The story of polio is the story of pesticides and the cover-up of their effect on humans.

If you are wondering what they were trying to kill, well, one of the very early answers was the potato beetle, and the pesticide of choice was Paris green which is such a lovely name given for arsenic. Yes, they sprayed arsenic on crops, we ate those crops, then they played ignorant for decades about the ensuing paralysis. Thankfully they had a patsy virus to blame. Viruses are wonderful things, mainly because “viruses cannot be sued”.

Maready in his wonderful book The Moth in the Iron Lung, tells the whole story better than anyone else I have come across. Here I have “deboned” his book with all the main references to Paris green.

The problem with Paris green was that it was not “sticky” enough, it would easily wash away, so a clever scientist added lead to the mix and that fixed that. We now had a “sticky” arsenic solution. You will see shortly that I’m not making this up, I’m not that clever.

I was explaining to my wife this morning that the only time I was really stunned by the fact I was lied to was when I discovered that HIV/AIDS as I was told the story was one big fiction, from The Real Anthony Fauci. Ever since that concussion, my fascination in going back into history is not to find out whether I was lied to, I’ve accepted that once a liar, always a liar. That’s what liars do; they lie.

Instead, my fascination is with HOW they do it, the same way I am fascinated by magic tricks. It’s the genius in each of the magic tricks that enthrals me, and how some magic tricks combine a sequence of techniques to achieve the end result. Magic tricks work, they work for a reason, because the fundamental ideas they rely on take advantage of a broad range of human heuristics. It’s the same with The Science, except their magic is done on a global scale.

I find understanding their strategies and tactics to be fascinating. Every one of The Science’s magic tricks is slightly different but as you come to understand enough of them you see what the fundamentals are such as patsy viruses, changing definitions and a whole host of statistical trickery (I’m looking at you relative risk vs absolute risk!).

With thanks to Forrest Maready.

Paris green

The gypsy moth eggs had hatched at 27 Myrtle Street. They had emerged as caterpillars and were scouring the giant oak trees that surrounded the property for food. While this was happening, another insect invasion was fanning across the country, this time from west to east. The potato beetle, or Leptinotarsa decemlineata, is a roundish yellow insect with ten black stripes that run down its back. Its natural habitat had long been the Western United States and Mexico, but in the 1800s as settlers moved across the country, the cultivated potato they brought with them provided a new source of food, and the beetle was able to expand its range eastward.

