, via Empire, to the rest of the world.

Thankfully there is plenty of Gatto content online, still, and I ended up listening to this lecture of his from 2000. I think it’s as good as any to start to get to know the man and his work.

A former New York teacher of the year, Gatto was probably the most interesting writer and speaker of his time on education. He showed that our bureaucratic schools and our bureaucratic society just get in the way of learning. He often contrasted modern America with 19th century America, where family, work, and democratic self-government let people educate themselves. His knowledge of the key players in the history of education was, and probably still is, unparalleled.

In memory of a Great American: John Taylor Gatto December 15, 1935 to October 25, 2018

Read more:

In case you don’t get to listen to his wonderful lecture, here is what the Arabs would say is a “useful summary[i]”.

Comprehensive Summary

The video features a lecture that critically examines the American education system, dissecting its historical roots, underlying motives, and the societal implications of its current structure. Gatto, who is well-versed in the intricacies of the system, argues that modern schooling in the United States serves as a mechanism for producing obedient citizens who are conditioned to accept authority and fit into predefined social roles.

Historical Roots and Influences

Gatto begins by tracing the historical roots of the American education system, pointing out that it has been heavily influenced by private corporate foundations. He mentions the Walsh Commission and the Reece Committee[ii], two significant investigations that concluded that American schooling is not designed for the benefit of the individual but rather serves the interests of these private entities. Gatto also discusses the influence of German educational models, which were designed to suppress self-reliance and promote obedience. He argues that the American system has been modeled after these German systems, incorporating their focus on authority and conformity.

Economic Factors and Industrial Influences

The lecture delves into the economic factors that have shaped the American education system. Gatto talks about the late 19th-century industrial utopia, a period of unprecedented wealth and technological advancement. However, he argues that this came at the cost of personal liberty. The system was designed to produce workers for factories and obedient citizens who would not question the status quo. He also discusses the role of influential industrialists in shaping economic laws and consumer wants, effectively manipulating supply and demand to serve their interests.

The Functions of Schooling

One of the most critical parts of the lecture is the discussion on the functions of schooling as outlined by Alexander Inglis. According to Inglis, the education system serves six primary functions. The first is the adjustive function, which aims to establish fixed habits of reaction to authority. The second is the diagnostic function, where the school determines each student's social role. The third is the sorting function, which sorts children based on their likely roles in society. The fourth is the conformity function, designed to make children as alike as possible to predict their future behavior. The fifth is the hygienic function, which aims to tag the 'unfit' to prevent them from reproducing. The sixth and final function is the propaedeutic function, where a small fraction of students are trained to manage and perpetuate the system.

This sixth function reminded me of this quote from Chris Bray (thanks Toby!):

My argument is not ‘the news media lies,’ or ‘there’s a lot of misleading discourse.’ My argument is that whole overlapping layers of high-status America — in academia, in media, and in politics — are psychotic, fully detached from reality and living in their own bizarre mental construction of a fake world. I don’t mean this figuratively, or as colorful hyperbole. I mean that the top layers of our most important institutions are actually, literally populated by people who are insane, who have cultivated a complete mental descent into a fake world.

Psychological and Societal Implications

Gatto also discusses the psychological impact of this system. He talks about the low threshold of boredom that the system instills in students, conditioning them to require constant novelty and making them more susceptible to advertising and consumer culture. He also discusses the limited mental training provided by the system, arguing that students are not trained to use their minds to their full potential. This, he argues, is a deliberate attempt to produce citizens who are easy to manage.

Contradictions and Paradoxes

The lecture concludes by highlighting the contradictions and paradoxes inherent in the American education system. Gatto points out the paradox of a democratic republic attempting to be an empire, arguing that the contradictions between American ideals and the realities of the system are not resolvable. He also criticizes the term "human resources," arguing that it is dehumanizing and reduces children to mere commodities.

Conclusion

The video serves as a comprehensive critique of the American education system, questioning its underlying motives and exposing its many flaws. It argues that the system is designed to produce obedient, conforming citizens rather than independent thinkers. Gatto calls for a reevaluation of the system and a return to the founding principles of America, which value individual liberty and critical thought over managed consensus and obedience. The lecture serves as a wake-up call, urging the audience to recognize these paradoxes and contradictions and to seek alternatives that align more closely with democratic principles and individual freedoms.

