One makes a mandorla every time one says something that is true.

I first read Owning Your Own Shadow in the late 90s. I got what I was able to get out of it at the time. For, the teacher arrives when the student is ready.

I’ve read it a few times since and get something new and different out of it each time.

I wrote this to a young friend once introducing him to the mandorla…

The attached is one of my favourite books that I have picked up and read multiple times over the years, each time I learn several new things. It was where I discovered the Mandorla (the Almond between the two circles). I would recommend anyone to read and reread because what you will understand will differ at 20 vs 30 vs 40 etc. But if nothing else the third and last chapter talks about The Mandorla. For me personally I have found it to be the most important idea I have ever come across, and, for me, an invisible guiding compass in all things (if I cannot find it, that’s on me…but it’s always there).

…we caught up recently and this time he was the one reminding me of the mandorla.

If you get something out of it, I encourage you to buy short Johnson’s book. It’s worth getting to know his work. He brought Jung to a wider audience, and Peterson is doing that again now in his own way. There’s something about Jung that is bottomless and there to be mined for a lifetime.

This is a slight change in subject matter for this Substack, but I think in the context of the psychological damage they have inflicted on us over the last three years, and especially on the young, I think it’s time to start writing about tools and perspectives, that I feel I have something to say about, that can help with rebalancing and recovery. I know that I have quite a few young people reading my stuff, and this is mainly aimed at them, although clearly this is relevant for all ages.

Alot of things have been shoved into our shadows during the GMC, and we are going to need to better our understanding of our shadows and also get better at integrating them back into the whole. If you are new to the shadow, it will make a bit more sense at the end of this stack, or ideally read the whole of Johnson’s short book, and definitely watch the Academy of Ideas videos.

Without further ado, here is The Mandorla (Chapter 3 of a very short book). I hope you find it as interesting and useful as I have.

With thanks and appreciation to Robert Johnson.

The Mandorla

Thank God, there is a concept to rescue us from the usual impasse. Happily, we have it in our own Christian culture and do not have to go to exotic places for a solution.

This is the mandorla, an idea from medieval Christianity that is all but unknown today. You will find it in any book on medieval theology but one rarely finds it talked about at present. It is far too valuable a concept to have lost.

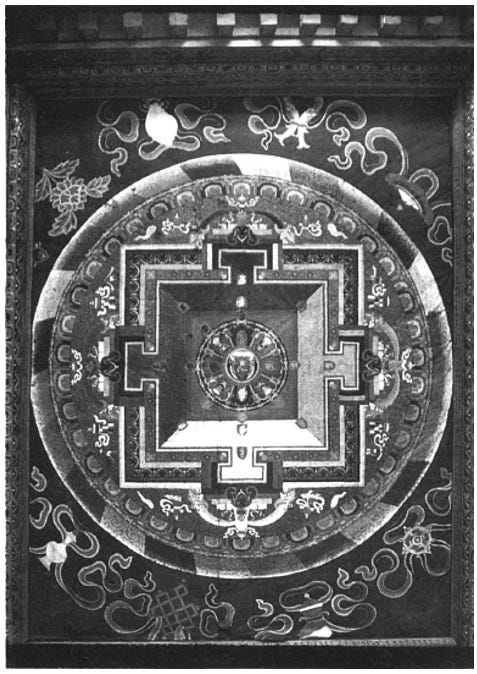

Everyone knows what a mandala is, even though mandala is a Sanskrit term borrowed from India and Tibet. A mandala is a holy circle or bounded place that is a representation of wholeness. We often find this image in the Tibetan tanka, a picture, generally of the Buddha with his many attributes, that hangs on the wall of a prayer room or temple as a reminder of the wholeness of life. Mandalas are devices that remind us of our unity with God and with all living things. In Tibet a teacher often draws a mandala for his student and leaves him to meditate on this symbol for many years before he gives the next step of instruction. The mandala is also found in the rose window in Gothic architecture, and it appears frequently as a healing symbol in Christian art. Mandalas turn up in dreams when the personality is especially fragmented and the dreamer needs this calming symbol. During a particularly taxing time in his life, Dr. Jung drew a mandala every morning to keep his sense of balance and proportion.