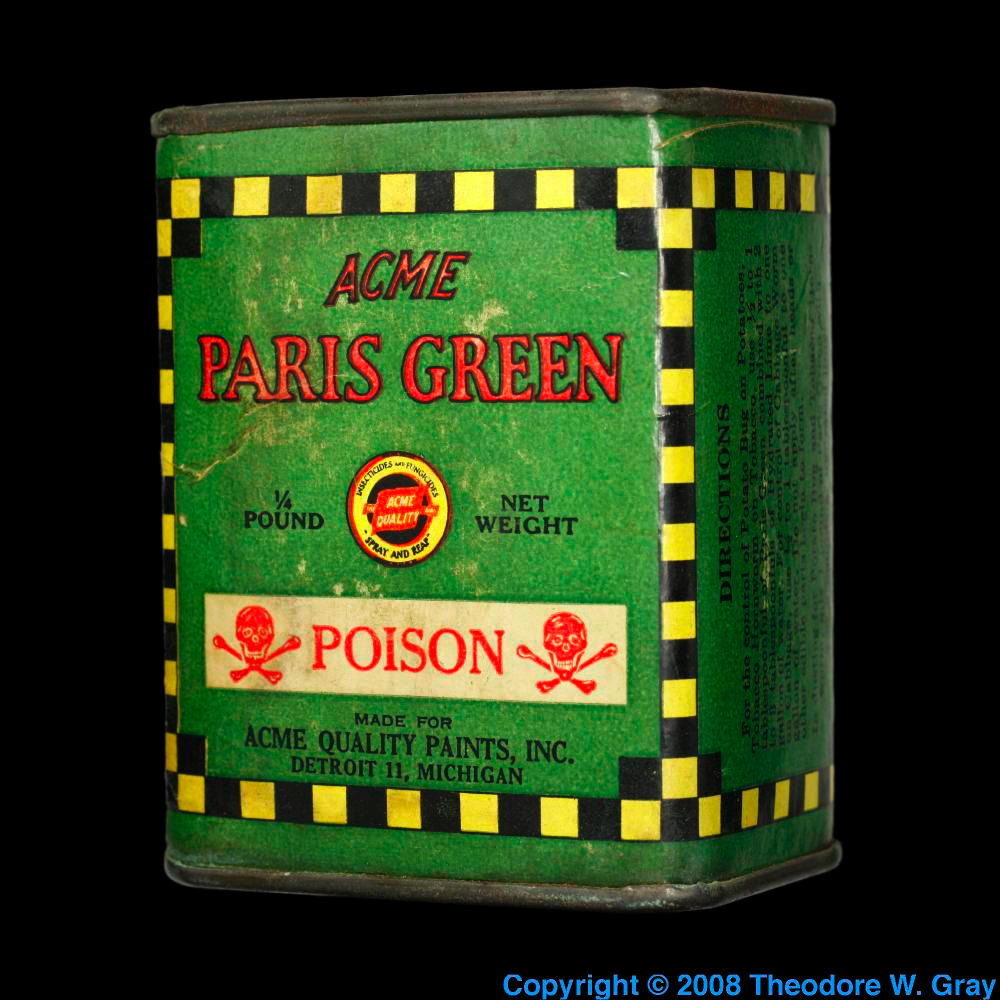

Its steady march seemed unstoppable and, by 1869, the voracious insect had reached Ohio. In a desperate attempt to halt its progress, a new pesticide called Paris green was employed. Paris green was an arsenic-based pigment that had been developed in the early 1800s to great acclaim.

You will notice that the Wikipedia article on Paris Green (or as Liam Scheff calls it, The CIA Factbook) has no mention of Polio.

At that time, there were few options for painters, clothiers, or anyone else who wanted to make something green, so the brilliant emerald hue was tremendously popular and began being used for wallpapers, fabric, toys, and even occasionally, food.

Although it was a favored medicinal ingredient, arsenic had long been known as toxic. Why its use in coloring consumer goods was thought to be safe is unclear, but as a consequence, 19th century literature is replete with stories of death due to poisonings—both accidental and otherwise—from the green color dye and the arsenic it contained. As safer tints arrived on the market, Paris green began to be sold as a powerful pesticide, and its toxicity was thoroughly put to use when the steadfast Potato Beetle began its trek across the country.

Despite the danger of spraying a toxic chemical like arsenic directly onto produce to be consumed by humans, aggressive campaigns to control the potato beetle were undertaken. There was a problem with its application. Paris green, whether dusted onto plants in powder form or sprayed onto them in liquid form, would not adhere to the leaves—the slightest bit of rain or even dew could wash it off. This meant the leaves would only be protected so long as an application stayed dry. And to compound the problem, repeated coatings tended to burn the leaves, ruining the crop they were trying to defend. Striking the right balance between protection from the beetles and destroying the plant—especially when conducted over thousands and thousands of acres—became an impossible task.

By 1874, the potato beetle had reached the Atlantic Coast. Apparently, Paris green had followed with it because a few years later an ominous bit of research was presented at the New York Academy of Medicine by a prominent neurologist, E. C. Seguin. Although the topic had been studied before, he felt compelled to address a growing problem: paralysis following arsenic poisoning. Seguin spent considerable time providing obscure references within the medical literature about the phenomenon, noting a familiar theme:

“In lead paralysis the forearms are usually affected (sometimes only one) arsenical paralysis tends to involve all the limbs ; the lower limbs are more affected…”

Ingested arsenic could occasionally inflame the bowels enough to kill, but it was his recounting of Popov—a Russian scientist who had conducted thorough studies of arsenic poisoning in animals—that should have given anyone listening pause. The results of the post-mortem spinal cord analyses made it clear what was happening:

”Arsenic, even in a few hours after its ingestion, may cause distinct lesions of the spinal cord, of the type known as acute central myelitis, or acute poliomyelitis.”