21 Key Takeaways:

1. Origins of Modern Schooling: Gatto traces the roots of the American education system to private corporate foundations.

2. Walsh Commission and Reece Committee: These investigations concluded that the U.S. education system is heavily influenced by private foundations.

3. Economic Leadership: Gatto questions why leaders who claim to be committed to capitalist principles have supported an education system that suppresses individuality.

4. Planetary Governance: Gatto suggests that the elite aim for a form of governance that is more aligned with the British Empire than with American traditions.

5. Industrial Utopia: The late 19th-century promise of unlimited energy and mass production led to unprecedented wealth, but at the cost of personal liberty.

6. Bill of Rights Obstacle: Gatto argues that the Bill of Rights and traditional American ideals stand in the way of this new form of governance.

7. German Models: The U.S. education system is said to be modeled after German systems that aim to suppress self-reliance and promote obedience.

8. Sputnik Crisis: This event was a turning point that led to the full realization of the modern American education system.

9. Functions of Schooling: According to Alexander Inglis, schools serve six functions, including adjustment to authority and sorting by social role.

10. Conformity Over Individuality: Schools aim to make students as similar as possible to predict future behavior.

11. Hygienic Function: Schools are expected to tag the 'unfit' to prevent them from reproducing.

12. Propaedeutic Function: A small fraction of students are trained to manage and perpetuate the system.

13. Obedience to Irrational Commands: Gatto argues that well-schooled people are trained to obey any command, rational or not.

14. Low Threshold of Boredom: The system conditions students to require constant novelty.

15. Limited Mental Training: Students are not trained to use their minds to their full potential.

16. Manipulating Supply and Demand: Gatto discusses how industrialists have rewritten economic laws to control consumer wants.

17. James Bryant Conant: This Harvard president is credited with shaping the modern American high school.

18. Argument vs. Consensus: Gatto argues that America was founded on the principle of argument, not consensus.

19. Human Resources: The term is criticized as dehumanizing, reducing children to mere commodities.

20. Democratic Republic vs. Empire: Gatto points out the paradox of a democratic nation attempting to be an empire.

21. Cost of Security and Ease: Gatto concludes that the comfort achieved through this system comes at the cost of individual souls.

Standout Quotes

*"The establishment of fixed habits of reaction to authority is more important than reading, writing, and arithmetic."

*"You can't trust people who obey only commands grounded in good sense."

*"The security and ease so achieved is purchased at the price of our souls."

*"Our children are not human resources; they are not a workforce."

*"America was given to the world as a place of argument, not as a laboratory of managed consensus."

*"The contradictions between what we say we believe and what we do are not resolvable."

*"Gatto concludes that the comfort achieved through this system comes at the cost of individual souls."

*"To make those things happen requires that most of us will never grow up."

Lastly, I’d like to leave you with Chapter 1 of Gatto’s important book:

Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum... book by John Taylor Gatto (thriftbooks.com)

I know that you will read it with your own schooling in mind, and you should.

You may read it with your children’s schooling in mind, maybe even your grandchildren’s. Again, you should.

But I ask that you also read it with the last 3 years, the GMC, in mind, and with this passage from the great Jeffrey Tucker, in your ear:

The Great Demoralization ⋆ Brownstone Institute

This was the onset of the great demoralization. The message was: your property is not your own. Your events are not yours. Your decisions are subject to our will. We know better than you. You cannot take risks with your own free will. Our judgment is always better than yours. We will override anything about your bodily autonomy and choices that are inconsistent with our perceptions of the common good. There is no restraint on us and every restraint on you.

This messaging and this practice is inconsistent with a flourishing human life, which requires the freedom of choice above all else. It also requires the security of property and contracts. It presumes that if we make plans, those plans cannot be arbitrarily canceled by force by a power outside of our control. Those are bare minimum presumptions of a civilized society. Anything else leads to barbarism and that is exactly where the Austin decision [shutting down South-by-Southwest] took us.

With thanks and gratitude to the late John Taylor Gatto.