The mandorla also has a healing effect, but its form is somewhat different. A mandorla is that almond-shaped segment that is made when two circles partly overlap. It is not by chance that mandorla is also the Italian word for almond. This symbol signifies nothing less than the overlap of the opposites that we have been investigating. Generally, the mandorla is described as the overlap of heaven and earth. There is not one of us who is not torn by the competing demands of heaven and earth; the mandorla instructs us how to engage in reconciliation. Christ and the Virgin are often portrayed within the framework of the mandorla. This reminds us that we partake of the nature of both heaven and earth. Christianity makes a wonderful affirmation of the feminine element of life by giving it a place in the mandorla, and the Virgin sits in majesty in the mandorla as often as Christ. The finest examples of the mandorla appear in the west portals of many of the great cathedrals in Europe, with Christ or the Virgin framed this way.

The Healing Nature of the Mandorla

The mandorla is so important for our torn world that we will explore it in detail. We have been talking about pairs of opposites in our examination of the shadow. It has been the nature of our cultural life to set a good possibility against a bad one and banish the bad one so thoroughly that we lose track of its existence. These banished elements make up our shadow, but they will not stay in exile forever, and about midlife they come back like Old Testament scapegoats returning from the desert.

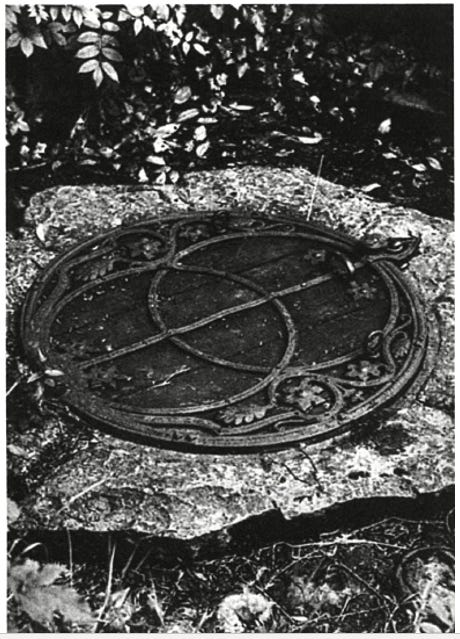

Mandorla. The Chalice Well, Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Courtesy of Thames & Hudson. Photograph by Reece Winstone.

Mandala. Bhutan wall painting. Photograph by Tom Braise.

What can one do when the banished elements demand a day of reckoning? Then it is time for an understanding of the mandorla.

The mandorla has a wonderfully healing and encouraging function. When one is tired or discouraged or so battered by life that one can no longer live in the tension of the opposites, the mandorla shows what one may do. When the most herculean efforts and the finest discipline no longer keep the painful contradictions of life at bay, we are all in need of the mandorla. It helps us transfer from a cultural life to a religious life. (Fortunately, this does not end our cultural life, for by now it is well enough established to survive on its own.)

The mandorla begins the healing of the split. The overlap generally is very tiny at first, only a sliver of a new moon; but it is a beginning. As time passes, the greater the overlap, the greater and more complete is the healing. The mandorla binds together that which was torn apart and made unwhole—unholy. It is the most profound religious experience we can have in life.

Language as Mandorla

All language is a mandorla; a well-structured sentence is of this nature. That is probably why we like to talk so much; good talk restores unity to a fragmented world. A badly formed sentence with poor grammatical structure offends us—probably because it overlaps elements poorly and fails in its unifying task.

Our principal verb to be is the great unifier. A sentence with the verb to be is a statement of identity and heals the split between two elements. This is honored by observing the subjective form for the predicate of the verb to be. We say, “I am he.” not “I am him.” I and he are the same, a statement of the mystical union of diversity.

All sentences make identity even apart from the verb to be, though it may be less obvious. Every verb makes holy ground. “I will go home” or “I will play music now” imply a special identity to “I” and “home” or “I” and “music.” To make any well formed sentence is to make unity out of duality. This is immensely healing and restorative. We are all poets and healers when we use language correctly. One makes a mandorla every time one says something that is true.