It wasn’t just scientists that had noticed. Articles and letters from concerned farmers began to appear in agricultural journals like Insect Life and The Country Gentlemen.

Thanks for Nos. 1 and 2 of “Insect Life.” Your publications are great public educators and special aids to farmers… A more thorough knowledge of our friends and foes among insects and birds would increase our farm products. We hope you may find out insecticides which are less dangerous to humanity than arsenic. Two cases of serious illness, but not fatal, have occurred in our neighborhood—one from eating strawberries planted alternately with potatoes which had been dusted with Paris green, and the other from eating raspberries adjoining the potato patch, from which the poison had blown. We hope that Congress will make all necessary appropriations for the carrying on of the good work.—[R. Bingham, Camden, N. J., September 22, 1888.

REPLY.—* * * I am glad to get the account of the two cases of poisoning from the treatment of potatoes by Paris green, and agree with you that a less dangerous remedy would be good. With proper care, however, there is very little danger, and in both the instances which you mention the application was evidently very carelessly made.—[September 25, 1888.]

The arsenic of Paris green may have caused isolated incidents of poisoning—possibly even paralysis—as the potato beetle filed towards the eastern seaboard, but in the confusion of that time, the ability for the ingested poison to paralyze was lost on all but the most astute physicians.

The powerful toxicity of the emerald pesticide was considered its strength.

Its weaknesses, however, would need to be addressed, and soon—they desperately needed something that would adhere to what it was sprayed on, something that couldn’t easily be washed off. The gypsy moths were much hardier than the beetle, and it wasn’t the leaves of the potato—resting safely underground—they were after.

Boston, 1889

The number of caterpillars which attacked Medford that summer defied belief. As its citizens scoured every square inch of their property, trying to strip the hundreds of spongy brown egg masses coating nearly every vertical surface they could see, they realized their efforts would not be enough. There would not be another Blizzard of 1888 for almost one hundred years, and although the authorities began spraying Paris green aggressively, even that would not be sufficient to stop the gypsy moth’s advance.

Boston, 1892

It was a Sisyphean task even Paris green seemed unable to stop. Arsenic is normally toxic by ingestion. Although contact with skin could poison in some circumstances, its effect as a pesticide worked when the food source of the targeted creature —typically leaves—contained enough of the poison to kill. Whether caterpillars had become immune to its effects, or there were simply too many of them was widely debated. Even after throwing caution to the wind and dousing trees with enough Paris green sure to burn their leaves, the insects carried on, unabated.

By 1892, the moths covered an area over 200 square miles. A “Gypsy Moth Commission” had been formed, and men were hired to work full-time in attempts to control the insect’s advance. Police inspected vehicles leaving the area for hitchhiking pests, and the spraying of Paris green increased, despite its apparent futility. A chemist, employed by the commission to develop an insecticide more formidable than Paris green, stumbled onto a new formulation: the arsenic remained, but a new component was added—lead.

The new mixture—dubbed lead arsenate—appeared promising. It was toxic to the caterpillars—that was paramount. Where repeated coatings of Paris green seemed to have little effect on them, lead arsenate killed more readily. It mixed more easily into water and didn’t require constant stirring, making its application in the field less troublesome. After it was applied, it left a translucent white coating, allowing operators to determine which areas had already been treated. The foliage to which it was applied seemed to tolerate repeated spraying. A single application of Paris green to fragile foliage might produce “shot holes” in the leaves, but lead arsenate seldom appeared to cause this effect. Somehow, despite the addition of lead, it was gentler to the leaves on which it was sprayed.