“In South Africa, I wrote a teacher training course back in 1997 and hired a team of highly educated ex teachers to go to schools and teach it. It was how to get the willing cooperation of every child in the class. It was so successful we got into several newspapers. I approached the education department and asked if I could teach all the headmasters. After a while, I was called to a meeting with some of the top brass and I was thrilled, till I got there. Three men in suits with stern faces told me straight that my course empowers people and they are having enough trouble already with compliance with the rules from both teachers and headmasters. They explained in no uncertain terms that school was there to create citizens, not to teach the curriculum, and empowered teaches and headmasters would lead to anarchy and chaos.” - @terriannlaws2749 - 6 years ago

Dumbing Us Down

The hidden curriculum of compulsory schooling

Chapter 1

The Seven-Lesson Schoolteacher

This speech was given on the occasion of the author being named “New York State Teacher of the Year” for 1991.

CALL ME MR. GATTO, PLEASE. Thirty years ago, having nothing better to do with myself at the time, I tried my hand at schoolteaching. The license I have certifies that I am an instructor of English language and English literature, but that isn’t what I do at all. I don’t teach English; I teach school — and I win awards doing it.

Teaching means different things in different places, but seven lessons are universally taught from Harlem to Hollywood Hills. They constitute a national curriculum you pay for in more ways than you can imagine, so you might as well know what it is. You are at liberty, of course, to regard these lessons any way you like, but believe me when I say I intend no irony in this presentation. These are the things I teach; these are the things you pay me to teach. Make of them what you will.

1. Confusion

A lady named Kathy wrote this to me from Dubois, Indiana, the other day:

What big ideas are important to little kids? Well, the biggest idea I think they need is that what they are learning isn’t idiosyncratic — that there is some system to it all and it’s not just raining down on them as they helplessly absorb. That’s the task, to understand, to make coherent.

Kathy has it wrong. The first lesson I teach is confusion. Everything I teach is out of context. I teach the un-relating of everything. I teach disconnections. I teach too much: the orbiting of planets, the law of large numbers, slavery, adjectives, architectural drawing, dance, gymnasium, choral singing, assemblies, surprise guests, fire drills, computer languages, parents’ nights, staff- development days, pull-out programs, guidance with strangers my students may never see again, standardized tests, age-segregation unlike anything seen in the outside world ... What do any of these things have to do with each other?

Even in the best schools a close examination of curriculum and its sequences turns up a lack of coherence, a host of internal contradictions. Fortunately the children have no words to define the panic and anger they feel at constant violations of natural order and sequence fobbed off on them as quality in education. The logic of the school-mind is that it is better to leave school with a tool kit of superficial jargon derived from economics, sociology, natural science, and so on than with one genuine enthusiasm. But quality in education entails learning about something in depth. Confusion is thrust upon kids by too many strange adults, each working alone with only the thinnest relationship with each other, pretending, for the most part, to an expertise they do not possess.

Meaning, not disconnected facts, is what sane human beings seek, and education is a set of codes for processing raw data into meaning. Behind the patch- work quilt of school sequences and the school obsession with facts and theories, the age-old human search for meaning lies well concealed. This is harder to see in elementary school where the hierarchy of school experience seems to make better sense because the good-natured simple relationship between “let’s do this” and “let’s do that” is just assumed to mean something and the clientele has not yet consciously discerned how little substance is behind the play and pretense.

Think of the great natural sequences — like learning to walk and learning to talk; the progression of light from sunrise to sunset; the ancient procedures of a farmer, a smithy, or a shoemaker; or the preparation of a Thanksgiving feast. All of the parts are in perfect harmony with each other, each action justifying itself and illuminating the past and the future. School sequences aren’t like that, not inside a single class and not among the total menu of daily classes. School sequences are crazy. There is no particular reason for any of them, nothing that bears close scrutiny. Few teachers would dare to teach the tools whereby dogmas of a school or a teacher could be criticized, since everything must be accepted. School subjects are learned, if they can be learned, like children learn the catechism or memorize the Thirty-nine Articles of Anglicanism.

I teach the un-relating of everything, an infinite fragmentation the opposite of cohesion; what I do is more related to television programming than to making a scheme of order. In a world where home is only a ghost because both parents work, or because of too many moves or too many job changes or too much ambition, or because something else has left everybody too confused to maintain a family relation, I teach students how to accept confusion as their destiny. That’s the first lesson I teach.

