"You knew what you signed up for."

Interview with Chase Spears on military culture and politics, institutional conformity, civil-military relations, vaccination mandates, and much more.

After two decades in the U.S. Army, Chase Spears has experienced the institution from all angles—enlisted soldier to officer, combat camera operator to public affairs leader, Pentagon insider to front-line communicator. His career was shaped by a deep respect for service but also an unflinching commitment to truth, even when it placed him at odds with the military's culture of rigid hierarchy and political maneuvering. In this interview, Spears reflects on the evolution of his views, the widening civil-military divide, and the ethical challenges of serving in an institution that demands both loyalty and silence.

From the post-9/11 surge in military recruitment to the unprecedented pressures of the COVID-19 era, Spears witnessed firsthand the transformation of the armed forces—not just in policy but in philosophy. He discusses the weight of institutional conformity, the moment he realized the military was inherently political, and why he ultimately walked away from a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel. His insights offer a rare, candid look into the realities of military life, the costs of principled leadership, and what it truly means to serve.

With thanks to Chase Spears.

Dr. Chase Spears – Leader | Communicator | Adventurer

1. Chase, after 20 years of military service, including roles from enlisted personnel to Major, what initially drew you to serve in the U.S. Army?

This question makes me think of Proverbs 16:9: “A man’s heart plans his way, but the LORD directs his steps.” Had you known me as a kid or young man, nothing about my personality, my interests, or even my physical build would have suggested a future in the military. The Army wasn’t on my radar. It wasn’t Plan B, C, D, or even Plan Z.

My dad and grandfather had served, and we respected military service. But nothing about it appealed to me—especially the physical fitness requirements. I grew up overweight, and the thought of running anywhere terrified me. Now, my brother? He had the build and personality of a Marine. If anyone in our family was meant to wear a military uniform, it was him.

Ultimately, necessity drew me to the Army. I married my college sweetheart while we were undergraduate students at Lee University. I was working toward a degree in news broadcasting with plans to become a journalist. But the job market for aspiring broadcasters was in a state of collapse due to nationwide media consolidation in the wake of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. CNN, the biggest employer in Atlanta—our nearest major media market—laid off 400 people during my junior year. The situation was so bad that I couldn’t even get an unpaid internship because the market was flooded with recent graduates trying to get a toe in the door anywhere that would have us. We moved to Knoxville after Lori graduated so I could pursue a master’s in journalism—believing a graduate education would set me apart to newsroom employers. I soon learned the hard way that experience trumps credentialing.

Seeing no avenue into journalism on the horizon, I reflected on other passions. Law is another profession I was interested in. But law school is a major life commitment. Lori and I agreed that it would be wise to work part time in a law firm while finishing my journalism studies. This would allow me to get a feel for that line of work, and hopefully help with my application to the University of Tennessee Law School. As it turned out, I did not enjoy the law firm experience. But that job set me on a path I never expected.

One day, while filing paperwork at the Knox County courthouse, I shared an elevator ride with an Army recruiter, Staff Sgt. Robert K. Lusk. He was in his dress uniform, looking sharp, and we struck up a conversation. This was mid-2003, right after the U.S. had defeated Saddam Hussein’s military, and I was impressed by our armed forces. Ever the skilled recruiter, Lusk got my number before we reached our destination floor.

I wrestled with the idea of enlisting over the next seven months. The Army offered a stable way to provide for my wife and our newborn son, and pay off student loans. Staff Sgt. Lusk told me about this career field called public affairs, which was a peer to civilian journalism. It made sense to enlist, but my confidence in succeeding as a military man was low. I was overweight and had never been in an environment that demanded rigid adherence to standards. I couldn’t run much farther than to the mailbox without feeling like my body was going to collapse. But it became clear that the doors I was pounding on in the civilian market were not budging. As a compromise, I tried reaching out to Air Force recruiters. But it seemed in Knoxville, their quotas were met and they weren’t interested in talking. So one day Lori and I had a short and serious discussion. She fully supported me enlisting.

The news came as a shock to my family. My dad, a veteran of the Vietnam era, told me that I didn’t have the discipline to make it in the Army. Another close family member told me years later the consensus was that I wouldn’t make it through basic training. But I did make it through basic training, and several other military schools in years to come.

I became the first military officer in my paternal line, the first officer since the Revolutionary War going up my mother’s family tree, the first paratrooper, and sole veteran of the war in Afghanistan among my family. Dad quickly abandoned his doubts and became a huge fan of my being a soldier. Shortly before losing his battle to cancer, he asked me to wear full military dress at his funeral. I made that promise, and kept it.

Necessity brought me to the Army. But love of being a soldier kept me in for two decades.

2. You've had a fascinating journey from combat camera operations to public affairs leadership. How did your early experiences shape your understanding of military-civilian relationships?

Early on, I noticed a friction between the military and civilian mindset. I remember a drill sergeant openly bragging about his hatred for civilians one day at basic training. I thought to myself, Isn’t our purpose to protect them? A few months later, a supervisor criticized me for calling my peers by their first names. “That soldier has rank,” she said. It seemed silly then, and it still does today. Even after 20 years, I preferred for people to call me by name rather than rank. The officer side of the Army is better about that. You call superior officers Sir or Ma’am,’ but it’s expected for peers and seniors to call you by first name.