The most important trait—besides its increased toxicity—was met with elation by those under attack from the gypsy moth. It was sticky. It clung to that which it was applied and might remain even after a torrential downpour. Lead arsenate had everything one might want in a pesticide. It was a bit more expensive than Paris green, but the ability to use less could make for a better long term investment. Despite its cost, lead arsenate would prove to be a powerful tool in the fight against the gypsy moth. Its negative effects on other living creatures, however—particularly humans—would take decades to register.

Throughout 1892, word spread quickly about the promise of a miraculous new pesticide. Many who’d ignored the earlier warnings of the gypsy moth had already lost everything, but those who lived nearby clearly saw the destruction they could impose. No amount of Paris green or manual disposal appeared to have any effect on the insect’s proliferation. The mood was dire, but lead arsenate appeared to offer them a weapon with which they might win.

Vermont, 1894

It was spring in 1894. Arsenic poisoning was on many people’s minds due to an increasing number of deaths from an unlikely source—wallpaper.

While those who pointed towards the arsenic often contained within the green dyes of many wall coverings were often ridiculed, other physicians, who had seen the ill effects from living in rooms with this particular kind of wallpaper, began to speak up about its dangers. A chemistry professor from Boston’s Harvard University had been measuring urine specimens for signs of arsenic when an especially acute case appeared. This man, who was excreting high amounts of arsenic, did not appear to have any exposure to the usual sources of the metal.

Because he was also excreting significant amounts of copper, the professor suspected Paris green the likely source and said, “We may have, in the free use of Paris green in the field and garden, one explanation of the frequent occurrence of arsenic in the system.” While the pesticide had undoubtedly caused health problems in many, it was but a prelude to what would happen later that year to residents of Rutland, Vermont—a small town in the western part of the state. Nestled in a valley between two mountain ranges, Rutland is perforated by a rambling stream of water—Otter Creek—that flows northwards into Lake Champlain.

---

While the gypsy moth was making steady gains, it would be a few years before it reached Vermont. Regardless, many in the state were ecstatic about news of a more effective pesticide because they had their own pest to deal with—the codling moth. While not as voracious as their gypsy moth brethren, the codling moth’s cuisine was decidedly more personal to many in New England. They didn’t prefer leaves as much as they did the fruit itself—particularly pears and apples—a diet which gave the moth its nickname, the “appleworm.”

Shortly after winter, local farmers would begin to ready themselves for a long spring of tilling, planting and protecting their crops from the many invaders that could threaten their livelihood. The frequent—and often times unsuccessful—applications of Paris green left much to be desired.

---

In Vermont, however, it wasn’t trees that needed protection so much as food—fruits and vegetables that were planted in spring and harvested throughout the summer. Lead arsenate appeared to be much more toxic than Paris green and would inevitably be sprayed directly onto produce meant for human consumption. The poliomyelitis that physicians had seen in Boston the previous summer was but a prelude.

Within months, Charles Caverly, a physician and President of the Vermont State Board of Health began hearing accounts from his colleagues of unexplainable “acute nervous disease” in the children of Rutland. More concerning—it was accompanied by paralysis. Throughout the summer and into fall, more reports of illness trickled into his office. By the time he had compiled them all and published his findings in the Yale Medical Journal, 123 people would be stricken by this new illness and eighteen of them would die—many of them children.

The outbreak of nervous disease and paralysis in 1894 Rutland, Vermont, is widely considered to be the first epidemic of polio in the United States. A careful examination of the details regarding those who were stricken suggests the answer is more complex.

Spray, O Spray

It was 1914 and the wonders of lead arsenate mesmerized those who grew food for a living. Everyone was encouraged to coat their fruits and vegetables with the wonder pesticide. Farmers who didn't were frowned upon by their neighbors—perhaps an early harbinger of the epidemiologist's favorite construct, herd immunity. By the end of the 19th century, many states had passed laws that required farmers to spray their cops with pesticides. If for some reason they were unable to, they would need to pay to have it done. Additional penalties were employed for farmers caught transporting invasive species within the food they sold.

That’s so interesting.