A sentence is something like a mathematical equation with the verb representing the equal sign. A correct sentence says that the subject equals the object and annuls the quarrel between the two. The split inherent in duality is healed.

Languages rich in verbs are more powerful than those relying mostly on nouns. Chinese and Hebrew are the former. Human speech is more effective if it relies mainly on verbs. If you build mainly on nouns it will be weak; if you rely on adjectives and adverbs you have lost your way. The verb is holy ground, the place of the mandorla. One can examine the great speeches of Shakespeare to find the nobility and the healing power of strong verbs.

A friend sent me a tape recorder long before they were in common use. Instructions were noted: “Plug this in, press button A, listen to the tape on the machine. Then turn the tape over, press button B, and make a tape in reply.” For a minute or two when I began my taped response, I was awkward; I couldn’t think of anything to say. Yet when the tape ran out an hour later I was angry, for I had not nearly exhausted all I wanted to express. Thus began a tape correspondence that was extremely valuable to me. When I was distressed, I would make a tape and find that I had often talked my way through a dilemma. I did what Freud called “the talking cure,” for language, properly used, is a highly curative agency. My friend lives far away and we meet infrequently. At one rare meeting my friend said, “Robert, why is it that you are so much more intelligent on tape than in conversation? Don’t answer; I know. On the tape I don’t interrupt!” Talking to him by tape had engaged my feeling function and given me the freedom to process my own thoughts. You can give another person a precious gift if you will allow him to talk without contaminating his speech with your own material. Given the right container, we can make mandorlas of speech and cure many things. We become poets in our own right in the proper circumstances.

It is a miracle to listen to someone (even oneself) say, “Perhaps this, perhaps that, maybe, it follows that, I wonder if”—all like a dog chasing its tail. But gradually, the two disparate circles begin to overlap and the mandorla grows. This is healing. This is ligature, the essence of religious experience.

All good stories are mandorlas. They speak of this and that and gradually, through the miracle of story, demonstrate that the opposites overlap and are finally the same. We like to think that a story is based on the triumph of good over evil; but the deeper truth is that good and evil are superseded and the two become one. Since our capacity for synthesis is limited, many stories can only hint at this unity. But any unity, even a hint, is healing.

Do you remember the story of Moses and the burning bush? There are many bushes and much burning; but in this story the bush and the burning overlap; the bush is not consumed and we know that two orders of reality have been superimposed. In a moment we find that God is near—the result of the overlap.

Whenever you have a clash of opposites in your being and neither will give way to the other (the bush will not be consumed and the fire will not stop), you can be certain that God is present. We dislike this experience intensely and avoid it at any cost; but if we can endure it, the conflict-without-resolution is a direct experience of God.

A mandorla is a prototype of conflict resolution. It is the art of healing, if you will. Shakespeare wrote of his art:

The poet’s eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.*

Here Shakespeare is reconciling heaven and earth and giving a place and a name to the human faculties that can cope with this wide vision.

To reconcile so great a span as heaven and earth is beyond our ordinary way of seeing; generally, two irreconcilable opposites (guilt and need) make neurotic structures in us. It takes a poet—or the poet in us—to overlap such a pair and make a sublime whole of them. Who but Shakespeare could bring the airy nothing of heaven into consonance with the heavy reality of earth and give it a form that ordinary humans can understand? Who but the Shakespeare in yourself?

Take this and take that—and make a mandorla of them.

In your own poetic struggles you may make only the tiniest sliver of a mandorla that will vanish a few minutes later. Where is the inspiration of yesterday that was so thrilling? But if you repeat this often enough it will become the permanent base of your functioning. It can be hoped that by the end of your life the two circles will be entirely overlapped. When one is truly a citizen of both worlds, heaven and earth are no longer antagonistic to each other. Finally one sees that there was only one circle all the time. This is the true fulfillment of the Christian goal, the beatific vision so prized in medieval theology. The two circles were only the optical illusion of our capacity—and need—to see things double.

Mandorla making is not confined to verbal form. An artist makes a mandorla with form, color, visual tension. A musician does the same with rhythm, form, and tone.