As time went on, I saw how deeply the military is built on a culture of separation from civil society. We work—and many troops live—on gated bases. A car isn’t just a car; it’s a POV (privately owned vehicle). In the military, Velcro is “hook pile and loop tape.” These linguistic differences are symptoms of a broader separatist culture.

Serving in public affairs kept me close to civilians. I made a conscious effort to stay proficient in the Queen’s English and remain relatable to journalists and news producers. Simple things—like saying, “Hi, this is Chase calling,” instead of “This is Captain Spears calling for…”—mattered to me. It helped build strong relationships with journalists. But that approach often put me at odds with others in my unit.

One brigade commander I served under despised the press and made a point of regularly reminding me. He saw my rapport with journalists as a liability. It felt like he perceived that I was being too collegial with the wrong team, and kept me at arm’s length because of it. Many of the best public affairs officers (PAOs) face similar challenges—it can be a battle against the military to serve in the military as a public-facing communicator.

Attending the Army’s Command and General Staff College in 2018 deepened my understanding of the civil-military divide.

One block of coursework examined the often-fractious history between civilian leadership and the military in the post-industrial-era age of a ‘professionalized’ standing force. In this paradigm, senior military officials believe that the role of civilians is to keep the institution well supplied in funding and bodies, and butt out of all else. Unfortunately, American civil society has acquiesced, leaving the military to be its own god and conscience. That has led to tremendous abuses that I’ll talk more about later in the conversation.

3. During your time at the Pentagon in 2017, you mention first noticing the political nature of military institutions. What specific observations led to this realization?

In 2017, I served a part-time stint at the Army’s Office of the Chief of Public Affairs while participating in a fellowship at Georgetown University. The Army had selected me through a competitive process to earn a master’s degree in public relations and corporate communication. The program focused on strategic communication, with an emphasis on writing for publication. I began experimenting with that skill and succeeded in getting an essay published in The Baltimore Sun.

The piece was critical of the Army’s public relations handling of Bowe Bergdahl’s deliberate 2009 abandonment of his unit in Afghanistan. It received far more attention than I anticipated—even getting listed on Drudge Report. My superiors at the Pentagon were not pleased. They threatened to bring me before the Army’s Chief of Public Affairs for a wire brushing. I told the colonel delivering the warning that I’d take whatever they threw at me like a man. No further threats came. But it was clear that the office did not actually believe in open communication with the public, despite what Army regulations mandated. One officer on staff pulled me aside and admonished “Chase you can’t do that.” I replied that my actions were in accordance with the military’s regulations on writing. He dismissed that defense, saying that regulations don’t matter, I still couldn’t criticize the Army in writing. That moment opened my eyes to the gulf between the military’s formal rules and its institutional norms.

The colonel I worked for tried to win me over to the system, explaining that everything the Army officially says is nationally strategic. He explained that every piece of information released is coordinated with legal and legislative affairs to ensure alignment between military and political actors. That revelation stood in stark contrast to the public affairs motto: “Maximum Disclosure, Minimum Delay.” It also clashed with the military’s self-proclaimed status as an apolitical institution. How could the Army be non-political when it prioritized vetting its statements through political liaisons rather than simply following its own rulebook?

This was something I wrestled with over the next few months. I observed how communication planning was more focused on pleasing policymakers—the ones who control the budget—than on fulfilling the military’s Title 10 responsibility to keep the public well-informed about military activities.

Then one day, while driving to the Metro rail stop in Suitland, Maryland, a realization hit me: military activities cannot be apolitical. The military is a Presidential cabinet agency. Its top leaders are political appointees. It employs deadly force in support of foreign policy objectives—which are, by definition, political. Even my own promotion orders to the rank of Major required Senate confirmation.

If politics is about power, decision-making, and how societies are organized, there’s no clearer example of those things than the Department of Defense.

I was reassigned to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas next year, where I came across the writings of 19th-century Prussian military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz. He had written of the military’s political nature nearly 200 years ago in his treatise titled On War. As it turns out, nearly everyone who writes in-depth about the military acknowledges its political realities. Most militaries around the world wouldn’t find that argument controversial. Yet in the West, we still cling to the pithy claim of an apolitical military.

Why?

That question led me to my dissertation research, where I traced the origins of this idea. Spoiler alert: It’s rooted in the voting preferences of WWII General George C. Marshall.

4. Your story describes a profound shift in how you viewed the phrase "You knew what you signed up for." How did your understanding of this statement evolve throughout your service?

There’s some truth to the old adage “you knew what you signed up for” when joining the military. No one is surprised that soldiers wake up early, run long distances, learn to shoot, and deploy to potentially dangerous locations. Those are givens. In basic training, we’re taught the limits of free speech for military members. For example, troops can’t make obscene remarks about elected officials or the chain of command to maintain good order and discipline. We can’t wear a uniform to a political rally that’s sponsored by a political party. These restrictions are spelled out in military regulations and the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

But there are also unspoken restrictions—ones that go beyond anything we actually sign up for. I remember in 2004 hearing a staff sergeant at Fort Meade, MD yelling at a group of soldiers that they were all property of Uncle Sam. I thought he was just trying to sound tough. I didn’t sign away my life as a piece of property to anyone when enlisting; though, it became clear later in my career that his perspective was shared among others.