2. Class Position

The second lesson I teach is class position. I teach that students must stay in the class where they belong. I don’t know who decides my kids belong there but that’s not my business. The children are numbered so that if any get away they can be returned to the right class. Over the years the variety of ways children are numbered by schools has increased dramatically, until it is hard to see the human beings plainly under the weight of numbers they carry. Numbering children is a big and very profitable undertaking, though what the strategy is designed to accomplish is elusive. I don’t even know why parents would, without a fight, allow it to be done to their kids.

In any case, that’s not my business. My job is to make them like being locked together with children who bear numbers like their own. Or at least to endure it like good sports. If I do my job well, the kids can’t even imagine themselves somewhere else because I’ve shown them how to envy and fear the better classes and how to have contempt for the dumb classes. Under this efficient discipline the class mostly polices itself into good marching order. That’s the real lesson of any rigged competition like school. You come to know your place.

In spite of the overall class blueprint that assumes that ninety-nine percent of the kids are in their class to stay, I nevertheless make a public effort to exhort children to higher levels of test success, hinting at eventual transfer from the lower class as a reward. I frequently insinuate the day will come when an employer will hire them on the basis of test scores and grades, even though my own experience is that employers are rightly indifferent to such things. I never lie outright, but I’ve come to see that truth and schoolteaching are, at bottom, incompatible, just as Socrates said thousands of years ago. The lesson of numbered classes is that everyone has a proper place in the pyramid and that there is no way out of your class except by number magic. Failing that, you must stay where you are put.

3. Indifference

The third lesson I teach is indifference. I teach children not to care too much about anything, even though they want to make it appear that they do. How I do this is very subtle. I do it by demanding that they become totally involved in my lessons, jumping up and down in their seats with anticipation, competing vigorously with each other for my favor. It’s heartwarming when they do that; it impresses everyone, even me. When I’m at my best I plan lessons very carefully in order to produce this show of enthusiasm. But when the bell rings I insist they drop whatever it is we have been doing and proceed quickly to the next work station. They must turn on and off like a light switch. Nothing important is ever finished in my class nor in any class I know of. Students never have a complete experience except on the installment plan.

Indeed, the lesson of bells is that no work is worth finishing, so why care too deeply about anything? Years of bells will condition all but the strongest to a world that can no longer offer important work to do. Bells are the secret logic of school time; their logic is inexorable. Bells destroy the past and future, rendering every interval the same as any other, as the abstraction of a map renders every living mountain and river the same, even though they are not. Bells inoculate each undertaking with indifference.

4. Emotional Dependency

The fourth lesson I teach is emotional dependency. By stars and red checks, smiles and frowns, prizes, honors, and disgraces, I teach kids to surrender their will to the pre- destinated chain of command. Rights may be granted or withheld by any authority without appeal, because rights do not exist inside a school — not even the right of free speech, as the Supreme Court has ruled — unless school authorities say they do. As a schoolteacher, I intervene in many personal decisions, issuing a pass for those I deem legitimate and initiating a disciplinary confrontation for behavior that threatens my control. Individuality is constantly trying to assert itself among children and teenagers, so my judgments come thick and fast. Individuality is a contradiction of class theory, a curse to all systems of classification.

Here are some common ways in which individuality shows up: children sneak away for a private moment in the toilet on the pretext of moving their bowels, or they steal a private instant in the hallway on the grounds they need water. I know they don’t, but I allow them to “deceive” me because this conditions them to depend on my favors. Sometimes free will appears right in front of me in pockets of children angry, depressed, or happy about things outside my ken; rights in such matters can- not be recognized by schoolteachers, only privileges that can be withdrawn, hostages to good behavior.

5. Intellectual Dependency

The fifth lesson I teach is intellectual dependency. Good students wait for a teacher to tell them what to do. This is the most important lesson of them all: we must wait for other people, better trained than ourselves, to make the meanings of our lives. The expert makes all the important choices; only I, the teacher, can determine what my kids must study, or rather, only the people who pay me can make those decisions, which I then enforce. If I’m told that evolution is a fact instead of a theory, I transmit that as ordered, punishing deviants who resist what I have been told to tell them to think. This power to control what children will think lets me separate successful students from failures very easily.

