“There are no weaknesses in the theory of evolution.” Eugenie Scott, spokeswoman for the National Center for Science Education.

Rarely has there been such a great disparity between the popular perception of a theory and its actual standing in the relevant peer-reviewed scientific literature. – Stephen Meyer

Darwinism was nearly dead by the early 20th Century. It's not a science, it's an anti-religion. – Liam Scheff

Discovery is seeing what everyone else saw and thinking what no one thought. - Albert von Szent-Györgyi

The teacher arrives when the student is ready.

Ok, this subject matter is a bit different…but not really.

Every big stone I look under, I find the same thing, something hissing, corrupted, dogmatic and captured, whether by ideology, industry or careerism. Something angry at having lost the comfort of darkness.

In 1992, while 23, a wonderful man tried to explain to me that atoms cannot find their way to parts that cannot find their way to a working watch, no matter how much time elapses. What he was trying and failing to do was explain “intelligence” and “intervention” in the “design”, with a bit of “irreducible complexity” thrown in for good measure. He was a religious man, so I didn’t consider he had anything useful to say on the matter. I dismissed him.

The student wasn’t ready…

The old me loved The West Wing. The new me doesn’t mind it, but I see it very differently now. I know that much of it is not functionally true. It’s a fairy tale of sorts, and who doesn’t like a good fairy tale.

Politics is downstream from culture, which is downstream from education and entertainment. Entertainment is more widely consumed, more invisible in its effect, more insidious. So, politics is downstream from entertainment.

The best propaganda is when you don’t know it’s propaganda.

I remember watching the clip above, it must have been 2005, and I remember thinking that it was absolutely right. Intelligent design (ID) in schools, definitely not!! I believed that ID was just a clever way of smuggling religion into schools. Darwinian evolution theory was an asked and answered question after all.

There’s a moment where he, Matt Santos, says, “intelligent design is not a scientific theory, it’s a religious belief”. The 2005 version of me couldn’t agree more.

In that moment, it’s as if an invisible had entered my head and flicked a switch to “off” that shut me down to considering anything about this idea of intelligent design. It’s a religion after all…Matt Santos told me.

Again, the student wasn’t ready…

Well, well, well…here we are today, with a GMC under my belt, and by the end of this piece you are invited to reflect on the Santos line and ask yourself, which one of the two ideas in question are more dogmatic and less scientific than the other. Which one of the ideas better explains the origin of life, Darwin’s evolutionary randomness or intelligence in the design.

Which one of the two ideas is truer or likely truer. Which is more scientific, in the true sense of the word.

The reason I wanted to write about this is because my awakening to the subject is brand knew. As I meander through the rabbit warren, I discover, often by accident, new chambers (new big stones to look under). I have always been reasonably curious, and if I didn’t know about the existence of this chamber until now (53 yo) then I suspect most people don’t know either. So, this article is an arrow, pointing the curious, to a new, and I think truer way of seeing the world. Science is just the search for truth. The Science™, well that’s something else entirely.

The teacher arrives when the student is ready, and in my case, I’m ready, and the teacher is Liam Scheff.

I’ve mentioned Liam Scheff and Official Stories before. We lost Liam way too soon. As I get to know him a bit through his writings, I’m not sure I’ve come across anyone else like him. As Levi Quackenboss recently said:

You can help support the loved ones that this brilliant mind left behind by purchasing his book, Official Stories. In case you haven’t noticed, there has never been a replacement for Liam. He was truly one of a kind.

To anyone that would listen I’ve said that The Real Anthony Fauci was the most important and impactful book I have ever read, followed closely by Inventing the AIDS virus and Dissolving Illusions. Each of these books is a monster in terms of their sheer size and volume of knowledge and research that has been packed into them.

With that said, Official Stories, is a short book with 11 short chapters, and to my knowledge the only non-fiction book Liam wrote, and in my opinion, it sits above the three books mentioned above. Each one of those three books goes deep into a rabbit hole, while Official Stories is actually describing the warren. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

The first chapter I read was chapter 5, on vaccination, I wanted to see what Liam’s world view was on vaccination, and he was spot on. You can see the years of research that he has gone in those 20 pages. Then I started reading the book from the beginning and at one point looked at the table of contents to see what subjects were coming up, and there was chapter 8, titled Darwin is Dead.

I stared at that title with dread.

I had two competing thoughts. The first was that surely Liam is not going to dismantle evolution, and the second and more likely dread was that I was terrified Liam’s credibility and standing would come crashing against the absolutely rock-solid science of evolutionary theory.

And so, with that dread, I started reading…

I then went looking for other material that might help me understand Liam’s chapter and came across Stephen Meyer and Michael Behe. I’ve now watched quite a few of their lectures and what I would ask you to do first is read Liam Scheff’s chapter below, and then come back and watch this Meyer lecture, and then go back to the bottom and read the Prologue from Meyer’s book, Darwin’s Doubt and excerpts from Michael Behe’s book Darwin’s Black Box.

If at the end of this you, like me, come to see and think about evolution, randomness, intelligence and design differently, and if you see the stifling, suffocating religiously academic dogma that I now see, let me know.

The problem with The Science, and frankly with the rationalist, mechanistic, supposedly “atheist” Western mind is that it doesn’t deal well with not knowing.

We know it doesn’t deal well with being wrong, and definitely doesn’t deal well with narrative that challenges industrially captured science, but what is less obvious is how unwell it deals with not knowing. This discussion of “intelligence” does exactly that, it drags The Science to a place it’s terrified of a place without obvious answers of who, what, where when and how. For many this is a religious place, and frankly that is perfectly fine by me, it’s actually a far more legitimate posture than I once thought it was.

But this is also a scientific place, if by “science” we simply mean truth, or the enquiring process that seeks it out. Science can arrive at a place, and honestly throw its hands up in the air and say, “I don’t know the answer, and I might never know”, while The Science will kill you before you get there.

Anyway, this has been a very interesting journey for me, and I wanted to capture some of my thoughts while it was still fresh. Hopefully it sparks something in you too…

With thanks to Liam Scheff, Stephen Meyer and Michael Behe.

Liam Scheff

Chapter 8: Darwin is Dead

The Official Story: The Darwinian theory of evolution. It says that over long periods of time and through slight, accidental, successive changes, species make radical alterations, moving from earthworms to elephants, because of competition and natural selection - because the “fit” in the group “survive.”

The Lone Gunman: Nature.

The Magic Bullet: “Random chance” over time. And lots of it.

Darwinism. It's been the guiding philosophy of the 20th Century. It reformed science, rescued it from the fog of religious dogma and brought us into modernity. At least, that's the advertisement. But Darwinism, the scientific theory, hasn't fared so well. Its failures are most often hidden from the public, but the theory has so been bloodied and beaten by pointed criticism from both insiders and outside critics, that it’s been significantly abandoned as a research tool. But they haven't changed the textbooks yet to catch up with what's happening in research. So, consider this a rude, late awakening, from a philosophy which has done as much or more to damage the mind of the world, than any misbegotten religious dogma.

Or, let me back off a little and get back to Charles.

Scratch 1:Charles Darwin was a naturalist in an era when scientists were called “natural philosophers,” and not “scientists.” Natural philosopher. It carries the feeling of openness, thoughtfulness, a desire to watch and learn. Scientist. It’s a more aloof, isolated and authoritative title. It is a club that you probably don't belong to, but one whose pronouncements you are expected to believe. And which you may be compelled to comply with.

Darwin was a naturalist, not a scientist. He wasn't much of a philosopher, but we’ll get to that.

He did take a trip on a boat, or several. He visited the Pacific Galapagos Islands, where he he observed a variety of wildlife. He noticed that the island finches were all similar, but also possessed slight differences. He decided that they had changed over time because of competition, which cemented changes that he felt occurred by random, accidental chance. Competition and accident were the drivers of his model.