I became acclimated to the formal and tacit restrictions placed upon me as a military member over time. Occasionally, people who sensed my passion for discussing domestic politics would warn me to keep my thoughts to myself because “you knew what you signed up for.” I didn’t like it, but usually nodded along. This was not because I actually agreed with the charge that I signed away my First Amendment rights to be a soldier. Rather, I had simply learned to navigate the military culture, despite my best efforts to stay connected to my identity as a citizen.

It wasn’t until 2018, during the final months of my Georgetown University fellowship, that I fully grasped how far some were willing to take that phrase. A colonel who disapproved of my writing for publication told me bluntly: “When you became a PAO, you gave up your right to an opinion.” He went on to say that I was only allowed to say things that aligned with approved Army messaging.

I found that statement not only offensive but also ignorant. At no point had I signed away my right to think or speak freely beyond the limits I already understood as a military officer. And if I was truly only authorized to speak in pre-approved Army soundbites, would I need a disclaimer for every off-duty conversation? Imagine how absurd that would be:

"Happy birthday, son. I love you. To be clear, this is my personal opinion and does not reflect the position of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government."

It’s a ridiculous thought—but sometimes, you have to meet absurdity with absurdity to fully expose a fallacy. I never accepted that colonel’s claim that I had voluntarily ceded all expressive right. But I remained aware that my perspective on remaining a citizen was in the minority among most others in the military institution.

The military’s response to Covid-19 shattered any lingering doubt that the military institution—and much of the civilian public—believe service members surrender not just some rights, but all rights. I chose not to take the Covid shot when it was voluntary and believed it should remain that way. A family friend I had known since my teenage years challenged me on Facebook, saying that as a soldier, I knew what I signed up for and should take whatever substances the military dictates.

That was the moment the dam broke.

It hit me that the same people who wave the flag and profess to support the troops actually believe that we rank below them as citizens. It’s a despicable social doctrine that flies in the face of George Washington’s words:

"When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen."

That truth has been almost entirely lost—both within the military and in American public consciousness. I never heard it in military training, nor encountered it in civic education.

I discovered it by chance—etched in stone at Arlington National Cemetery.

Fitting, really. There in a graveyard is where today’s military would prefer such truth remain.

5. Can you walk us through the atmosphere at Fort Leavenworth when the Covid-19 vaccination requirements were implemented? What changes did you observe in day-to-day operations?

The Department of Defense’s response to Covid-19, beginning in March 2020, shook my confidence in the military leadership’s ability to accurately assess threats and respond appropriately. Some policies came from the highest levels—such as the Army’s temporary halt on all personnel moves—even before then-Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s illegal vaccine mandate. But individual base commanders had flexibility in how to modify local policies and operations.

At Fort Leavenworth, the response quickly devolved into a showcase of overreach and contradiction. Unlike most Army bases, where enlisted soldiers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs: sergeants through sergeants major) comprise the majority of population, Leavenworth is home to several large headquarters and Army colleges. As such, the base is overwhelmingly populated by officers. Having served on both sides, I often remarked that officers need NCO supervision—because sergeants bring common sense. Without them, officers fall victim to the bright idea fairy, engaging in games of decision one-upmanship to impress their superiors. At Leavenworth, that resulted in policy decisions that contradicted basic knowledge about respiratory viruses.

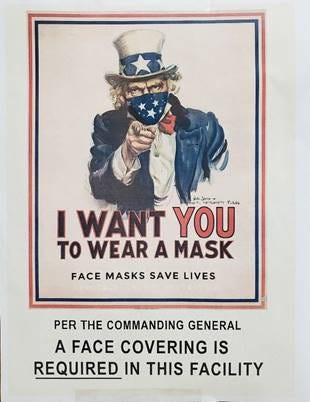

Posters went up immediately featuring a masked Uncle Sam, declaring that “face masks save lives,” without a single data point to back the claim. Outdoor social distancing banners were erected across the installation, and hand sanitizer dispensers became as common as flies. A significant percentage of personnel, including uniformed soldiers, were sent home to work—or simply wait for the Army to figure out its next move. But this wasn’t enough. Base commanders felt they had to do more to prove to higher ups just how seriously they took this new supposed existential threat to humanity.

Next, the men running Fort Leavenworth closed side entry and exit gates, forcing all traffic through a single checkpoint—as if funnelling people together would somehow stop the virus. At the base hospital, they shut down two of the three main entrances, forcing everyone through a single door—while still insisting on social distancing. The commissary, Post Exchange, and even the gas station began requiring ID card checks at the door, as if military IDs had some sort of Covid-blocking property for people who had to show the same ID to enter the base. Non-military-affiliated civilians weren’t even allowed on base, yet this policy remained in place.

An Emergency Operations Center was stood up, where officers briefed the base command team on confirmed Covid cases in the state and updates on commissary food stocks—things the command had no control over. People who lived on base were barred from having guests. Base residents were encouraged to report citings of children playing together, neighbors socializing, and guest vehicles showing up to someone else’s home. On Good Friday, during a discussion about Easter services, the garrison commander declared that soldiers better not attend church. So much for defending religious liberty. The unease I felt at that moment made me wonder if patriotic Russian officers felt the same in 1917 as the tide turned in favour of the Bolsheviks.

Then came Operation Warp Speed, which delivered an experimental gene therapy to be mass tested on military members.