Successful children do the thinking I assign them with a minimum of resistance and a decent show of enthusiasm. Of the millions of things of value to study, I decide what few we have time for. Actually, though, this is decided by my faceless employers. The choices are theirs — why should I argue? Curiosity has no important place in my work, only conformity.

Bad kids fight this, of course, even though they lack the concepts to know what they are fighting, struggling to make decisions for themselves about what they will learn and when they will learn it. How can we allow that and survive as schoolteachers? Fortunately there are tested procedures to break the will of those who resist; it is more difficult, naturally, if the kids have respectable parents who come to their aid, but that happens less and less in spite of the bad reputation of schools. No middle- class parents I have ever met actually believe that their kid’s school is one of the bad ones. Not one single parent in many years of teaching. That’s amazing, and probably the best testimony to what happens to families when mother and father have been well-schooled themselves, learning the seven lessons.

Good people wait for an expert to tell them what to do. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that our entire economy depends upon this lesson being learned. Think of what might fall apart if children weren’t trained to be dependent: the social services could hardly survive — they would vanish, I think, into the recent historical limbo out of which they arose. Counselors and therapists would look on in horror as the supply of psychic invalids vanished. Commercial entertainment of all sorts, including television, would wither as people learned again how to make their own fun. Restaurants, the prepared food industry, and a whole host of other assorted food services would be drastically downsized if people returned to making their own meals rather than depending on strangers to plant, pick, chop, and cook for them. Much of modern law, medicine, and engineering would go too, as well as the clothing business and schoolteaching, unless a guaranteed supply of helpless people continued to pour out of our schools each year.

Don’t be too quick to vote for radical school reform if you want to continue getting a paycheck. We’ve built a way of life that depends on people doing what they are told because they don’t know how to tell themselves what to do. It’s one of the biggest lessons I teach.

6. Provisional Self-esteem

The sixth lesson I teach is provisional self-esteem. If you’ve ever tried to wrestle into line kids whose parents have convinced them to believe they’ll be loved in spite of anything, you know how impossible it is to make self-confident spirits conform. Our world wouldn’t survive a flood of confident people very long, so I teach that a kid’s self-respect should depend on expert opinion. My kids are constantly evaluated and judged.

A monthly report, impressive in its provision, is sent into a student’s home to elicit approval or mark exactly, down to a single percentage point, how dissatisfied with the child a parent should be. The ecology of “good” schooling depends on perpetuating dissatisfaction, just as the commercial economy depends on the same fertilizer. Although some people might be surprised how little time or reflection goes into making up these mathematical records, the cumulative weight of these objective-seeming documents establishes a profile that compels children to arrive at certain decisions about themselves and their futures based on the casual judgment of strangers. Self-evaluation, the staple of every major philosophical system that ever appeared on the planet, is never considered a factor. The lesson of report cards, grades, and tests is that children should not trust themselves or their parents but should instead rely on the evaluation of certified officials. People need to be told what they are worth.

7. One Can’t Hide

The seventh lesson I teach is that one can’t hide. I teach students that they are always watched, that each is under constant surveillance by me and my colleagues. There are no private spaces for children; there is no private time. Class change lasts exactly three hundred seconds to keep promiscuous fraternization at low levels. Students are encouraged to tattle on each other or even to tattle on their own parents. Of course, I encourage parents to file reports about their own child’s waywardness too. A family trained to snitch on itself isn’t likely to conceal any dangerous secrets.

I assign a type of extended schooling called “homework,” so that the effect of surveillance, if not the surveillance itself, travels into private households, where students might otherwise use free time to learn something unauthorized from a father or mother, by exploration or by apprenticing to some wise person in the neighborhood. Disloyalty to the idea of schooling is a devil always ready to find work for idle hands.

The meaning of constant surveillance and denial of privacy is that no one can be trusted, that privacy is not legitimate. Surveillance is an ancient imperative, espoused by certain influential thinkers, a central prescription set down in The Republic, The City of God, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, New Atlantis, Leviathan, and a host of other places. All the childless men who wrote these books discovered the same thing: children must be closely watched if you want to keep a society under tight central control. Children will follow a private drummer if you can’t get them into a uniformed marching band.