Since music is a developed faculty in me, I am aware of the mandorla in this mode more than any other. There is a wonderful moment about three-quarters of the way through Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. The scene is the crucifixion and an alto is singing the solo “Lord Jesus Stretches Forth His Hand.” The alto voice weaves its serene vocal line while a contra fagotto, a particularly rough instrument in the lower register, makes a series of leaps of the natural seventh. This interval (an octave minus one note) is forbidden in classical counterpoint since it resembles the braying of a donkey to a startling degree. Ferde Grofé makes dramatic use of this in his Grand Canyon Suite to portray donkeys going down the canyon trails.* But Bach, in his genius, weaves these two elements together—the most serene and the most ragged and disjointed—and makes a mandorla of it. The serene alto voice goes its tranquil way while the contra fagotto makes a grotesque buffoonery of the natural seventh leap in the bass line. The two together make a sublime whole. It is one of the most healing experiences in the world for me to listen to this moment of genius. If these two extremes can be woven together to make a masterpiece, perhaps I can bring the ragged, disjointed elements of my own life together.

A particularly powerful form of mandorla can be seen in the customs of South American curanderos, who are a curious mixture of primitive shaman and Catholic priest. Their mesa (table) is an altar where they say Mass for the healing of their patients. They divide this altar into three distinct sections. The right is made up of inspiring elements such as a statue of a saint, a flower, a magic talisman; the left contains very dark and forbidding elements such as weapons, knives, or other instruments of destruction. The space between these two opposing elements is a place of healing. The message is unmistakable; our own healing proceeds from that overlap of what we call good and evil, light and dark. It is not that the light element alone does the healing; the place where light and dark begin to touch is where miracles arise. This middle place is a mandorla.*

A mandorla can also be danced. I remember one woman who danced out the conflicting elements in her psyche in her analytical hour. She would portray one part of her life, then move to the opposite side of the room to portray another. This is not familiar ground for me and I was cowering behind my chair by the end of the hour. When finished, she would invite me out of hiding and explain to me what she had been saying in body language.

The criticism may be made that the mandorla is only a private experience and totally divorced from practicality. But the I Ching, in hexagram #61, says, “If a wise man abides in his room his thoughts are heard for more than a thousand miles.” If one makes mandorla in the privacy of his interior life, it is heard for more than a thousand miles.

If you find a person who is particularly peaceful or has a healing presence around her, it is probably because she has done her mandorla work. If you want to affect your environment, don’t get lost in your activism. Stop for a moment and make a mandorla. Don’t just do—be something.

People often asked Dr. Jung , “Will we make it?” referring to the cataclysm of our time. He always replied, “If enough people will do their inner work.” This soul work is the one thing that will pull us through any emergency. The mandorla is peace-making.

I think the loveliest lines in our Scripture are, “If thy eye be single, thy whole body shall be filled with light” (Matt. 6:22). The right eye sees this, the left eye sees that; but if one comes to the third eye, the single eye, all will be filled with light. Indian people put a spot of rouge in the center of the forehead to indicate that they are enlightened (or on the way to enlightenment). In the system of chakras that is the highest point attainable by human consciousness. One more chakra, the seventh, exists, but that is beyond our ordinary ability to experience.

Encouraged by Christian practice, most Westerners invest the energy that might go into a mandorla in useless guilt. Guilt is a total waste of time and energy. I used to tease my Baptist grandmother, telling her guilt was a sin. She would get very angry since I was depriving her of her favorite pastime. She thought she was not doing her duty to Jesus if she were not wringing her hands in guilt at her (or my) sinful condition. Guilt creates nothing; conscious work constructs a mandorla and is healing. The mandorla has no place for remorse. It asks conscious work of us, not self-indulgence.

Guilt is also a cheap substitute for paradox. The energy consumed by guilt would be far better invested in the courageous act of looking at two sets of truths that have collided in our personality. Guilt is also arrogant because it means we have taken sides in an issue and are sure that we are right. While this one-sidedness may be part of the cultural process, it is severely detrimental to the religious life. To lose the power of confrontation is to lose one’s chance at unity—and to miss the healing power of the mandorla.