Once the shot was available, Fort Leavenworth’s senior commander, Lt. Gen. Ted Martin, decreed that those who took the voluntary vaccine could live normally—no masks, no restrictions. Those of us who declined the voluntary and experimental shot were required to wear masks—a deliberate move to mark and shame us.

By this point in time I had been reassigned to work as the operations officer for Martin’s public affairs office in the U.S. Army’s Combined Arms Center. My new boss, Lt. Col. Joshua Camara, had shown little interest in me beyond forcing me out of a job I enjoyed into a role of menial work that he was prohibited from pushing on civilian staffers. One day, he pulled me aside and asked why I was still wearing a mask. Had I just not gotten the second shot yet?

I told him I had elected not to take the vaccine while it was optional. His reaction was unforgettable.

Josh stopped typing, dropped his head into his hands, and muttered, “Chase, Chase, Chase”—his voice dripping with exhaustion and disappointment. Then he launched into a lecture about how safe the shot was and made it clear that he disapproved of my choice. It was obvious that my humanity didn’t matter to him anymore. I was now one of those people.

Meanwhile, the messaging from the military ruler caste was relentless.

General Martin repeatedly assured us that the shot was the key to killing the virus. At the Command and General Staff College, my friends were subjected to a lecture from Army University Director Maj. Gen. Don Hill, who declared that getting vaccinated was a moral imperative. He told a class of roughly 1,000 officers that anyone refusing the shot was essentially walking around with a loaded weapon pointed at their loved ones.

Hill’s slogan for the rest of his tenure? “Vaccinate to Victory.” He even had a logo made.

Military officers who had never spent a minute studying medicine had the arrogance to coerce fellow citizens in uniform into making life-altering decisions—solely to satisfy political directives from on high.

Then came April 21, 2021.

That was the day Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin mandated the Covid-19 vaccine for the entire force. I went to the base hospital to ask what the process for requesting a religious exemption would look like. The nurse was visibly disgusted. No exemptions would be granted, she said. Military physicians were pressured to deny requests. A colleague told me that one doctor on base had approved a small number of exemptions—only to be ordered to rescind them because the command wanted everyone ‘vaccinated,’ no exceptions.

I wrestled with whether to submit a religious accommodation request. Things had become increasingly hostile at headquarters. I desperately needed out. So I called my old boss, hoping he could pull strings to get me reassigned. Then the topic of the shot came up.

“The commander has no patience for people who don’t get vaccinated,” Vic told me.

In an act of desperation, I took the shot. Not because I believed in it. Not because I wanted it. But because I needed to escape.

As it turned out, the shameful actions of commanders at Fort Leavenworth did nothing to stop the virus. Covid managed to sneak in through that single entry gate, visiting military members just as it did civilians off base. Yet that didn’t stop base authorities from thinking themselves wiser than most.

Every single day in the Combined Arms Center Public Affairs Office, I heard some variation of the same self-righteous chorus: “I’m so glad I got my shot so I can be safe.”

The headquarters building had become a temple, and the liturgy was strong. Those in this new faith movement spoke with contempt about the Kansans outside the gates—everyday Americans living their lives without masks, daring to make their own choices. I remember one meeting where two lieutenant colonels openly mocked military family members who refused the shot. These officers suggested that such people like my loved ones should be banned from using base facilities—or even from buying food. I was aghast, but said nothing. Cowardice won in that moment. I regret it. Another moment I regret came months later.

One night, while on overnight watch duty at the garrison headquarters, I received a call from someone with an ancestor buried on base. Every Veterans Day, she—along with a small group of other family members—made a long drive to visit the grave and place decorations. That year, she was calling to ask if she would be allowed on base. I had to tell her no.

She didn’t argue. The person on the other end of the line was kind. But I could feel the disappointment in her voice.

By morning, I regretted following the rules. I wished I could do the call over again—to tell this fellow American that I would find a way to get her on base to honor her ancestor. The military cannot claim to care about families while treating them as outsiders. Free citizens dare not go along with such blatant disregard for liberty again.

Immoral restrictions weren’t limited to Fort Leavenworth.

-At Fort Bragg, the unvaxxed were barred from certain gyms and dining facilities.

-At Fort Riley, unvaccinated temporary personnel were forbidden from buying food.

-At Fort Jackson, my wife and children were not allowed to attend my son’s basic training graduation.

-At Fort Gordon, they were prohibited from visiting him during his advanced training—because our family refused the needle.

Yet somehow, as a public affairs officer, I was expected to tell the public that the Army was a trustworthy institution. It wasn’t. I refused to be its mouthpiece from that day forward.

6. You draw a parallel between the treatment of unvaccinated service members and historical discrimination. Could you elaborate on why you see these situations as comparable?

Marking human beings as lessers—viewing them as animalistic property—is a long-standing and dark tradition. Throughout history, rulers have required physical markings to identify those they hold in low esteem. Slaves were tattooed in ancient Rome. In Egypt, they were branded. That practice endured in America until slavery was abolished. More recently, the Nazi regime forced Jews to wear the Star of David. There are many other such civilizational examples.

Human behavior does not change. Creature comforts and technology evolve, but we remain capable of the same savagery as our ancestors.