It is the great triumph of compulsory government monopoly mass schooling that among even the best of my fellow teachers, and among even the best of my students’ parents, only a small number can imagine a different way to do things. “The kids have to know how to read and write, don’t they?” “They have to know how to add and subtract, don’t they?” “They have to learn to follow orders if they ever expect to keep a job.”

Only a few lifetimes ago things were very different in the United States. Originality and variety were common currency; our freedom from regimentation made us the miracle of the world; social-class boundaries were relatively easy to cross; our citizenry was marvelously confident, inventive, and able to do much for themselves independently, and to think for themselves. We were something special, we Americans, all by ourselves, without government sticking its nose into and measuring every aspect of our lives, without institutions and social agencies telling us how to think and feel. We were something special, as individuals, as Americans.

But we’ve had a society essentially under central control in the United States since just after the Civil War, and such a society requires compulsory schooling — government monopoly schooling — to maintain itself. Before this development schooling wasn’t very important anywhere. We had it, but not too much of it, and only as much as an individual wanted. People learned to read, write, and do arithmetic just fine anyway; there are some studies that suggest literacy at the time of the American Revolution, at least for non-slaves on the Eastern seaboard, was close to total. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense sold 600,000 copies to a population of 3,000,000, of whom twenty percent were slaves and fifty percent indentured servants.

Were the Colonists geniuses? No, the truth is that reading, writing, and arithmetic only take about one hundred hours to transmit as long as the audience is eager and willing to learn. The trick is to wait until someone asks and then move fast while the mood is on. Millions of people teach themselves these things — it really isn’t very hard. Pick up a fifth-grade math or rhetoric textbook from 1850 and you’ll see that the texts were pitched then on what would today be considered college level. The continuing cry for “basic skills” practice is a smoke screen behind which schools preempt the time of children for twelve years and teach them the seven lessons I’ve just described to you.

The society that has come increasingly under central control since just before the Civil War shows itself in the lives we lead, the clothes we wear, the food we eat, and the green highway signs we drive by from coast to coast, all of which are the products of this control. So too, I think, are the epidemics of drugs, suicide, divorce, violence, and cruelty, as well as the hardening of class into caste in the United States, products of the dehumanization of our lives, of the lessening of individual, family, and community importance — a diminishment that proceeds from central control. Inevitably, large compulsory institutions want more and more, until there isn’t any more to give. School takes our children away from any possibility of an active role in community life — in fact, it destroys communities by relegating the training of children to the hands of certified experts — and by doing so it ensures our children cannot grow up fully human. Aristotle taught that without a fully active role in community life one could not hope to become a healthy human being. Surely he was right. Look around you the next time you are near a school or an old people’s reservation if you wish a demonstration.

School, as it was built, is an essential support system for a model of social engineering that condemns most people to be subordinate stones in a pyramid that narrows as it ascends to a terminal of control. School is an artifice that makes such a pyramidical social order seem inevitable, even though such a premise is a fundamental betrayal of the American Revolution. From Colonial days through the period of the Republic we had no schools to speak of — read Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography for an example of a man who had no time to waste in school — and yet the promise of democracy was beginning to be realized. We turned our backs on this promise by bringing to life the ancient pharaonic dream of Egypt: compulsory subordination for all. That was the secret Plato reluctantly transmitted in The Republic when Glaucon and Adeimantus extort from Socrates the plan for total state control of human life, a plan necessary to maintain a society where some people take more than their share. “I will show you,” says Socrates, “how to bring about such a feverish city, but you will not like what I am going to say.” And so the blueprint of the seven-lesson school was first sketched.

The current debate about whether we should have a national curriculum is phony. We already have a national curriculum locked up in the seven lessons I have just outlined. Such a curriculum produces physical, moral, and intellectual paralysis, and no curriculum of content will be sufficient to reverse its hideous effects. What is currently under discussion in our national hysteria about failing academic performance misses the point. Schools teach exactly what they are intended to teach and they do it well: how to be a good Egyptian and remain in your place in the pyramid.