He wrote a book to promote his idea called “On The Origin Of Species, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.”

From the title, you'd expect such a book to tell you “the origin of species.” That is, where life comes from. But it doesn't. It doesn't even try. “Life exists” is the first given in Darwin's book.

So, the book is misnamed. It could have been called, “How Life Forms Change Over Time, In My Opinion,” by Charles Darwin and been off to a better start. But he didn't. Which didn't matter to anyone who read it. Because his book wasn't really about evolution. It was about religion.

The purpose of Darwin's book and the entire “scientific” project of evolutionary theory, was to destroy a different model of life, the prevailing model of creation: the Christian “Yahweh-driven” model, otherwise known as “Genesis.” But I'll explain what I mean.

The Same Old Situation

Natural philosophers of the 18th century faced a particular problem: the church and its progeny philosophy, that God created all things and that things are now as they always have been. This has been the view of most of Western history. It's called “uniformitarianism,” and we'll see it again in the next two chapters. The philosophy goes like this:

“Things have always been this way. The Earth was made this way. All the animals that have ever lived are still alive. The mountain over there was always there, too. Sure, people come and go, but people have always been here, after the Christian God made them.”

But during the early 1800s, new discoveries were conspiring against the uniformitarian worldview. There were fossils of fish on mountaintops, ancient tree remains in frozen tundra and on every continent, bones of animals that no one had ever seen. It dawned on the natural philosophers that the world had indeed changed. But how much?

This is a difficult question to consider deeply. If life has changed radically, it means that everything is impermanent. Everything you have, you will lose. Everything you love will disappear. This type of thinking makes most people anxious. A universe callously destroying everything it makes, all that we love and become attached to, is a heartless bastard to our sensibilities. No wonder we love stories with happy endings. If you only believe in the visible, empirical world, the calamitous nature of things can rend one proximally insane. Even with a spiritual view, life is hard.

According to former Harvard paleontologist Gould, life’s evolution, despite the connotation of the word, is not an ever-increasing, progressive rise in complexity but a meandering and directionless path marked by myriad “contingencies” and mishaps, such as mass extinctions. If we took Earth back to the beginnings of life and let the evolutionary process play itself out again, life would take on completely different forms from those it took on during the first go round. Darwin’s central message, Gould contended, is not one of progress, in which we are the crowning achievement of either creation by divine fiat or a progressive evolutionary process, but purposelessness. In short, according to Gould, the Darwinian revolution bears the same basic message as the Copernican Principle: We’re not special.

The Privileged Planet – Guillermo Gonzalez and Jay W. Richards

The reason I'm talking about spirituality in the Darwin chapter is because the sciences, from vaccination, to evolution, to Big Bang astronomy all ride on ancient psychological and religious undercurrents. Science hasn’t replaced religion so much as it’s set itself down in religion's deep footprints. But let’s test this notion.

Vaccination perfectly recapitulates baptism. It is a strange blood ceremony performed on infants and children. It is seen as a right-of-passage. Its defenders act with religious zeal, persecuting those who dissent from the ritual as heretics, just as the Church once punished “witches” by forcibly managing their lives or ending them.

HIV theory recapitulates lost tribal and cultural sexual boundaries and rituals, which were washed away in a sea of pharmaceutical “freedom” and over-liberated libido. Where we used to have Commandments and Leviticus, we now have the “HIV confessional” (see the previous chapter).

Darwinism recapitulates a concept of meaning. It asks, “How did we get here? Where did we come from?” This is a profound question. To answer it, we're supposed to turn to “evolution.” (We'll get to the religious subtext of “Big Bang” theory in the next chapter.)

For true Biblical literalists, those who reject all information but that translated from politically-adjusted books compiled by committees 17 centuries ago, no technical argument is too vast to hurdle by a profession of faith. It all comes down to belief. Faced with ancient bones, ardent fundamentalists will argue that the Christian God was tricky and planted fossils here or there to test our faith. “There were no dinosaurs! The bones are a trap! Do not be deceived!”

But it's an annoying argument, because it's a kid's excuse. It feels like a joke we tell to get out of a jam. “No, it wasn't me who ate that ice cream. We must have raccoons in the fridge.” Most of us don't think God is such a childish brat, so we don't tend to accept this “God is tricking us” kind of thinking.

Most of our religious texts are politicized translations or mistranslations of very old books. Having “faith” in them is like having faith in a freeze-frame of a 2,000-year-old game of “telephone.” If my motto is “think for yourself and never stop learning,” then I can't be satisfied with being a Biblical literalist.

Chance

The natural philosophers were looking for a way to get out of that trap. They tried to describe the natural world, but very early in the game they developed a religion of their own. It can be described in a number of ways. The shortest is this: “There is no God.” This became a popular philosophy among intellectuals in the 20th Century. As the machine age dawned and we controlled the flow of water, food and resources with greater dexterity, belief in our own wonderful inventiveness surpassed the worship of Old Testament thunder gods. Among intellectuals, the notion that “God is dead” became a daring, cutting-edge declaration of mental freedom.

But what did they really know? It's not like they were involved in comparative religious studies. They weren't talking about Brahma, Krishna, Buddha or the Tao. They were making a rebellious political statement. They'd had enough of one kind of God. That of the money-grabbing, state-managing churches of Europe and the 700 rules coming out of Leviticus, which seemed to have nothing to do with the increasingly modern world. Darwinism grew up in this climate, as an anti-religion. Not a science, but an oppositional philosophy.

Religion: Life was made by an all-powerful being. It has always been this way.

Darwinism: Life was made by accident, it has changed, also by accident.

The evolutionists were beating back a dogma. It probably needed to be beaten back, to allow intellectual exploration. So, let's get back to Charles and see what he came up with.

Survival of the Fittest

We have grown up with the expression. We use it when we see someone fail at something so miserably, so spectacularly, that we can only acknowledge the triumph of disaster. It is the phrase that college boys use to mock a fraternity brother who falls down the stairs drunk, or leaps off a hotel balcony into a pool below, hitting the diving board on the way down, breaking some number of bones in the process, having consumed more alcohol than is almost physically possible.

“Survival of the fittest!” The phrase is now commonplace. It has been employed in schoolyards, by scientists and leaders of nations alike. Its philosophy has been embraced by the likes of Mao Tse Tung, Joseph Stalin and Adolph Hitler. Which should bother people, but doesn't. So, what does it mean?

Darwin saw that the island finches were different, slightly. Some had longer beaks, some shorter. Some birds were a little taller, larger or smaller, with a little more or less of a wingspan. Some really hated “Sex and the City” while some found it tolerable, though it really described the lives of the gay men who wrote the show more than actual women in New York. I mean, come on, a new guy every week? That’s boy’s town.

Because Darwin had to exclude the idea that things had always been this way and that these changes had been made by magic, or a god or spirit, he had to come up with a naturalistic explanation. And he tried. He called it “natural selection,” which is pretty tricky. Because it turns the old Christian God into “nature,” and makes you think that it didn't. But almost no one noticed, because they so wanted to get rid of the damned Church, meddling in everybody's bloody business.

I mean, really. Burnings at the stake, witch-huntings, endless taxation. Scandal after scandal with the clergy. Some of the monasteries were more like jelly-making whorehouses than places of reflection and worship. “Screw them,” said the new scientific elite. “We'll support the best contender, even if it is a dog.”

And here it is: “Natural selection” and “survival of the fittest.” Let's unspool it in a little dialog I call, “Define your terms.”

Critical Thinker: What is natural selection?

- Darwin: It is the process by which some are selected for survival.

CT: Who does the selecting?

- Darwin: Nature.

CT: But what is nature?

- All the things that happen in the natural world, that men do not create.

CT: Isn't that a little broad? What things?

- Life, birth, death. All natural processes.

CT: That's a bit circular, isn’t it? So, what is “nature?” How does it work?

- Nature follows natural laws. “The laws of nature.” I'm sure you've heard the expression before.