Ted Martin was not the only senior military official to resurrect this practice. By requiring those who declined the Covid-19 shot to wear masks while the vaccinated walked freely, he directed the ritual of public shaming of fellow American citizens. Elsewhere, it was worse. Colleagues told me of bases where the so-called unvaccinated were required to wear armbands as visible symbols of their defiance. Soldiers on Fort Leavenworth who applied for religious exemptions were forced to undergo weekly virus testing—a requirement I had never seen imposed for any other overdue vaccination. The intent was clear: humiliate, denigrate and dehumanize.

History has shown what happens when a group is singled out in this way. The rhetoric of hatred against those of us who were suspicious of the experimental shot intensified alongside these measures. Many influential Americans called for people like us to be denied medical care, fired from our jobs, and banned from public gatherings. That hatred has lessened, but has not disappeared.

Just last month Cincinnati Children’s Hospital refused to put Vice President J.D. Vance’s 12-year-old cousin on a heart transplant list because she has not taken the shot. The contempt still remains among many across this nation.

The words “Land of the free, and the home of the brave” matter little when the worth of a person is determined by whether they submitted to a government decree. When a society embraces shame, hatred, and isolation against those who exercise bodily autonomy—we enter a dangerous place.

Germany has declared Nie Wieder—Never Again—to the horrors of the Holocaust.

America must also say “Never Again” to shaming, hating, isolating, and believing worthy of death those who hold to their God-given right of bodily autonomy.

7. As someone who served as Director of Press Engagement during what's described as "the worst recruiting crisis of the all-volunteer force," what factors do you believe contributed to this situation?

The Army officially missed its recruiting goal by 25% in 2022, a 15,000 soldier shortfall. In reality, the deficit was 40%. Army officials quietly lowered the recruiting target as the fiscal year’s end approached to soften the public relations fallout. Recruiting struggles continued until this year, when a new administration, a new Secretary of Defense, and a shift from social justice to combat readiness pushed the Army to a 15-year recruiting high.

Could political factors have negatively impacted patriotic young people and their families’ willingness to enlist? According to official talking points: no. But the numbers tell a different story.

I grant that the recruiting crisis was complex. The military once held a monopoly on educational benefits like the GI Bill and tuition assistance, but private companies now offer similar perks. A post-Covid labor shortage also intensified competition for talent. Meanwhile, the shrinking pool of eligible recruits faced increasing barriers—rising obesity rates, prescription dependencies, declining academic achievement via corrupt public schools, and a growing preference for individualism over service. Those are all legitimate factors that complicated the Army’s recruiting efforts. But national politics of the moment proved the biggest problem.

Lloyd Austin’s first act as Biden’s defense secretary was to brand the military an institution plagued by extremists. That sent a chilling message to patriots in the ranks. Who wants to risk dying in a military that hates them? Then came the disastrous Afghanistan withdrawal. Two decades of sacrifice were erased in a week and 13 more Americans died in the final days of retreat. Who would risk their life for a cause that leadership could abandon at a moment’s notice?

Add to that the left-wing social engineering of the force at all levels and the draconian Covid mandates. The cumulative effect resulted in the steepest decline of trust in the U.S. military since Vietnam.

Even more shocking was the dismissal of veteran sentiment. For generations, veterans have been the military’s best recruiters—mentors who inspire sons and daughters to carry on the family tradition of service. But Biden’s Secretary of the Army, Christine Wormuth, called generational service a problem because it didn’t make the Army “look like America.” She never seemed short of motivation to alienate veteran families. By the end of her tenure, surveys showed that only one-third of veterans recommended military service.

As part of Wormuth’s effort to reshape the Army’s demographics, she deprioritized recruitment in the South—historically the strongest source of enlistments—and focused efforts on blue states. It turned out in communities where critical theories take precedent in local culture, young people did not show up in masse to enlist.

During my time as the Press Engagement Officer for U.S. Army Recruiting Command, I repeatedly argued that we should acknowledge the political factor. Denying what everyone could see only made us look foolish. My superiors agreed but insisted we could not admit the obvious because it could be embarrassing to higher levels in government. Optics were what mattered, not truth.

Now, after three years of the worst recruiting crisis since the start of the all-volunteer force in 1973, the Army has rebounded to a 15-year high—immediately following the last election. Those who deny the political element of the recruiting shortfall cannot be taken seriously.

8. Your experience spans multiple military leadership roles. How did the Covid-19 period differ from other challenging times in your career?

For most of my career, the best and worst experiences were shaped by local leadership. On three separate occasions, I nearly left the Army because of toxic superiors—men who thrived in the system by burning subordinates to the ground, meeting metrics, and securing promotions. Their brand of leadership was part of a broader reality in today’s Army. Despite that dysfunction, I held firm to a belief in the institution itself. Each time I considered leaving military service, a change of command restored my faith. I told myself that while some leaders were bad actors, the Army as a whole was still good. The Covid, the Army’s accusations of rampant extremism in the ranks, and contempt shown toward Christians in the force shattered that belief.

For the first time, every officer in my chain of command, without exception, fell in line with the official narrative. Those who privately shared my concerns would only voice them in whispers. Not a single officer above the rank of lieutenant colonel spoke out in defense of basic truth. The colonels and generals—the ones with the least to lose—remained silent, leaving those of us with everything on the line to fight alone. It became clear that the higher ranks were occupied by the kind whom C.S. Lewis described as “men without chests.”