None of this is inevitable. None of it is impossible to overthrow. We do have choices in how we bring up young people: there is no one right way. If we broke through the power of the pyramidical illusion we would see that. There is no life-and-death international competition threatening our national existence, difficult as that idea is even to think about, let alone believe, in the face of a continual media barrage of myth to the contrary. In every important material respect our nation is self-sufficient, including in energy. I realize that idea runs counter to the most fashionable thinking of political economists, but the “profound transformation” of our economy these people talk about is neither inevitable nor irreversible.

Global economics does not speak to the public need for meaningful work, affordable housing, fulfilling education, adequate medical care, a clean environment, honest and accountable government, social and cultural renewal, or simple justice. All global ambitions are based on a definition of productivity and the good life so alienated from common human reality that I am convinced it is wrong and that most people would agree with me if they could perceive an alternative. We might be able to see that if we regained a hold on a philosophy that locates meaning where meaning is genuinely to be found — in families, in friends, in the passage of seasons, in nature, in simple ceremonies and rituals, in curiosity, generosity, compassion, and service to others, in a decent independence and privacy, in all the free and inexpensive things out of which real families, real friends, and real communities are built — then we would be so self-sufficient we would not even need the material “sufficiency” which our global “experts” are so insistent we be concerned about.

How did these awful places, these “schools,” come about? Well, casual schooling has always been with us in a variety of forms, a mildly useful adjunct to growing up. But “modern schooling” as we now know it is a by-product of the two “Red Scares” of 1848 and 1919, when powerful interests feared a revolution among our own industrial poor. Partly, too, total schooling came about because old-line “American” families were appalled by the native cultures of Celtic, Slavic, and Latin immigrants of the 1840s and felt repugnance toward the Catholic religion they brought with them. Certainly a third contributing factor in creating a jail for children called “school” must have been the consternation with which these same “Americans” regarded the movement of African-Americans through the society in the wake of the Civil War.

Look again at the seven lessons of school teaching: confusion, class position, indifference, emotional and intellectual dependency, conditional self-esteem, and surveillance. All of these lessons are prime training for permanent underclasses, people deprived forever of finding the center of their own special genius. And over time this training has shaken loose from its original purpose: to regulate the poor. For since the 1920s the growth of the school bureaucracy as well as the less visible growth of a horde of industries that profit from schooling exactly as it is, has enlarged this institution’s original grasp to the point that it now seizes the sons and daughters of the middle classes as well.

Is it any wonder Socrates was outraged at the accusation he took money to teach? Even then, philosophers saw clearly the inevitable direction the professionalization of teaching would take, that of preempting the teaching function, which, in a healthy community, belongs to everyone.

With lessons like the ones I teach day after day it should be little wonder we have a real national crisis, the nature of which is very different from that proclaimed by the national media. Young people are indifferent to the adult world and to the future, indifferent to almost everything except the diversion of toys and violence. Rich or poor, school children who face the twenty-first century cannot concentrate on anything for very long; they have a poor sense of time past and time to come. They are mistrustful of intimacy like the children of divorce they really are (for we have divorced them from significant parental attention); they hate solitude, are cruel, materialistic, dependent, passive, violent, timid in the face of the unexpected, addicted to distraction.

All the peripheral tendencies of childhood are nourished and magnified to a grotesque extent by schooling, which, through its hidden curriculum, prevents effective personality development. Indeed, without exploiting the fearfulness, selfishness, and inexperience of children, our schools could not survive at all, nor could I as a certified schoolteacher. No common school that actually dared to teach the use of critical thinking tools — like the dialectic, the heuristic, or other devices that free minds should employ — would last very long before being torn to pieces. In our secular society, school has become the replacement for church, and like church it requires that its teachings must be taken on faith.

It is time that we squarely face the fact that institutional schoolteaching is destructive to children. Nobody survives the seven-lesson curriculum completely unscathed, not even the instructors. The method is deeply and profoundly anti-educational. No tinkering will fix it. In one of the great ironies of human affairs, the massive rethinking the schools require would cost so much less than we are spending now that powerful interests cannot afford to let it happen. You must understand that first and foremost the business I am in is a jobs project and an agency for letting contracts. We cannot afford to save money by reducing the scope of our operation or by diversifying the product we offer, even to help children grow up right. That is the iron law of institutional schooling — it is a business, subject neither to normal accounting procedures nor to the rational scalpel of competition.