CT: Sure, I've heard it. But isn't that a little self-defining? Okay, fine, I'll bite. “The laws of nature.” And who upholds the laws?

- Nature does.

CT: But, how? Can you go to jail if you break a law of nature? Are there “nature police” to keep you in line, if you try to get around, say, gravity?

- Don't be ridiculous! You can't break a law of nature. They're immutable. It's just the way things are.

CT: You mean, there are patterns and forces in place that are constant. You don't know how or why. And you don't call that a supernatural force? You're saying that life exists and so do planets and galaxies. You call all of it “nature.” You then deny its intelligence, or will. You then label it “accidental,” despite it being in every part, impeccably ordered and wildly creative? And you call this “random chance?”

I have discovered that this line of inquiry quickly makes Darwinists fume and either curse you out for “misrepresenting their ideas,” or turn away in angry silence.

But it's a fair question. What is this thing they call “Nature?” As Darwinists use it, it's a stand-in for “undefined cosmic intelligence,” and because it's not spelled G-O-D, Darwin got away with it. But don't say this to Darwinists, they'll hiss and cry like intemperate foxes. But more on that later.

Good Breeding

In Darwinism, “nature” “selects” those who are “fit.” And so the “fit survive.” Which brings us to the famous phrase. Darwin didn't pen the expression, his cousin did, but it stuck and soon Darwin was using it too. And “Survival of the fittest” became the catch-phrase of two world wars and the 20th Century.

Darwin said that competition among members of a species winnowed out those who were not “fit,” and allowed the “fittest” to, yes, “survive.” The next generations, therefore, looked more like the “fit” than the “unfit.”

And, man, did this idea take off. So much so that an entire science of “fitness” boomed in the early 20th Century right here in the United States. “Eu” (good) “genics” (breeding) was the name of the game. Eugenics. The science of good breeding - and everyone wanted you to be into it.

Margaret Sanger, who founded Planned Parenthood, was deeply in favor of the reproductive rights of those most “fit” people to procreate. And very opposed to the baby-making of the “unfit.” She wanted them to be assigned to “concentration” camps, where they would be sterilized and freed from the terrible burden of their unfitness.

She also called them “feeble-minded, imbeciles, morons” and “idiots,” too. But remember, these were the scientific terms of the age. You can look it up.

In 1939, Margaret founded the Negro Project and drew in African-American ministers and leaders to spread the gospel of birth control to the masses. Well, the masses of African-Americans, who were, to her way of thinking, over-breeding and probably not “fit.”

But not just African-Americans, also the very poor. It was seen as very important that the very poor also were given all of their rights to be prevented from baby-making, as a matter of “fitness.” As this science grew, doctors and scientists founded centers of research in universities throughout the country, in institutions of advanced medicine, like Stanford, Yale, Harvard and Princeton, with big funding from big names like Carnegie, Rockefeller and Harriman. (Brown Brothers Harriman was a bank that really helped Germany get on its feet in the 30's and 40's - see Chapter 2.)

Even the Supreme Court judge, Oliver Wendell Holmes, was a fan. In 1927, he voted against the right of a young woman named Carrie Buck to make babies. At 17, she had been raped, became pregnant and given birth to a healthy child. Naturally her foster-parents had her committed to an institution for “epileptics and the feeble-minded” because of her “promiscuity.” (The rapist was their nephew, by the way.) The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with their ruling. She was given a surgery to cut and remove her fallopian tubes. Because, said Justice Holmes, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

And maybe it was. Hey, I wasn't there. Certainly Carrie Buck didn't agree and from my admittedly strange quasi-libertarian point of view, I think that really should have mattered more. But, whatever. It was science. And law.

And there's nothing like obeying the law! Thirty-three states ratified the Holmes decision and brought sterilization to their citizens. By 1981, 65,000 people had been sterilized in the U.S. Fitness abounded!

The fashion spread to Europe, where Sweden, Switzerland and even Germany, if you can believe it, embraced the science of “good breeding,” and began forcibly sterilizing the “idiots” who weren't fit, by the tens of thousands. Sweden really got into it, sterilizing 63,000 people, mostly women, by the mid 1970s.

Germany took it even further and had a great time with it. They not only sterilized - they actually went the next logical step and started euthanizing (which is like “putting to sleep,” or “killing”) mental patients and disabled children. Which they kind of did in secret. Which is surprising, because it was scientific and they should have been proud as they were helping the “fit” to “survive.”

But this one bit of shyness didn't prevent them from really taking it all the way and developing a system to just get rid of all the idiots and unfit people all over Europe. The gypsies, homosexuals, artists and protestors and, you know. The Jews. All the Jews they could round up. They brought in millions of them!

And they got IBM to tattoo numbers on people's wrists to keep track of who was unfit and who was to be “put to sleep” (and also cooked, gassed, shot, buried alive, tortured, experimented on, made into soap and lampshades* and buried in mass graves or incinerated). And it was a big success. (*Although the soap and lampshade stories are disputed.)

Problems with Survival of the Fittest

If I am quoted from this book, I hope the reviewer will note that the above passage exhibits a form of extremely bleak humor called “irony.” Because that is what happened. The Holocaust, the most shocking, disgusting, disgraceful, heart-shattering episode of depravity in our collective memory, was a medical and scientific project.

You can squirm and protest and say that they were “perverting the science.” But you'll agree that eugenics was the science of the day and the Holocaust was, in the coldest sense, a logical extension of “fit” and “unfit,” if from an entirely sociopathic point of view. A point of view, however, embedded in Darwin's idiotic philosophy. Because it was never a science.

Accidentally Pink

If a bird is fit, it survives. If it survives, it was fit. But what is fitness? Animals, plants and all life come in so many shapes, sizes and colors, at all levels of land, air and water, from the tiniest bacteria to the largest dinosaurs - and all of this must be attributed to “fitness.”

So, what is it to be fit? Is it to be either: small, fast, large, heavy, slow, bright, dark, beautiful, ugly, florescent, heavy-boned, transparent, microscopic, twenty-ton, hideous, venomous, cuddly, tree-dwelling, night-hunting, root-eating, sand-burrowing, eight-legged, propellor-driven, long-tailed, chitin-wrapped, furry, feathered, scaled, striped, beaked, toothed, multi-organed, single-celled, blind, thousand-eyed, wet, dry, loud or quiet?

“Yes.” Goes the response.

But what is it to be fit? The 2-centimeter red coral seahorse is evidently “fit,” because it exists. But is bright red the color that defines “fitness?” Not for an elephant. Or a zebra. Or oatmeal. Is small the size of “fitness?” Not for a hippo swimming among crocodiles. Or a whale, a pterodactyl or buffalo.

So, what is it to be “fit?” The answer is: there is no answer. It is to be “adapted” to an environment. But adaptation indicates a kind of intelligence and this is strictly forbidden in Darwin's model.

Darwin and his successors' primary motivation was to destroy any notion of a mind at work in the process of life. The process had to be completely mindless, accidental and “random.” It also could only be built in very “slight, successive” changes, which “accidentally” piled up into something like us.

So, why is the 2-cm red seahorse red? “By accident.” Why does the hippo live in water and breathe air? “Random chance.” Why do elephants have trunks, love their young and honor their dead? “Random mutations.” Why do birds have wings? “Cosmic stupidity.” Why don't horses? “Luck of the draw.” Why do a thousand insects, lizards, birds and mammals exactly replicate the color and patterning of the trees, forests, deserts and plains they inhabit? “Dumb luck.” Why do some animals send a cascade of chemicals that instantaneously alter their skin to color-match their changing surroundings? “Blind, stupid, idiotic, moronic, desperate, smelly, feeble-minded random bloody chance.”

Tautology

What is it to be fit? There is no single answer in Darwinism, except, “to survive.” And to “survive?” This is easier. It doesn't actually mean to survive. It means, to hump before you die and to make babies which look like you, or almost like you.