A line from Joseph Heller’s 1961 novel Catch 22 well describes the ethical malleability of such cowards.

“I was a fascist when Mussolini was on top & I am an anti-fascist since he was deposed. I was fanatically pro German when the Germans were here to protect us against the Americans & now that the Americans are here to protect us against the Germans, I am fanatically pro-American.”

In 2020, I realized the Army was no longer a good institution. Then I started reading history—and saw that it ceded the moral high ground at many points in American history.

The U.S. Army has done tremendous good at many points in its history. But it has also at times been the willing instrument of oppression. The rounding up of Japanese-Americans during World War II? An Army operation. Many Army bases sit on land seized from multi-generational communities through eminent domain. During the Civil War, the Army illegally arrested journalists and lawmakers at the direction of political masters. The list goes on. History makes one thing clear: military forces, in every time and place, ultimately serve those who pay them.

Now, with a new administration in office, the generals have suddenly rediscovered basic truths—that there are only two genders and that combat readiness (not diversity initiatives) is the military’s purpose. But make no mistake—these officials have no moral grounding. Left in uniform, they would turn on a dime and do the bidding of Stalin if so ordered by a subsequent president.

9. In your story, you mention that military claims of being 'apolitical' were "laid bare." What specific events or policies led you to this conclusion?

Early in my military career, there was an understanding that military members should avoid discussing issues related to domestic politics while on duty. Official regulations didn’t prohibit such discussions, but the culture strongly discouraged them. That said, I wasn’t a stranger to political debates with peers who cared deeply about the policies impacting our country. We would sometimes engage in thoughtful conversations, always respectful and mindful of the fact that, regardless of our personal politics, we carried out the orders of the President whether or not we voted for him.

But in the final years of my career, it became clear that the military leadership cared far more about serving a particular ideology than fulfilling its Constitutional duty to protect the nation. One particular moment in 2017 demonstrated that to me. I was standing on the Eisenhower metro platform in Alexandria, VA, on my way to the Pentagon when news broke that President Trump had issued a directive to bar individuals who identify as ‘transgender’ from joining the military. This directive was in line with the entirety of human military tradition, a tradition interrupted by former President Obama as part of his use of the military as a vehicle for the “fundamental transformation of the United States of America.”

What shocked me wasn’t the directive itself, but the response from Pentagon officials. They publicly resisted Trump’s directive, virtue-signaling their commitment to the Constitution, while making clear their refusal to follow presidential orders. This defiance made clear to me that the military wasn’t just following the orders of the elected leadership anymore, nor was it interested in the Constitutional text—which says nothing about gender ideology. The brass was taking sides in a heated matter of domestic policy debate. It was not at all uncommon to hear military officials talk about some nebulous ethics of principled disobedience under the first Trump term. That never came up during Biden’s presidency. Over time, the military’s partisan shift became even more pronounced. It wasn’t about upholding the oath anymore—it was about shaping the force according to ideological preferences.

In 2018 I noticed a change.

When I began the public relations program at Georgetown University, one of the things asked of students in the program was their Twitter (now X) handles. It seemed that meant I should have one. Upon joining the platform, I quickly discovered a large group of left-leaning military officers who colloquially referred to themselves as #miltwitter. Its participants spanned from mid-ranking non-commissioned officers to 4-star generals. The culture within this confederacy of social media users was very left of center and trended predatory toward anyone who held traditional views on anthropology and theology. I observed in that mix senior military leaders using their platforms to amplify progressive military-affiliated voices, while diminishing those who did not align with these views.

With Donald Trump being the military commander-in-chief, military members were pressured by military superiors not to voice approval of policies emanating from the White House. The situation worsened during the Biden administration. Service members with conservative convictions found themselves silenced, while those who adhered to left-wing ideologies were elevated as role models and encouraged to share their ‘authentic truth.’ When I entered military service in 2003, no one would have batted an eye if I said there are only two genders. But by 2021, expressing such a belief in the wrong company could lead to disciplinary action.

During this period, I was also a doctoral student at Kansas State University. The modern academy is known for leaning left, and K-State was no exception. Yet, I was surprised to find that the university was more welcoming to my conservative views than the Army had been in my final years of service. The military’s rhetoric about treating others with dignity was very one-sided. The creeds of brotherhood had been exposed as hollow, as the progressive march through the institutions steadily took over the defense department from top to bottom.

10. How did your background in communication and public affairs influence your perspective on the military's handling of COVID-19 policies?

The most fundamental philosophy of being a military public affairs officer is to tell the truth—an extension of the basic honor code that all service members are expected to uphold. However, I learned early in my career that fidelity to the truth was often dependent on one’s organization and chain of command. Some commanders value transparency and truthfulness, but most do not. Unfortunately, those who rise to become the highest-ranking PAOs usually do so by prioritizing institutional protection over their obligations to military regulations and even the oaths they swore to uphold the Constitution.

It became clear early on that little was understood about Covid beyond the fact that it is a respiratory virus. Yet, the military quickly adopted measures like social distancing and masking. Commanders weren’t interested in proof, which was shocking to me. In military planning, commanders typically demand facts. They are comfortable making assumptions when facts aren’t available, but they usually don’t rely on information that is entirely fabricated. With Covid, however, that approach was reversed. Commanders dismissed factual scientific data and instead yielded to political directives.