The spraying of pesticides to kills bugs, as a matter of “public health” is something that you need to do “for the greater good” something that “protects your neighbour, not just you”. Maready is right, the responsibility to spray your own farm to kill bugs that might “infect” other farms, was clearly an early plank in the “herd immunity” paradigm. Doing something to “your property” to protect “someone else’s property” was a precursor to doing something to “your body” to protect “someone else’s body”.

Entomologists of the day—formerly thought of as grown men running through fields with butterfly nets—were no doubt thrilled with their recently discovered power and authority. Lead arsenate was now a mandatory application, and the economic costs of runaway invasive species such as the gypsy or codling moths were beginning to be understood.

A hymn to the newfound riches to be had with the new pesticide may have not been necessary, but nevertheless, this paean likely provided confidence to any farmer that may have doubted the safety of his chemical applications:

Spray, farmers, spray with care,

Spray the apple, peach and pear;

Spray for scar, and spray for blight,

Spray, O spray, and do it right.

Spray the scale that’s hiding there,

Give the insect all a share;

Let your fruit be smooth and bright,

Spray, O spray, and do it right.

Spray your grapes, spray them well,

Make first class what you’ve to sell,

The very best is none too good,

You can have it, if you would.

Spray your roses, for the slug,

Spray the fat potato bug;

Spray your cantaloupes, spray them thin,

You must fight if you would win.

Spray for blight, and spray for rot,

Take good care of what you’ve got;

Spray, farmers, spray with care,

Spray, O spray the buglets there.

And so spray they did. No pest—invasive or not—was safe. Everything was treated with liberal amounts of lead arsenate. Many farmers still turning rows with plow and mule spent their hard earned money not on a mechanical tractor but instead, a mechanical sprayer from which they could drench their produce. As this new pesticide became the go-to method of insect control, Paris green would begin to be marketed as rat poison—an interesting application considering it had been dusted liberally on fruits and vegetables for years.

Although the sticky quality of lead arsenate worked as advertised, overzealous farmers would augment its adhesive nature by adding casein or oil, turning it into a gummy substance that was unlikely to be removed by anything—rain or man. Studies would later confirm this as comparisons between apples that had been sprayed two days previous and two months previous showed little appreciable difference in the amount of arsenic they contained.

At the same time, spraying technology improved, and the cost of lead arsenate began to go down. Farmers rejoiced at their increased productivity, and customers were no doubt elated at the beautiful “fruit, smooth and bright.” With the admonition to “Spray, O Spray” coming at them from every angle, it’s little wonder that much of the nation’s food supply became contaminated with potentially harmful amounts of arsenic and lead.

Reports of children killed by arsenic poisoning began to surface, and authorities—who had worked tirelessly to enforce the mandatory application of pesticides—blamed the deaths on improper spraying techniques by reckless farmers. Scientists financed through agricultural funding wrote thinly-veiled puff pieces for the wonders of lead arsenate.

Remember that…

The goal of corrupted, Junk Science, is to manufacture doubt, in order to stall for time before the product is eventually banned. This industrial defence strategy can be effective for decades.

Others made bold claims about the hundreds of apples one would have to eat in order to become poisoned. J.W. Summers, a congressman and physician—from the apple-friendly state of Washington—boasted that no one could produce an “acute or chronic case of arsenic poisoning resulting from the use of apples or pears.”

The battle for public opinion over the safety of lead arsenate began to play out in newspapers and magazine articles throughout the country.

Because arsenic was still being used as a popular medicinal treatment, it was difficult for whistleblowers to argue that consuming even lesser amounts on food was more dangerous. A little known study was published around that time that might’ve changed people’s minds.

---

Although the 1894 Vermont epidemic was the first poliomyelitis outbreak in the United States, a few others had already occurred in rural areas of Sweden—the birthplace of lead arsenate’s close cousin, Paris green. The fact that the only two countries in the late 1800s experiencing epidemics of poliomyelitis were both heavily employing native-born pesticides suggests that perhaps a rogue enterovirus was not the problem.