Which means that anything that screws and makes babies is fit and therefore survives. Hooray! And therefore, it should be prevented from breeding, if Margaret Sanger or Judge Holmes say so. Or, well, you get the idea. And you see the problem, or I hope you do. This is not a model on which to base a just, humane or decent society, if we use genocide as a lesson. But is it a model that “nature” uses?

The Engine of Change

Darwin didn't say where life came from. It was just here (so much for overthrowing uniformitarianism). But he said that by “slight, successive changes,” brought about by “competition” between individuals, a bear would one day become a whale.

Yes, he did say that. He speculated that over time, a bear, being exposed to the cold water and swimming, would give birth to children that resembled a whale, more and more, widening the mouth, losing hair, growing, shifting from one kind of food to another and so on.

He even allowed, in an early version of the book, that the environment was a factor which influenced change. But he removed that passage because it was determined by the thinkers of the time (the anti-religious scientists) that the environment could exert no influence on an organism to make it change. It had to be entirely by “chance” that an animal gave birth to sufficiently different offspring, that looked more whale-like and less bear-like. There could be no active feedback loop from the outside, to the inside.

This is the cross that Darwinism pinned itself to and this is where it would die. But we'll get to that.

Thought Experiments

If you ask yourself how a worm becomes anything other than a worm through baby-making, you can imagine a worm giving birth to a worm with little nubs on its sides, and ten generations later, having those nubs elongate slightly, and twenty generations later, form a bend, and 100 generations later, elongate from the bend, and 1,000 generations later, have the bend sprout a nub. And so on, for whatever amount of infinite time you deem necessary for a worm to sprout eyes, a nose, a muscular-skeletal system and the arms and little fingers, legs and toes of an amphibian. Or a mouse, or a bear-whale, or whatever.

And you can imagine this. But what about the insides? What about the process of sight, hearing and touch? Of interlocking cartilage and bone, of biomechanics and the mechanics of chemical interaction? All of these are dependent on inter-locking physiochemical cascading reactions with intricately-formed molecules that work lock-and-key in a truly irreducibly complex system. Lose one molecule in these chains and the thing no longer works.

“And what about it?” Asks the Darwinian. “It all happened by accident. Slow, successive, moronic accident.” And if you believe that, you can close the book and jump in a lake and call me when you manage to breathe through the top of your head, chase zipping fish at high-speed, catch them in your long snout while leaping through hoops at Sea World, because you're a porpoise and why would I argue with a porpoise?

Loose Change

The reality is, Darwin didn't offer any set of variables, no crisis point, no chemical reaction, no mathematical formula for change. There is no science in Darwinism. It's all thought-experiments. You can't do science with it.

Darwin avoided the question posed by the title of his book. What is the origin of species? Of life? It's too big a question to ignore when talking about “evolution,” or change, in the forms of life. What are the microscopic and macroscopic patterns of life and do they point to an idea of what life actually is? It's a massive question. And only a brazen fool would presume to answer it (see Chapter 11).

Bred In The Bone

What is the origin of the change that Darwin says occurs in the progeny of living things? Is it eating a fiber-rich diet? Being kind to children and animals? Following your dreams and learning to water-ski in Boca Raton in a seven man acrobatic team? Will that make the important changes happen?

Deep in “Origin of Species,” Darwin answers the question, “Why do things change?” Things change because, says Charles, they have an “inherent tendency to variability.”

Well, stop the presses. Inherent tendency! Holy. Wow! Glad that's solved, we can end now in peace with no more questions.

But wait. If life has an inherent tendency to manifest in a variety of forms, then “survival of the fittest” has nothing to do with evolution. Life changes because it “has a tendency” to.

If it's “inherent,” it means it's programmed into us. It's inseparable from our nature. Which would indicate to someone who, let's say, builds things or programs computers, that something programmed our nature. Or, that we're a part of something much larger than ourselves that is ordered, structured and, frankly, creative, intelligent and active all the time, in all processes, at all levels of the universe.

And I can't tell you what that is. Personally, I lean East. I like the Tao. I like the Hindu myths. But you'll ring your way.

The Fossil Record

The problem with Darwinism is that there is no math to define when, why, or how evolution happens, or under what pressures and circumstances.

What are the variables that allow these “slight, accidental, successive changes” to bundle a worm into a butterfly? Funny, worms do turn into butterflies - but how does this go along with “slight, successive and random?” It's rapid, shocking and deeply structured.

The fossil record has not been kind to Darwin. The notion of “slight and successive” has had its ass kicked by “explosions” of life embedded in ancient shale. First there is very little and then, all at once - Boom! A variety of organisms that had no visible predecessor. Like a worm into a butterfly.

But I wasn't there, and maybe there are missing bits. On the other hand, maybe life changes wildly because of external influences. This idea, that organisms change pretty quickly, in a response to environmental forces, was a theory during Darwin's time and it had its followers.

The fellow who suggested this model was named Antoine de Lamarck and he has been the butt of jokes in university science departments for 150 years. Until a few minutes ago.

Lamarck

Antoine de Lamarck was a natural philosopher. Like Darwin, he wanted to explain how life variegated - burst into its never-ending melody of form and color.

Antoine did not believe in “random chance” as an engine of the near-infinite variety we see on Earth. He suggested that an animal brought on change through exertion. That a horse-like animal trying to get to the leaves on the top of the tree, stretched and stretched its neck - and grew. Or, that its child would have a longer neck because of mom or dad's exertion. And that its child's child would have a still longer neck and so on, until the horse became a giraffe.

This is fanciful and colorful and playful. And Darwin believed it, for a little while. That's where he got his swimming bear-whale. By constant exposure to an environment, an animal would be altered. But that was abandoned in favor of the “Duh! whoops!” or “slight, successive and accidental” model.

Lamarck suggested that an animal sent “humors” through its blood - some kind of signal, liquid or chemical - to the parts of its body most affected by a task, or a determination to change. And therefore change happened, even during its lifetime, but certainly in its young.

These are just-so stories and they're cute, but life doesn't seem to work precisely this way. Because he was wrong in some ways, he was abandoned (or perhaps he was ridiculed because he gave the universe a will and a mind, and the anti-theists could not tolerate that). For Antoine, life was purposeful and creative. For Darwin and his followers it was accidental, blind and dumb.

As a result, all research into evolution has proceeded, for 150 years, down the path of “blind and stupid.” What if it had looked at “creative and intelligent” instead? Antoine was certainly not correct in many regards, but he got something right and we'll come back to him.

Eugenics 2.0

In the 150 years since Darwin, we've had eugenics, the Holocaust and the revolution in “genetics” which is, by the way, the natural consequence of the “science of good breeding.” Those old eugenics labs in Cold Spring Harbor, at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Stanford and the major institutes of medicine didn't go away, they metamorphosed. They became genetics labs and the UN Population control program, still in operation and still sterilizing women in the “third world.”

Today, we believe that life is determined by genes. And scientists are very busy trying to engineer a better you. So far, they've managed to alter almost the entire world's supply of corn and soy, by mixing those genes with those from other plants, animals and bacteria. As a result, small animals that eat these grains and seeds develop holes in their stomachs, get cancer and lose the ability to procreate within three generations.

By the way, it is our old friend, Monsanto, who gave Agent Orange to Vietnam, who leads the world in this field of genetic modification. The company has bought most of the world's seed supply and is engineering it into oblivion. What can I say? Himmler would be proud. Beaming, even.

Rapid, Non-Random, Non-Successive Change

If it seems too childish and fanciful to suggest that by stretching, you'll have taller children, it's necessary to point out that no one has ever been able to make Darwin's argument make sense either. Not in the field and not in actual observation. If change has one mechanism, it's got more going for it than dumb luck.