As a public affairs officer, I observed my peers across the force amplifying messages that masks and experimental shots could stop the virus. Even as it became clear that these claims were demonstrably false, commanders and military communicators continued to push them. Data contradicting the party-approved script was dismissed as “disinformation."

Believing that PAOs had a responsibility to be honest and serve as the moral conscience of the military, I saw the clear course of action: Admit what we knew, and what we didn’t know. Refuse to spread false information. Stand firm and tell rogue commanders that we would not break military regulations to appease them. I believed the best way to serve the military community was through honesty, not propaganda. Unfortunately, every single military PAO who spoke about Covid on the record chose the latter. It was a shameful era in military public affairs practice.

11. You mention that legislative phone lines didn't fill up with Americans calling about troop treatment. What response did you hope to see from the public?

In addition to those who dismissed our concerns with the “you knew what you signed up for” quip, there were others who expressed sympathy. They would say things like, "It's so terrible the way the military is treating you." But not a single one of them took any real action. No one called a congressman, wrote an editorial, or called into a talk radio program to plead our cause. When the generals who had betrayed us showed up at sporting events, they were applauded as supposed patriots—not booed as the oath breakers they are.

When military members are mistreated by the chain of command, the options for recourse are extremely limited. It’s a betrayal of fellow citizens when the public merely looks the other way and offers empty statements of sympathy. I wanted to see the public raise some hell—call out senior military commanders and the lawmakers who fund them. But for that to happen, the public would need to care enough about the military and its members to do more than just offer platitudes like "Thanks for your service." After 9/11, George W. Bush sent America’s military men and women to war. He told the public to go to the mall. Cognitively, the nation remains there despite two decades of sending its sons and daughters into combat.

12. What impact did your experiences during this period have on your decision to retire as a Major (Promotable) rather than accept promotion to Lieutenant Colonel?

My role was that of a military communicator and spokesman. Starting in 2020, I witnessed the Army embrace falsehoods and outright lies as a daily routine. Even as vaccinated people tested positive for Covid, the Army’s narrative remained that the shot would stop the virus. Despite scientific studies showing the futility of cloth masks in preventing the spread of respiratory viruses, the masks save lives deception persisted as an official talking point across the force. Lloyd Austin remained resolute in claiming the military was full of extremists, even as the investigation he ordered came up nearly empty. We were repeatedly told that ‘diversity’ was the military’s greatest strength, not combat readiness, discipline, or a $700 billion defense budget.

I also learned, through personal hardship, that there was no room for moral conscience when it came to promoting the transgender agenda within the force. As a public affairs officer, I was expected to parrot every lie—using my voice, my face, my name, and my creative abilities. In 1977, the famed novelist and Russian Gulag survivor, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, admonished us not to be conduits for falsehood:

“Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, let it even triumph. But not through me.”

His words have been a part of my moral compass for years. I refused to participate in the Army’s lies and faced years of ostracism and discrimination within the Army’s public affairs field as a result. The service had gone from one I proudly represented to one I could no longer affiliate with and keep my integrity.

I applied for retirement on October 1st, 2022. We learned the following April that I had been selected for promotion. It was a bittersweet moment. I wrestled with whether to withdraw the retirement paperwork for a matter of seconds and remained resolved to leave the Army and regain my citizenship. Many thought my decision to forgo the promotion was unwise. But we were convinced that I can serve the cause of freedom far better as a civilian, free of the weight and entanglement that comes from being a military public affairs officer. It is a decision I remain at peace with.

13. You write about Americans' attitudes toward soldiers throughout history. How has your view of civilian-military relationships evolved over your career?

I appreciate the way you phrase that question. Civil-military relations didn’t change over the 20 years I served, but my perspective on the dynamic shifted dramatically. I believed early on that most Americans genuinely appreciate, support, and care about America’s military men and women. This is something we shouldn’t take for granted, especially considering how Vietnam-era troops were treated. Now, however, I think people feel a social obligation to signal support for the troops. They go through the motions but don’t internalize the sentiment as something to truly embrace.

My friend and mentor U.S. Army Lt. Col. (Ret.) Alan Brown poetically summed it up the “thanks for your service” mantra, calling it:

A disposable cliché to quickly discard the guilt you feel for the sacrifices we swore to make on your behalf.

The feel-good line masks your discomfort for what I do, what I have done, for what I could be called to do.

To be clear, no one owes me anything for having served in the military. I volunteered. It took a lot from me and my family, but it also gave a lot. I’m grateful for how being a soldier shaped me, through both high and low moments. My contention lies with people who deceive themselves by saying they care about the troops and veterans, but truly don’t.

We’re not heroes. My generation of troops didn’t protect the nation from totalitarianism during the Covid era. The majority of military deployments in recent decades had nothing to do with keeping America free. The reality is that the troops today are treated like pawns on a game board, as Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler warned in his 1935 book War is a Racket. Despite this, most of us still want to protect freedom. But it’s an open question whether our military men and women will be allowed to. Seeing military units recently deployed to the southern border, rather than to some far-off nation, gives me a glimmer of hope that perhaps the Defense Department will refocus on protecting Americans, rather than propping up or tearing down governments abroad.

14. You've written about military members being viewed as "lesser citizens." How do you think this perception could be changed?