Some form of free-market system in public schooling is the likeliest place to look for answers, a free market where family schools and small entrepreneurial schools and religious schools and crafts schools and farm schools exist in profusion to compete with government education. I’m trying to describe a free market in schooling exactly like the one the country had until the Civil War, one in which students volunteer for the kind of education that suits them even if that means self-education. It didn’t hurt Benjamin Franklin that I can see. These options exist now in miniature, wonderful survivals of a strong and vigorous past, but they are available only to the resourceful, the courageous, the lucky, or the rich. The near impossibility of one of these better roads opening for the shattered families of the poor or for the bewildered host camped on the fringes of the urban middle class suggests that the disaster of seven-lesson schools is going to grow unless we do something bold and decisive with the mess of government monopoly schooling.

After an adult lifetime spent teaching school, I believe the method of mass schooling is its only real content. Don’t be fooled into thinking that good curriculum or good equipment or good teachers are the critical determinants of your son’s or daughter’s education. All the pathologies we’ve considered come about in large measure because the lessons of school prevent children from keeping important appointments with themselves and with their families to learn lessons in self-motivation, perseverance, self-reliance, courage, dignity, and love — and lessons in service to others, too, which are among the key lessons of home and community life.

Thirty years ago these lessons could still be learned in the time left after school. But television has eaten up most of that time, and a combination of television and the stresses peculiar to two-income or single-parent families has swallowed up most of what used to be family time as well. Our kids have no time left to grow up fully human and only thin-soil wastelands to do it in.

A future is rushing down upon our culture that will insist that all of us learn the wisdom of nonmaterial experience; a future that will demand as the price of survival that we follow a path of natural life that is economical in material cost. These lessons cannot be learned in schools as they are. School is a twelve-year jail sentence where bad habits are the only curriculum truly learned. I teach school and win awards doing it. I should know.

Thanks for being here.

Please consider a paid subscription. You will get nothing more for your support, as everything is made freely available. The money goes towards covering the costs of this work, medical freedom causes and support for the vaccine injured.

I am always looking for good, personal GMC, covid and childhood vaccination stories. You can write to me privately: unbekoming@outlook.com

If you are Covid vaccine injured, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment

If you want to understand and “see” what baseline human health looks like, watch (and share) this 21 minutes

If you want to help someone, give them a book. Official Stories by Liam Scheff. Point them to a safe chapter (here and here), and they will find their way to vaccination.

Here are all eBooks and Summaries produced so far:

FREE Summary: Bitten by Kris Newby (Lyme Disease)

FREE Summary: The Great Cholesterol Con by Dr Malcolm Kendrick

FREE Summary: Propaganda by Edward Bernays

FREE Summary: Toxic Legacy by Stephanie Seneff (Glyphosate)

FREE Summary: The Measles Book by CHD

FREE Summary: The Deep Hot Biosphere by Thomas Gold (Abiogenic Oil)

FREE Summary: The Peanut Allergy Epidemic by Heather Fraser

FREE eBook: A letter to my two adult kids - Vaccines and the free spike protein

[i] GPT4 assisted

[ii] The Walsh Commission

The Walsh Commission, formally known as the Commission on Industrial Relations, was created in 1912 in the United States. It was headed by Senator Frank P. Walsh and aimed to investigate labor disputes and the role of philanthropic foundations and industrial organizations in these disputes. One of the most well-known subjects of its inquiry was the Rockefeller Foundation's involvement in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company and the Ludlow Massacre.

Sources:

The Commission on Industrial Relations, 1912–1915, Melvyn Dubofsky, Industrial and Labor Relations Review JSTOR Link

The Reece Commission

The Reece Commission was an investigation initiated by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1952, headed by Congressman B. Carroll Reece. This commission aimed to investigate tax-exempt foundations to determine if they were engaged in activities that could be considered un-American or subversive. Although the commission did find some instances where foundations supported controversial causes, the investigation ultimately led to minimal legislative action.

Sources:

Tax-Exempt Foundations: Hearings Before the Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations, U.S. House of Representatives, 82nd Congress, Second Session on H. Res. 561 (1952).

Share this post