And for all the reasons listed above, Darwinism was nearly dead by the early 20th Century. It's not a science, it's an anti-religion. You can't “do science” with it. But the discovery of DNA blew some life into the golem and neo-Darwinism was born. Now the “slight, successive and accidental” changes would be conferred onto the genome. That is, “random mutations” of DNA would be blamed for, or credited with, turning that bear into a whale.

And none of it has worked out. The genome does not behave as the arrogant young men (James Watson and Francis Crick - see Chapter 6 on HIV) thought it should. DNA doesn't change “slightly” or “randomly.” The small changes, the accidental errors in copying, are sorted out by the micro-machines inside the cell. If they aren't, the cell is diseased and either becomes part of a disease mass, or is cleaned out by the body.

DNA works in leaps and bounds and full-scale shuffling of sectors. These are not accidental. They are actively programmed and completed by the micro-machines inside the cell. Darwinism has died twice. Neo-Darwinism is dead as a research method because change inside the genome is not “slight, successive and accidental.” And changes in the genome do not necessarily bring changes to the exterior of the whole creature. And the genome is, in fact, influenced by the environment (more on that in a moment).

Beneath the Surface

Charles Darwin had no concept of DNA, or the interior of cells. He looked at organisms as nearly indivisible objects. From the outside, a possum looks like a rat and so is a kind of a rat, a little slower and larger, with poorer vision. But biologists, taking these animals apart, found that they give birth through a very different mechanism. One is a marsupial and the other has an internal womb. But that’s not all.

Biologists taking the variety of lifeforms apart to examine them, structurally, mechanically and chemically, are struck dumb by the internal differences and complexities of even the tiniest organs in our bodies. Each of our organs and body parts - eyes, ears, nose, mouth, lips, tongue, swallowing mechanisms, digestive fluids, excretory paths and methods of reproduction - are layered worlds of inter-locking, hierarchical complexity, that cannot be seen or appreciated by examining only shape and size, or habitat, as Darwin did.

We are made of cells that are symbiotically inter-developed and woven together from what look like different species of microscopic organisms, as though nature, or the mind of the universe, likes to mix, match and combine already existing forms.

We have a liver that is a planet of activity, performing 500 separate metabolic functions. Above the purely biological, we, the creatures of the planet, manifest a panoply of social habits, widely diverse methods of communication, strong inter-dependence and symbiotic inter-development at every level, from the micro to the macroscopic.

How does an interlocking system of skyrocketing complexity develop by accident? How does it change its symphonic orchestration to an entirely new tune by “random chance?”

Answer: it doesn't. The intelligence of the universe is reflected inside and outside. The macroscopic mirrors the microscopic. The small recapitulates the large and vice-versa. The cells in our bodies look like the cellular structures of plasma in space (see Chapter 9). Our veins look like tree roots and branches, which look like the paths of rivers on the ground and electricity in the sky. These are the ever-present guiding pathways of the essentially creative universe.

Darwin had no concept of the microscopic world. If he had, he might have been more humble. If a plant cell looked like a bit of clear jelly to his eyes, under a powerful microscope it looks like a three-dimensional, zero-gravity, jet-fighter factory floor. Self-propelling micro-machines walking, motoring, floating and flying through liquid, in an insanely clever, awe-inspiring intergalactic star-cruiser, working at speeds which we can not propel ourselves even by sheer determination. Multi-tasking in ways that the most powerful computers can not do.

And we're supposed to believe that this is all a big, dumb accident? It's a genius machine of such magnitude that if we saw such a thing on the surface of another planet or moon, we would know that we were witnessing a civilization so in advance of us, that we ought to surrender and beg for a thousand years of slavery, just to learn their God-like technology.

And this is what is inside of us, in every living cell.

This is now known to genetic researchers, like James Shapiro (author of “Mobile DNA and Evolution in the 21st Century”), who have made it clear that Darwinism is, indeed, quite and entirely dead. He calls what goes on in our cells “natural genetic engineering.” The little micro-robots that are us, re-configure our genetic material and cellular environments infinitely better and faster than our top geneticists can do on their best day with the most advanced equipment. Which means that something in us is smarter than we are.

While our heads are locked in philosophical arguments with the 16th Century, our bodies are the most complex symphony of every kind of music operating in three-dimensional space, in every part of our body. In our micro-machining cells, we are, to quote those who've been arguing against Darwinism for some time, irreducibly complex.

We're formed of a trillion trillion micro-machines, hooked in, stacked up, piled into nested hierarchies, performing acts of death-defying anti-gravity, in each and every one of the cells in our eyes, noses, big toes and bottoms. So, sit on that for a moment.

And the brave and brazen in the research set are finally understanding it. No, it's not “random chance” that brings change. It's - ready? Our environment.

Take that, Charles. (You should have stuck with Antoine.)

Foxy

A few decades ago, a group of wild foxes in Russia were caught, caged and then picked to breed. The foxes which were selected to breed were chosen for one quality - their lack of fear of humans. While the majority of wild foxes recoiled or attacked, hissed and bit at a human hand coming to touch or pet them, some responded little, or not at all.

These calmer foxes were allowed to mate and the calmer of their offspring and so on for multiple generations. They were not socialized or trained by people, they were only bred for one response. Within three generations, the foxes were markedly tamer. Within eight generations something insanely wonderful happened. They liked people.

No, they loved people. Needed to be around people. Formed relationships with people. They yipped and barked and played games and licked and nuzzled and followed people around. And they exhibited this behavior from infancy. Which foxes do not do.

But it was not just social and behavioral change. Within a few generations, their physical appearances also altered significantly. Their ears flopped, their tails curled, their limbs were a little shorter and they were mottled, black and white, not just dark grey. Unlike every fox they'd descended from.

One quality was “intelligently” selected for and a tidal wave of visible, mental and social qualities changed, radically. Slight, successive and random? Not in real life.

When Darwinians talk about “change over time,” they don't mean change within a few generations, or even a hundred. They mean over hundreds of thousands of years. They're asking you to believe in what you can never see. That's the official defense of Darwinian evolution: you can't see it, you just have to imagine it. And you certainly can’t experiment with it.

But you can experiment with rapid change, both physical and behavioral, brought on by selective breeding for only one characteristic. Which would indicate that Darwinism is, indeed, dead. And good riddance, really.

This study of real and rapid change is the new science. Do you know what it is called? Neo-Lamarckism. Oh, the irony. He was wrong until he was right. As for the mechanisms of change, the “epi-geneticists” (for “above or outside of genetics”) like to look at things like retroviruses. You remember retroviruses. They don't kill T-cells, but they may be engineers of a variety of changes in the body, relaying information from the outside, to the inside. It's a two-way street.

And it's not just the wild foxes. Agouti lab mice whose parents have nutrients withheld come out yellow-haired and grow fat and sick. Mice of the same species whose parents are fed a nutritious diet come out sleek and grey and are resistant to disease. In more detail, if they are given foods which provide methyl groups to DNA (like onions, garlic and beets), they express a wildly different physiology than if they are starved for the nutrients. These cousins look like different species and it all happened through diet. The lesson is, DNA expresses differently when fed essential nutrients.

Likewise, fly eggs exposed to chemicals give rise to flies with too many or too few wings, eyes or legs. The changes are vast and fast. The environment profoundly influences the organism.

It's become so clear that the genome is affected directly by chemical, stress, nutritional and environmental factors, that Watson and Crick's “Central Dogma” has given way to the more accurate description of a “fluid genome.” And there are Antoine's “humors,” coursing through the body.

Poor Antoine de Lamarck. Like Antoine Béchamp (Chapter 5), he must be watching from the other plane, saying, “Well, better late than never, you morons.”

No One Is To Blame

Most of what we call laboratory science today has its roots in a rejection of a particular kind of religion; a religion of opposition. But the single-pointed inversion of an untruth is not truth. The reaction of a bad idea is not a good idea, it's just another idea. A rejection of Christianity is not science, it is anti-Christianity.