Soldiers have often been looked down upon by the general populace throughout history. Early Americans saw standing armies as a threat to liberty, and one of the fundamental protections of the U.S. Constitution was the prohibition against forcibly quartering troops in private homes. That underlying desire to maintain distance between civilians and the military still exists today, masked by social conventions that require public displays of appreciation for service members at parades and sporting events. Societal perceptions about military members may never fully change—but what can and must change is how the legal and civic rights of military personnel are respected.

This shift must start within the military itself. First, lawmakers must hold commanders accountable when they restrict their subordinates’ rights beyond what law and regulation allow. Second, the Department of Defense Inspector General must be moved outside the chain of command. Allowing the military to investigate itself guarantees a total lack of accountability. Third, the nation needs a revival of civics education—one that reinforces the fact that America’s military is not a separate caste but a force made up of citizen-soldiers who retain their civic equality even while in uniform.

America’s military was never meant to be a mercenary force for foreign adventurism, detached from society. It was originally envisioned as a locally based, well-trained and regulated militia that could be called upon in times of war to defend the homeland. A return to that model—focusing on a smaller full-time force complemented by a stronger, more widespread part-time reserve—would better serve both national defense and the relationship between the military and the public. When troops live, work, and worship in their hometown communities, it becomes far harder for commanders to mistreat them and far easier for civilians to see them as equals. In that Constitutional model of military structure, the public would know their soldiers because they would do life together.

It’s long past time to tear down the walls the Defense Department has erected between the military and the American people. We are all Americans—and should act accordingly.

15. You've founded a leadership practice focused on coaching principled leaders to "find their spines" and "lead boldly" - what inspired this direction based on your military experiences, and how can people engage with your work to create positive change?

The military is full of creeds about courage, but I learned that physical courage is entirely different from moral courage. There are many among our military warriors who would charge into gunfire or throw themselves on a grenade to save their comrades. Yet, the number willing to speak even the most basic truths in the face of compromised and corrupt power is infinitesimal. We must turn that around.

Over the past few years, many have reached out—some who witnessed my actions firsthand, others who read my work—to express appreciation for my willingness to speak up. Almost always, they add the same caveat: I wish I could, but I can’t. Early on, I sympathized. Taking a stand isn’t easy. It is burdensome and comes at a cost. But with practice, standing firm becomes less difficult. These days my patience wears increasingly thin for those who admire from the sidelines and hide in the shadows, but refuse to act.

One of the predominant reasons I left the Army in 2023 was to be free to serve in a more meaningful way. Last year, I launched a practice dedicated to coaching, advising, and encouraging those who share my moral convictions—helping them turn those beliefs into action. My goal is to use business and writing to embolden others, equipping them to lead with integrity and conviction in both their personal and professional lives.

This next chapter of my life is about preparing leaders of moral courage to awaken it in themselves and inspire it in others to embrace Winston Churchill’s proverb that Courage is Contagious.

If that resonates with you, I invite you to visit chasespears.com to learn more and connect.

I appreciate you being here.

If you've found the content interesting, useful and maybe even helpful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While everything here is free, your paid subscription is important as it helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. It also helps keep it free for those that cannot afford to pay.

Please make full use of the Free Libraries.

Unbekoming Interview Library: Great interviews across a spectrum of important topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Concise summaries of important books.

Stories

I'm always in search of good stories, people with valuable expertise and helpful books. Please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com

For COVID vaccine injury

Consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Baseline Human Health

Watch and share this profound 21-minute video to understand and appreciate what health looks like without vaccination.

I've only in the last year come to the realization that in being a "good" conservative, believing in democracy building, and all the other policies, whether Neo-Con, War-Hawk or Zionist, it's no better than the Left side of the isle. We are being pushed onto the same road at the fork. None of it has anything to do with the USA or the American People and our sovereignty. It's all power and money and always has been, with controllers that care absolutely nothing about the population, neither civilian or military personnel.

I used to be one of those who would "Thank" Veterans for their service, and I began to feel guilty about it wondering how I could express what I was feeling to them. I've donated to Veterans organizations to try and help, but no longer publicly say "Thank you".

We can't blame our soldiers for taking a vaccine when mandated to do so. Why would they be any different than the majority of the population that lined up for the first 2 jabs? And they were under great pressure to do so because they've been conditioned to obey orders and feel they have no choice. I knew people who drove hours away for the shot because they knew they could get it faster. My husband and I were self-employed so had an easier time rejecting the mandates, not everyone had that luxury.

Chase, I hope you know that there are many people who support and have sympathy for the sacrifices our military make. My sympathy has changed though and beyond loss of life, disability, and separation from family, it extends to, they DO NOT know what they've signed up for, through no fault of their own. Most are young and haven't experienced enough of life to even form an opinion. Some sign up for economic reasons, but many sign up with very noble intentions. Noble intentions are not what the government uses the military for.

The general population is under a spell and that includes military personnel, they've been duped about all of our "magnificent" institutions, Technology to control us, Education to dumb us down, Food to make us sick, Medical to kill us and yes, our Military to "keep us safe". A digital monetary system with ID will be the frosting on the cake. How will they enforce it?

It is beyond depressing when you learn just how few soldiers actually refused the jab. Some lessons are simply too important to learn the hard way, like playing on the 405 freeway.