It is good to remember that the old symbol for Christ—the two lines indicating a stylized fish—is a mandorla. By definition, Christ himself is the intersection of the divine and the human. He is the prototype for the reconciliation of opposites and our guide out of the realm of conflict and duality. Early Christians would make themselves known to one another in this way: upon meeting, one would scratch a small circle in the dust. The other would make a second circle that was slightly overlapping—thus completing a mandorla. This way of greeting—at a time when Christians were severely persecuted—was powerful and eloquent. It also has meaning for us today. If one has a statement to make, it is good to invite another statement—generally one coming from the shadow—and thus make a mandorla that is greater than either point of view alone.

I remember in high school debating class, our teacher once made us change our positions one minute before the debate. I was in a panic for a moment, then felt the flood of energy that came from getting the overview in a new and different way. Indeed, this experience was so powerful that I won the debate. I think I have won (or superseded) some very serious spiritual debates in my inner life by giving credence to both sides, until a superior point of view could be achieved.

The Human Dimensions of the Mandorla

One can view a human life as a mandorla and as the ground upon which the opposites find their reconciliation. In this way every human being is a redeemer, and Christ is the prototype for this human task. Every glance between a man and a woman is also a mandorla, a place where the great opposites of masculinity and femininity meet and honor one another. The mandorla is the divine container in which a new creation begins to form and germinate. Scripture never tires of speaking about courtship and marriage as the symbol for our reconciliation with the spirit. Toni Sussman, a Jungian analyst in London and one of my early teachers, once told me that sex is the one symbol in dreams that is always creative. Even if it occurs in violent form in a dream, still, it is speaking to us of reconciliation and creation. Such is the high place of union in the symbolic world. (This is always true inwardly but cannot be presumed outwardly.)

If we have a powerful mandorla experience (and what a joy it is!), we can be sure it will be brief. We must then return to the world of dualities, of time and space, to continue our ordinary life. The shadow is created all over again, and a new experience of transformation is required. The great individuals in history have only momentary glimpses of wholeness and they, too, return very quickly to the world of ego-shadow confrontation. There is a Hindu proverb: “Anyone who thinks he is enlightened certainly is not!”

Our human situation divides us over and over again into ego-shadow opposition, no matter where we start. This is probably why St. Augustine said, “To act is to sin.” As long as we take our place in society, we will pay for it by bearing a shadow. And society will pay a general price with collective phenomena such as war, violence, and racism. This is why the religious life speaks of another realm, heaven, and of the millennium, as the culmination of the inner life. Culture and religion have different aims.

To balance out our cultural indoctrination, we need to do our shadow work on a daily basis. The first reward for this is that we diminish the shadow we impose on others. We contribute less to the general darkness of the world and do not add to the collective shadow that fuels war and strife. But the second result is that we prepare the way for the mandorla—that high vision of beauty and wholeness that is the great prize of human consciousness.

The ancient alchemists understood this process. In alchemy one goes through four stages of development: the nigredo, in which one experiences the darkness and depression of life; the albedo, in which one sees the brightness of things; the rubedo, where one discovers passion; and finally the citrino, where one appreciates the goldenness of life. After all this comes a full-color mandorla. This is the pavanis, the peacock’s tail that contains all the preceding hues. One cannot stop this process until one has brought it to the pavanis, that concert of colors that contains everything.

Wrongly done, the many colors of life produce a grayness, and all the colors neutralize each other into a dull monotony. Correctly done, the pavanis comes and all the colors of life make a magnificent and rich pattern. The mandorla is not the place of neutrality or compromise; it is the place of the peacock’s tail and rainbows.

Here is some AI generated material that I think is also useful in its own way:

The word "Mandorla" is derived from the Italian word for almond, and it is often used to refer to the shape of the almond itself. In art, the Mandorla is often depicted as a halo or aura surrounding a figure, and is typically used to represent holiness, divine presence, or spiritual enlightenment.

One of the earliest known uses of the Mandorla as a symbol can be traced back to ancient Egypt, where it was used to represent the union of the sun and the moon. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the sun and the moon were often seen as opposing forces, with the sun representing masculine energy and the moon representing feminine energy. The Mandorla, as the union of these two opposing forces, was seen as a symbol of balance and harmony.