And that's all Darwinism ever was. There is no science to it. There is no algebra that can be done with fitness, randomness and chance, that will turn a worm into a lizard, or a bear into a whale, when all that are allowed to be factored in are “accident” and “time.”

It is the environment that motivates a responsive, active change in the organism, which most clearly effects it in its “plastic state,” as it's developing. Understanding how life likes to alter would be a good thing to do, if we wanted mothers to give birth to healthy babies. Because we'd have to pay close attention to what chemicals we were dumping into our living environments, our seas, lakes and fields.

Of course, that is what “Darwinism” has over neo-Lamarckism. If life is an accident, then factories can pollute and damage our entire planetary living space, because all the sickness that we experience as a result, that is manifested so strongly in children, can be blamed on something other than the companies which are directly responsible.

Just as modern medicine blames “viruses” for toxicological and chemical poisonings caused by industry (see Chapter 5), Darwinism, the “accidental and blind” theory of life, lets us off the hook for the damage we do to ourselves and our fellow travelers on the planet. Their argument, that change is “accidental” and the environment plays no role in determining our fate, has convinced us that we can do anything we want to our surroundings without affecting our insides.

But if just the opposite is true, then every bit of poison we throw into the land and water is flowing into our gene pool. Which is a hell of a thought, if you look at what factories belch into our rivers, lakes and oceans and pour on our farmland and fields.

If there is one lesson to be learned from the “Century of Darwin,” I would offer this: we are inextricably woven into an immensely intelligent and creative universe. Just watch a David Attenborough series if you don't think that there is an incredibly brilliant mind, not at work, but at play, present in all of us. We're foolish to try to define the mind that spins it all. We're foolish to believe that our literal-minded myths are enough to encapsulate it. We should take more pleasure in describing each unfolding mystery and less in trying to fit it into a predetermined box. And if we want to be healthy, as a species, we'd better stop poisoning ourselves from the outside in.

Or, that's my Amen.

Darwin’s idea that life wanders from one variation to the next, never committing, always yielding to the blind force of natural selection, is plainly incompatible with the idea that the physical forms of life are expressions of something deeper, something immovable, something perfect.

Undeniable – Douglas Axe

Stephen Meyer

Darwin’s Doubt: Prologue

When people today hear the term “information revolution,” they typically think of silicon chips and software code, cellular phones and supercomputers. They rarely think of tiny one-celled organisms or the rise of animal life. But, while writing these words in the summer of 2012, I am sitting at the end of a narrow medieval street in Cambridge, England, where more than half a century ago a far-reaching information revolution began in biology. This revolution was launched by an unlikely but now immortalized pair of scientists, Francis Crick and James Watson. Since my time as a Ph.D. student at Cambridge during the late 1980s, I have been fascinated by the way their discovery transformed our understanding of the nature of life. Indeed, since the 1950s, when Watson and Crick first illuminated the chemical structure and information-bearing properties of DNA, biologists have come to understand that living things, as much as high-tech devices, depend upon digital information—information that, in the case of life, is stored in a four-character chemical code embedded within the twisting figure of a double helix.

Because of the importance of information to living things, it has now become apparent that many distinct “information revolutions” have occurred in the history of life—not revolutions of human discovery or invention, but revolutions involving dramatic increases in the information present within the living world itself. Scientists now know that building a living organism requires information, and building a fundamentally new form of life from a simpler form of life requires an immense amount of new information. Thus, wherever the fossil record testifies to the origin of a completely new form of animal life—a pulse of biological innovation—it also testifies to a significant increase in the information content of the biosphere.

In 2009, I wrote a book called Signature in the Cell about the first “information revolution” in the history of life—the one that occurred with the origin of the first life on earth. My book described how discoveries in molecular biology during the 1950s and 1960s established that DNA contains information in digital form, with its four chemical subunits (called nucleotide bases) functioning like letters in a written language or symbols in a computer code. And molecular biology also revealed that cells employ a complex information-processing system to access and express the information stored in DNA as they use that information to build the proteins and protein machines that they need to stay alive. Scientists attempting to explain the origin of life must explain how both information-rich molecules and the cell’s information-processing system arose.

The type of information present in living cells—that is, “specified” information in which the sequence of characters matters to the function of the sequence as a whole—has generated an acute mystery. No undirected physical or chemical process has demonstrated the capacity to produce specified information starting “from purely physical or chemical” precursors. For this reason, chemical evolutionary theories have failed to solve the mystery of the origin of first life—a claim that few mainstream evolutionary theorists now dispute.

In Signature in the Cell, I not only reported the well-known impasse in origin-of-life studies; I also made an affirmative case for the theory of intelligent design. Although we don’t know of a material cause that generates functioning digital code from physical or chemical precursors, we do know—based upon our uniform and repeated experience—of one type of cause that has demonstrated the power to produce this type of information. That cause is intelligence or mind. As information theorist Henry Quastler observed, “The creation of information is habitually associated with conscious activity.”1 Whenever we find functional information—whether embedded in a radio signal, carved in a stone monument, etched on a magnetic disc, or produced by an origin-of-life scientist attempting to engineer a self-replicating molecule—and we trace that information back to its ultimate source, invariably we come to a mind, not merely a material process. For this reason, the discovery of digital information in even the simplest living cells indicates the prior activity of a designing intelligence at work in the origin of the first life.

Eliminating chance is closely connected with design and intelligent agency. To eliminate chance because a sufficiently improbable event conforms to the right sort of pattern is frequently the first step in identifying an intelligent agent. It makes sense, therefore, to define design as "patterned improbability," and the design inference as the logic by which "patterned improbability" is detected and demonstrated.

So defined, the design inference stops short of delivering a causal story for how an intelligent agent acted. But by precluding chance and implicating intelligent agency, the design inference does the next best thing.

The Design Inference – William Dembski

My book proved controversial, but in an unexpected way. Though I clearly stated that I was writing about the origin of the first life and about theories of chemical evolution that attempt to explain it from simpler preexisting chemicals, many critics responded as if I had written another book altogether. Indeed, few attempted to refute my book’s actual thesis that intelligent design provides the best explanation for the origin of the information necessary to produce the first life. Instead, most criticized the book as if it had presented a critique of the standard neo-Darwinian theories of biological evolution—theories that attempt to account for the origin of new forms of life from simpler preexisting forms of life. Thus, to refute my claim that no chemical evolutionary processes had demonstrated the power to explain the ultimate origin of information in the DNA (or RNA) necessary to produce life from simpler preexisting chemicals in the first place, many critics cited processes at work in already living organisms—in particular, the process of natural selection acting on random mutations in already existing sections of information-rich DNA. In other words, these critics cited an undirected process that acts on preexistent information-rich DNA to refute my argument about the failure of undirected material processes to produce information in DNA in the first place.

For example, the eminent evolutionary biologist Francisco Ayala attempted to refute Signature by arguing that evidence from the DNA of humans and lower primates showed that the genomes of these organisms had arisen as the result of an unguided, rather than intelligently designed, process—even though my book did not address the question of human evolution or attempt to explain the origin of the human genome, and even though the process to which Ayala alluded clearly presupposed the existence of another information-rich genome in some hypothetical lower primate.

Other discussions of the book cited the mammalian immune system as an example of the power of natural selection and mutation to generate new biological information, even though the mammalian immune system can only perform the marvels it does because its mammalian hosts are already alive, and even though the mammalian immune system depends upon an elaborately preprogrammed form of adaptive capacity rich in genetic information—one that arose long after the origin of the first life. Another critic steadfastly maintained that “Meyer’s main argument” concerns “the inability of random mutation and selection to add information to [preexisting] DNA” and attempted to refute the book’s presumed critique of the neo-Darwinian mechanism of biological evolution accordingly.