---

An obvious question arises: Was Etienne Trouvelot and his escaped gypsy moths responsible for the emergence of poliomyelitis? The question should focus on epidemic poliomyelitis, as isolated cases of infantile paralysis, teething paralysis, and debility of the lower limbs had been occurring for decades.

Paris green had existed long before potato beetles began their eastward trek across the United States. Its transformation from ubiquitous color dye into widespread pesticide was likely inevitable. Lead arsenate, however, was the direct result of the gypsy moth invasion in Massachusetts. It is tempting to suppose the gust of wind in Trouvelot’s kitchen window—had it blown inward, instead of outward—may have kept the gypsy moth egg masses under his control and the subsequent development of lead arsenate out of the diet of children around the world. Perhaps without this fortuitous sequence of events, the large epidemics of poliomyelitis—and the iron lungs that eventually accompanied them—would have never occurred.

In reality, not only would epidemic poliomyelitis have begun to occur anyway, it could have been much worse. Other invasive species were arriving frequently—some of them more harmful than the gypsy moth.

Lead arsenate began to be used en masse, not because it was perfect, but because it worked significantly better than the existing option—Paris green.

Other formulations would have continued to be tried, and in fact, the deadly insecticidal properties of DDT—first synthesized in 1874—may have been discovered in the 1892 quest to stop the gypsy moth, almost fifty years earlier. Where that path would have lead us is difficult to imagine.

The gypsy moth, the codling moth, and all of the other invasive species which had been fought so doggedly by generations of farmers continue to thrive—their legacy not only visible in the disturbed ecosystems they leave in their wake, but the withered limbs and wheelchairs which still dot the country. The pesticides created in hopes of their demise—Paris green, lead arsenate, DDT, and many others—can also be found in museums, rusty cans of poison, their skull and crossbone warnings no longer ignored.

One hundred years later, the toxic assault of lead arsenate remains, as the parents of children living in neighborhoods built on top of old apple orchards can attest. The promise of DDT continues to enchant public health officials, who occasionally suggest its prohibition be lifted to battle the imagined threats of Ebola or Zika. Like war-sick military veterans, they yearn for the good ‘ole days of Flying Flit guns and fogging trucks, billowing plumes of pesticides over pastures and throughout neighborhoods. They would do well to understand the danger goes far beyond runny noses and disrupted bird populations.

The last testament to the era of poliomyelitis—the iron lung—still remains, albeit in a much different form. The mechanical breathers and steel coffins of old have been replaced with unobtrusive masks, their operation nearly silent. Although they could opt for respiration outside the machine, the last few victims of poliomyelitis have chosen to remain in their iron lungs for the rest of their lives—an understandable decision given the relationship which no doubt has formed between man and the machine that has kept them alive for decades.

---

Britton, M.D., W.E. Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin 157. Lead Arsenate and Paris Green. 1907.

E. C. Seguin, M. D., “Myelitis Following Acute Arsenical Poisoning (By Paris Green or Schwein-Furth Green),” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, vol. IX, no. 4 (October 1882)

“Danger to Human Beings from Use of Paris Green,” Insect Life, vol. 1, (1888)

James Putnam and Edward Wyllys Taylor, “Is Acute Poliomyelitis Unusually Prevalent This Season?” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. CXXIX, no. 21, 1893

E. C. Seguin, M. D., “Myelitis Following Acute Arsenical Poisoning (By Paris Green or Schwein-Furth Green),” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, vol. IX, no. 4 (October 1882)

Thank you for reading this Substack.

Please consider a small paid subscription (donation). The money goes to a good cause.

I am always looking for good, personal GMC (pandemic and jab) or childhood vaccination stories. Shared stories are remembered and help others.

In the comments, please let me know what’s on your mind.

You can write to me privately: unbekoming@outlook.com

If you are Covid-jab injured, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment

Here are three eBooks I have produced so far:

FREE eBook: A letter to my two adult kids - Vaccines and the free spike protein

Share this post