The Mandorla also has a long history in Christianity, where it is often used to represent the union of the divine and the human. In Christian art, the Mandorla is often depicted surrounding the figure of Jesus, representing his divine nature. It is also used to represent the union of the Virgin Mary with the divine, as well as the union of the saints with God.

Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology, had a number of interesting thoughts on the Mandorla, particularly in relation to the concept of the Self in his theory of the psyche.

In Jung's view, the Mandorla represented the unity of the Self, which he saw as the integration of all the opposing or complementary elements within the psyche. He believed that the process of individuation, or the journey towards self-realization and wholeness, involved the integration of these opposing elements and the creation of a new, more comprehensive and balanced psyche.

Jung saw the Mandorla as a symbol of this integration and unity, and he believed that it represented the ultimate goal of individuation. He wrote extensively about the symbolism of the Mandorla in his work, and he saw it as a powerful and important symbol for understanding the process of personal growth and development.

Jung also saw the Mandorla as a symbol of the union of the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche. He believed that the integration of these two opposing forces was essential for achieving a healthy and balanced psyche, and he saw the Mandorla as a representation of this integration.

In addition to its symbolic meaning, Jung also saw the Mandorla as a powerful and transformative experience in itself. He believed that the experience of being in the Mandorla, or of merging with it, could be a deeply transformative and spiritual experience that could lead to a deeper understanding of oneself and the world.

References:

"Mandorla." Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mandorla

"The Mandorla in Christian Art." Christian History Institute. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.christianhistoryinstitute.org/study/module/mandorla/

"The Meaning and Symbolism of the Mandorla." My Modern Met. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.mymodernmet.com/the-meaning-and-symbolism-of-the-mandorla/

Jung, C.G. (1969). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. New York: Pantheon Books.

Jung, C.G. (1977). Man and His Symbols. New York: Dell Publishing.

"The Mandorla in Jungian Psychology." Jungian Center for the Spiritual Sciences. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.jungiancenter.org/the-mandorla-in-jungian-psychology/

Also by Robert A. Johnson:

He: Understanding Masculine Psychology

She: Understanding Feminine Psychology

We: Understanding the Psychology of Romantic Love

Inner Work: Using Dreams and Active Imagination for Personal Growth

Ecstasy: Understanding the Psychology of Joy

Femininity Lost and Regained

Transformation: Understanding the Three Levels of Masculine Consciousness

Thank you for reading this Substack.

Please consider a small paid subscription (donation). The money goes to a good cause.

I am always looking for good, personal GMC (pandemic and jab) or childhood vaccination stories. Shared stories are remembered and help others.

In the comments, please let me know what’s on your mind.

You can write to me privately: unbekoming@outlook.com

If you are Covid-jab injured, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment

If you want to understand and “see” what baseline human health looks like, watch this 21 minutes.

Here are three eBooks I have produced so far:

FREE eBook: A letter to my two adult kids - Vaccines and the free spike protein

This work is definitely needed on a global scale. I have witnessed said dance and dancer that made me want to hide behind a chair as well! Excellent writing. I truly appreciate your thoughtful stacks. Always a delight.

👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏💯💯👍😍🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏

Your best stack yet!!! Thank you for listening to the inspiration to write this, it is and will be very much needed in the future.

As an eclectic childhood, with a wonderful but damaged mother- constantly seeking refuge in various religions of the world, i have experienced most of the different main dogmas. None and yet all, incorporate this understanding of mandorlas, although often too subtly discussed (imop). We are both light and dark, heaven and earth, when we are in balance. As above, so below.

Your piece is fantastically written because it breaks down the true power of healing, into less complicated concepts. There have been others that have done the same through the far simpler, modern psychotherapy phrase, "deal with your own $#!@ first."😉 But your explanation is more detailed😉

My personal favourite for the modern interpretation is Ice-Ts, "Check yourself, before your wreck yourself!". But I'm a simple creature😉🤣😂 thank you again for writing this piece, it's reminded me of much loved concepts, and Merry Christmas.😊