I found this all a bit surreal, as if I had wandered into a lost chapter from a Kafka novel. Signature in the Cell simply did not critique the theory of biological evolution, nor did it ask whether mutation and selection can add new information to preexisting information-rich DNA. To imply otherwise, as many of my critics did, was simply to erect a straw man.

To those unfamiliar with the particular problems faced by scientists trying to explain the origin of life, it might not seem obvious why invoking natural selection does not help to explain the origin of the first life. After all, if natural selection and random mutations can generate new information in living organisms, why can it also not do so in a prebiotic environment? But the distinction between a biological and prebiotic context was crucially important to my argument. Natural selection assumes the existence of living organisms with a capacity to reproduce. Yet self-replication in all extant cells depends upon information-rich proteins and nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), and the origin of such information-rich molecules is precisely what origin-of-life research needs to explain. That’s why Theodosius Dobzhansky, one of the founders of the modern neo-Darwinian synthesis, can state flatly, “Pre-biological natural selection is a contradiction in terms.” Or, as Nobel Prize–winning molecular biologist and origin-of-life researcher Christian de Duve explains, theories of prebiotic natural selection fail because they “need information which implies they have to presuppose what is to be explained in the first place.” Clearly, it is not sufficient to invoke a process that commences only once life has begun, or once biological information has arisen, to explain the origin of life or the origin of the information necessary to produce it.

All this notwithstanding, I have long been aware of strong reasons for doubting that mutation and selection can add enough new information of the right kind to account for large-scale, or “macroevolutionary,” innovations—the various information revolutions that have occurred after the origin of life. For this reason, I have found it increasingly tedious to have to concede, if only for the sake of argument, the substance of claims I think likely to be false.

And so the repeated prodding of my critics has paid off. Even though I did not write the book or make the argument that many of my critics critiqued in responding to Signature in the Cell, I have decided to write that book. And this is that book.

Of course, it might have seemed a safer course to leave well enough alone. Many evolutionary biologists now grudgingly acknowledge that no chemical evolutionary theory has offered an adequate explanation of the origin of life or the ultimate origin of the information necessary to produce it. Why press a point you never made in the first place?

Because despite the widespread impression to the contrary—conveyed by textbooks, the popular media, and spokespersons for official science—the orthodox neo-Darwinian theory of biological evolution has reached an impasse nearly as acute as the one faced by chemical evolutionary theory. Leading figures in several subdisciplines of biology—cell biology, developmental biology, molecular biology, paleontology, and even evolutionary biology—now openly criticize key tenets of the modern version of Darwinian theory in the peer-reviewed technical literature. Since 1980, when Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould declared that neo-Darwinism “is effectively dead, despite its persistence as textbook orthodoxy,” the weight of critical opinion in biology has grown steadily with each passing year.

A steady stream of technical articles and books have cast new doubt on the creative power of the mutation and selection mechanism. So well established are these doubts that prominent evolutionary theorists must now periodically assure the public, as biologist Douglas Futuyma has done, that “just because we don’t know how evolution occurred, does not justify doubt about whether it occurred.” Some leading evolutionary biologists, particularly those associated with a group of scientists known as the “Altenberg 16,” are openly calling for a new theory of evolution because they doubt the creative power of the mutation and natural selection mechanism.

The fundamental problem confronting neo-Darwinism, as with chemical evolutionary theory, is the problem of the origin of new biological information. Though neo-Darwinists often dismiss the problem of the origin of life as an isolated anomaly, leading theoreticians acknowledge that neo-Darwinism has also failed to explain the source of novel variation without which natural selection can do nothing—a problem equivalent to the problem of the origin of biological information. Indeed, the problem of the origin of information lies at the root of a host of other acknowledged problems in contemporary Darwinian theory—from the origin of new body plans to the origin of complex structures and systems such as wings, feathers, eyes, echolocation, blood clotting, molecular machines, the amniotic egg, skin, nervous systems, and multicellularity, to name just a few.

At the same time, classical examples illustrating the prowess of natural selection and random mutations do not involve the creation of novel genetic information. Many biology texts tell, for example, about the famous finches in the Galápagos Islands, whose beaks have varied in shape and length over time. They also recall how moth populations in England darkened and then lightened in response to varying levels of industrial pollution. Such episodes are often presented as conclusive evidence for the power of evolution. And indeed they are, depending on how one defines “evolution.” That term has many meanings, and few biology textbooks distinguish between them. “Evolution” can refer to anything from trivial cyclical change within the limits of a preexisting gene pool to the creation of entirely novel genetic information and structure as the result of natural selection acting on random mutations. As a host of distinguished biologists have explained in recent technical papers, small-scale, or “microevolutionary,” change cannot be extrapolated to explain large-scale, or “macroevolutionary,” innovation. For the most part, microevolutionary changes (such as variation in color or shape) merely utilize or express existing genetic information, while the macroevolutionary change necessary to assemble new organs or whole body plans requires the creation of entirely new information. As an increasing number of evolutionary biologists have noted, natural selection explains “only the survival of the fittest, not the arrival of the fittest.” The technical literature in biology is now replete with world-class biologists routinely expressing doubts about various aspects of neo-Darwinian theory, and especially about its central tenet, namely, the alleged creative power of the natural selection and mutation mechanism.

Nevertheless, popular defenses of the theory continue apace, rarely if ever acknowledging the growing body of critical scientific opinion about the standing of the theory. Rarely has there been such a great disparity between the popular perception of a theory and its actual standing in the relevant peer-reviewed scientific literature. Today modern neo-Darwinism seems to enjoy almost universal acclaim among science journalists and bloggers, biology textbook writers, and other popular spokespersons for science as the great unifying theory of all biology. High-school and college textbooks present its tenets without qualification and do not acknowledge the existence of any significant scientific criticism of it. At the same time, official scientific organizations—such as the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS), and the National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT)—routinely assure the public that the contemporary version of Darwinian theory enjoys unequivocal support among qualified scientists and that the evidence of biology overwhelmingly supports the theory. For example, in 2006 the AAAS declared, “There is no significant controversy within the scientific community about the validity of the theory of evolution.” The media dutifully echo these pronouncements. As New York Times science writer Cornelia Dean asserted in 2007, “There is no credible scientific challenge to the theory of evolution as an explanation for the complexity and diversity of life on earth.”

The extent of the disparity between popular representations of the status of the theory and its actual status, as indicated in the peer-reviewed technical journals, came home to me with particular poignancy as I was preparing to testify before the Texas State Board of Education in 2009. At the time the board was considering the adoption of a provision in its science education standards that would encourage teachers to inform students of both the strengths and weaknesses of scientific theories. This provision had become a political hot potato after several groups asserted that “teaching strengths and weaknesses” were code words for biblical creationism or for removing the teaching of the theory of evolution from the curriculum. Nevertheless, after defenders of the provision insisted that it neither sanctioned teaching creationism nor censored evolutionary theory, opponents of the provision shifted their ground. They attacked the provision by insisting that there was no need to consider weaknesses in modern evolutionary theory because, as Eugenie Scott, spokeswoman for the National Center for Science Education, insisted in The Dallas Morning News, “There are no weaknesses in the theory of evolution.”

At the same time, I was preparing a binder of one hundred peer-reviewed scientific articles in which biologists described significant problems with the theory—a binder later presented to the board during my testimony. So I knew—unequivocally—that Dr. Scott was misrepresenting the status of scientific opinion about the theory in the relevant scientific literature. I also knew that her attempts to prevent students from hearing about significant problems with evolutionary theory would have likely made Charles Darwin himself uncomfortable. In On the Origin of Species, Darwin openly acknowledged important weaknesses in his theory and professed his own doubts about key aspects of it. Yet today’s public defenders of a Darwin-only science curriculum apparently do not want these, or any other scientific doubts about contemporary Darwinian theory, reported to students.

This book addresses Darwin’s most significant doubt and what has become of it. It examines an event during a remote period of geological history in which numerous animal forms appear to have arisen suddenly and without evolutionary precursors in the fossil record, a mysterious event commonly referred to as the “Cambrian explosion.” As he acknowledged in the Origin, Darwin viewed this event as a troubling anomaly—one that he hoped future fossil discoveries would eventually eliminate.

The book is divided into three main parts. Part One, “The Mystery of the Missing Fossils,” describes the problem that first generated Darwin’s doubt—the missing ancestors of the Cambrian animals in the earlier Precambrian fossil record—and then tells the story of the successive, but unsuccessful, attempts that biologists and paleontologists have made to resolve that mystery.

Part Two, “How to Build an Animal,” explains why the discovery of the importance of information to living systems has made the mystery of the Cambrian explosion more acute. Biologists now know that the Cambrian explosion not only represents an explosion of new animal form and structure but also an explosion of information—that it was, indeed, one of the most significant “information revolutions” in the history of life. Part Two examines the problem of explaining how the unguided mechanism of natural selection and random mutations could have produced the biological information necessary to build the Cambrian animal forms. This group of chapters explains why so many leading biologists now doubt the creative power of the neo-Darwinian mechanism and it presents four rigorous critiques of the mechanism based on recent biological research.

Part Three, “After Darwin, What?” evaluates more current evolutionary theories to see if any of them explain the origin of form and information more satisfactorily than standard neo-Darwinism does. Part Three also presents and assesses the theory of intelligent design as a possible solution to the Cambrian mystery. A concluding chapter discusses the implications of the debate about design in biology for the larger philosophical questions that animate human existence. As the story of the book unfolds, it will become apparent that a seemingly isolated anomaly that Darwin acknowledged almost in passing has grown to become illustrative of a fundamental problem for all of evolutionary biology: the problem of the origin of biological form and information.

To see where that problem came from and why it has generated a crisis in evolutionary biology, we need to begin at the beginning: with Darwin’s own doubt, with the fossil evidence that elicited it, and with a clash between a pair of celebrated Victorian naturalists—the famed Harvard paleontologist Louis Agassiz and Charles Darwin himself.

Michael Behe

Darwin’s Black Box (excerpts)

For more than a century most scientists have thought that virtually all of life, or at least all of its most interesting features, resulted from natural selection working on random variation. Darwin's idea has been used to explain finch beaks and horse hoofs, moth coloration and insect slaves, and the distribution of life around the globe and through the ages. The theory has even been stretched by some scientists to interpret human behavior: why desperate people commit suicide, why teenagers have babies out of wedlock, why some groups do better on intelligence tests than other groups, and why religious missionaries forgo marriage and children. There is nothing—no organ or idea, no sense or thought—that has not been the subject of evolutionary rumination.

Almost a century and a half after Darwin proposed his theory, evolutionary biology has had much success in accounting for patterns of life we see around us. To many, its triumph seems complete. But the real work of life does not happen at the level of the whole animal or organ; the most important parts of living things are too small to be seen. Life is lived in the details, and it is molecules that handle life's details. Darwin's idea might explain horse hoofs, but can it explain life's foundation?

Shortly after 1950 science advanced to the point where it could determine the shapes and properties of a few of the molecules that make up living organisms. Slowly, painstakingly, the structures of more and more biological molecules were elucidated, and the way they work inferred from countless experiments. The cumulative results show with piercing clarity that life is based on machines—machines made of molecules! Molecular machines haul cargo from one place in the cell to another along «highways» made of other molecules, while still others act as cables, ropes, and pulleys to hold the cell in shape. Machines turn cellular switches on and off, sometimes killing the cell or causing it to grow. Solar-powered machines capture the energy of photons and store it in chemicals. Electrical machines

allow current to flow through nerves. Manufacturing machines build other molecular machines, as well as themselves. Cells swim using machines, copy themselves with machinery, ingest food with machinery. In short, highly sophisticated molecular machines control every cellular process. Thus the details of life are finely calibrated, and the machinery of life enormously complex.

--

The key to persuading people was the portrayal of the cells as «simple.» One of the chief advocates of the theory of spontaneous generation during the middle of the nineteenth century was Ernst Haeckel, a great admirer of Darwin and an eager popularizer of Darwin's theory. From the limited view of cells that microscopes provided, Haeckel believed that a cell was a «simple little lump of albuminous combination of carbon,» not much different from a piece of microscopic Jell-O. So it seemed to Haeckel that such simple life, with no internal organs, could be produced easily from inanimate material. Now, of course, we know better.

Here is a simple analogy: Darwin is to our understanding of the origin of vision as Haeckel is to our understanding of the origin of life. In both cases brilliant nineteenth-century scientists tried to explain Lilliputian biology that was hidden from them, and both did so by assuming that the inside of the black box must be simple. Time has proven them wrong.

--

Now that the black box of vision has been opened, it is no longer enough for an evolutionary explanation of that power to consider only the anatomical structures of whole eyes, as Darwin did in the nineteenth century (and as popularizers of evolution continue to do today). Each of the anatomical steps and structures that Darwin thought were so simple actually involves staggeringly complicated biochemical processes that cannot be papered over with rhetoric. Darwin's metaphorical hops from butte to butte are now revealed in many cases to be huge leaps between carefully tailored machines—distances that would require a helicopter to cross in one trip.

--

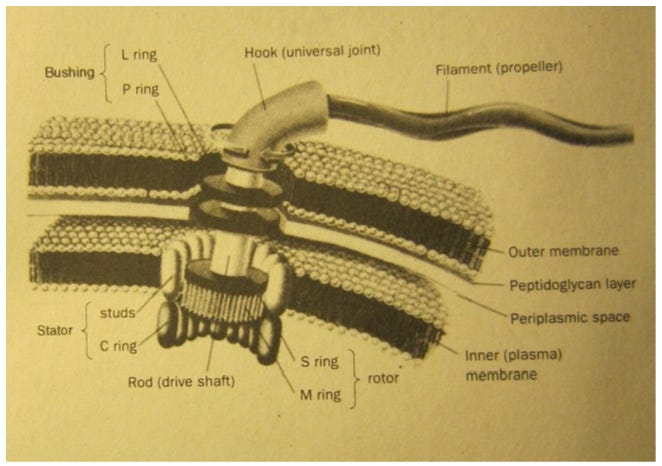

The bacterial flagellum uses a paddling mechanism. Therefore it must meet the same requirements as other such swimming systems. Because the bacterial flagellum is necessarily composed of at least three parts—a paddle, a rotor, and a motor—it is irreducibly complex. Gradual evolution of the flagellum, like the cilium, therefore faces mammoth hurdles.

The general professional literature on the bacterial flagellum is about as rich as the literature on the cilium, with thousands of papers published on the subject over the years. That isn't surprising; the flagellum is a fascinating biophysical system, and flagellated bacteria are medically important. Yet here again, the evolutionary literature is totally missing. Even though we are told that all biology must be seen through the lens of evolution, no scientist has ever published a model to account for the gradual evolution of this extraordinary molecular machine.

"As the century and with it the millennium come to an end, questions long buried have disinterred themselves and come clattering back to intellectual life, dragging their winding sheets behind them. Just what, for example, is the origin of biological complexity and how is it to be explained? We have no more idea today than Darwin did in 1859, which is to say no idea whatsoever.

David Berlinski, Author of The Tour of the Calculus

Thank you for reading and hopefully sharing this Substack.

Please consider a small paid subscription (donation). The money goes to a good cause.

I am always looking for good, personal GMC, covid and childhood vaccination stories. Please email me.

In the comments, please let me know what’s on your mind.

You can write to me privately: unbekoming@outlook.com

If you are Covid vaccine injured, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment

If you want to understand and “see” what baseline human health looks like, watch this 21 minutes.

Here are three eBooks I have produced so far:

FREE eBook: A letter to my two adult kids - Vaccines and the free spike protein

Darwin’s evolutionary tree of life, as depicted by the nineteenth-century German evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel.