It’s not just women, Cartel Medicine feeds on, although it does prefer them.

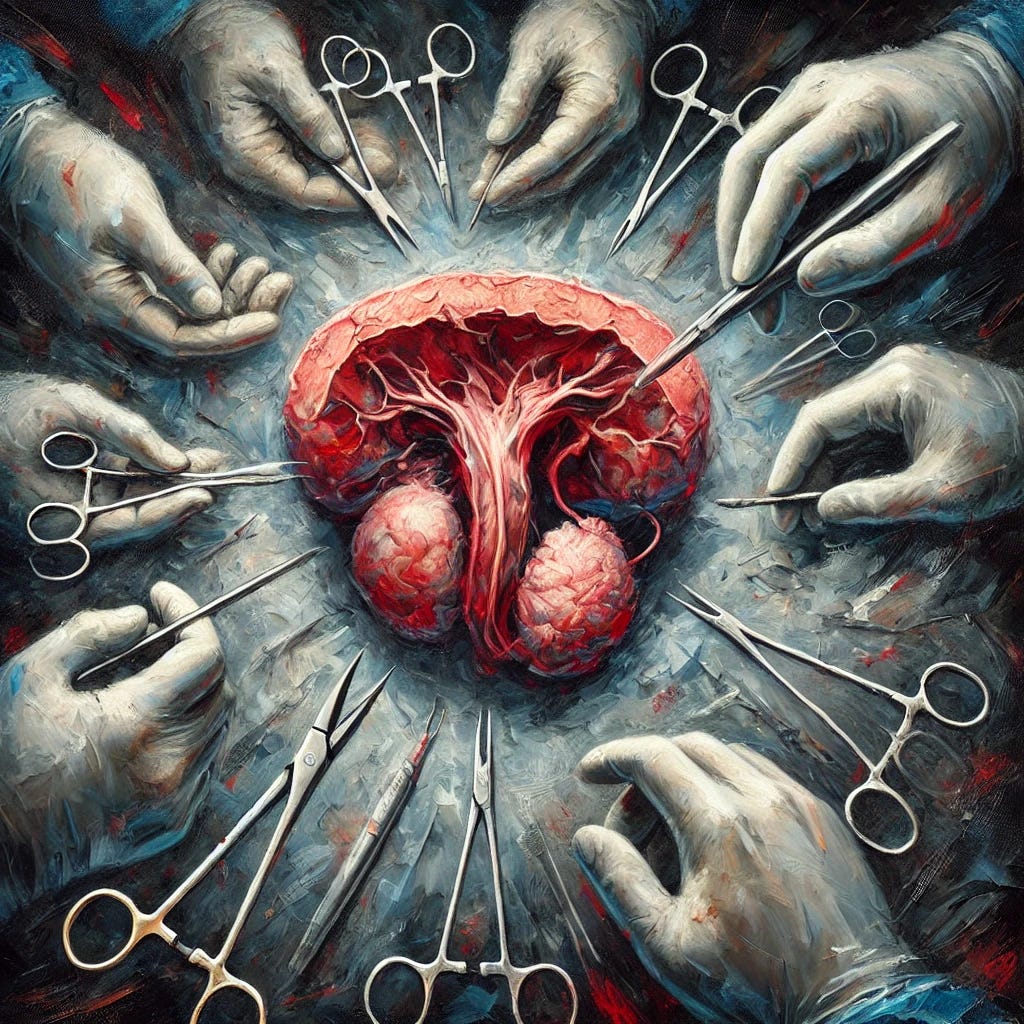

Men are also meat for the grinder, especially when their privates are involved.

The screening hoax we witnessed with mammograms has a counterpart with prostates and the PSA test.

The predation here is especially synergistic as the maiming and destruction caused by prostate interventions feed two sub-Cartels, those of erectile dysfunction and incontinence. The adult diaper business is thriving because of this butchery.

The urologists, not wanting to be left behind by pediatricians, cardiologists, dermatologists and dentists have their own cozy racket.

With thanks to Richard Ablin and Ronald Piana for telling the truth.

Let’s start with an analogy.

Analogy

Imagine you're the owner of a large orchard filled with thousands of apple trees. You know that some of these trees might have a disease that could potentially kill them, but it's rare - only about 3% of your trees will actually die from this disease. The rest will live out their natural lives, disease or not.

Now, a salesman comes to you with a new "revolutionary" test that he claims can detect this disease early. He suggests testing all your trees regularly. It sounds great at first, but there's a catch:

The test often can't tell the difference between healthy trees, trees with harmless spots, and trees with the actual deadly disease. In fact, it's wrong about 80% of the time. When the test says there's a problem, you're forced to cut off large branches from the tree to check if the disease is really there.

For every 1,000 trees you test, you might save one tree from dying of the disease. But in the process, you'll unnecessarily damage hundreds of healthy trees. Many of these trees will never produce apples again, some will be permanently stunted, and a few might even die from the damage caused by your well-intentioned but overzealous pruning.

What's worse, the salesman and the pruning company are making a fortune from all this testing and pruning, which costs you millions every year. They're so invested in this process that they resist any suggestion to change it, even when other orchard experts start to question its value.

This is essentially what's happened with PSA screening for prostate cancer. The test, like our hypothetical orchard test, is often inaccurate. It has led to millions of men undergoing unnecessary biopsies and treatments, which frequently result in life-altering side effects. All of this for a disease that, in most cases, would never have caused them harm. Meanwhile, the medical industry has profited enormously from this process, creating a powerful incentive to maintain the status quo despite mounting evidence of its flaws.

The book's main message is a call to recognize this situation for what it is - a public health disaster driven more by profit than by sound medical science - and to advocate for a more measured, evidence-based approach to prostate cancer detection and treatment.

12-point summary

Here's a 12-point summary of the book, including key data and statistics for those that don’t want to read the longer Q&A below.

PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) is not cancer-specific. It's present in normal, benign, and cancerous prostate tissue. There is no specific PSA level that definitively indicates cancer.

Routine PSA screening leads to significant overdiagnosis and overtreatment. For every 1,000 men screened, only 1 man may avoid death from prostate cancer, while many others suffer unnecessary biopsies and treatments.

Prostate cancer is age-related. About 40% of men aged 40-49, 70% of men 60-69, and 80% of men over 70 have prostate cancer. Most of these cancers are slow-growing and unlikely to cause death.

The lifetime risk of dying from prostate cancer is only 3%, meaning 97% of men will die from other causes, even if they have prostate cancer.

Radical prostatectomy, a common treatment resulting from PSA screening, often leads to significant side effects. Up to 60-80% of men experience erectile dysfunction and 10-20% have long-term urinary incontinence.

PSA screening has not significantly reduced prostate cancer mortality. Studies show similar death rates between screened and unscreened populations.

The PSA test has a high false-positive rate of up to 80%, leading to many unnecessary biopsies and treatments.

Active surveillance is increasingly recognized as an appropriate option for many men with low-risk prostate cancer, potentially avoiding unnecessary treatments and their side effects.

The U.S. healthcare system spends an estimated $3 billion annually on PSA tests alone, with billions more on subsequent procedures and treatments.

New technologies like robotic surgery and proton beam therapy, while heavily marketed, have not shown superior outcomes to traditional treatments but are significantly more expensive.

Conflicts of interest are prevalent in prostate cancer care. Many researchers and physicians promoting PSA screening have financial ties to companies that profit from increased screening and treatment.

The FDA approved the PSA test for screening in 1994 despite significant reservations from its own advisory panel. This decision, along with aggressive marketing by medical companies, led to widespread adoption of PSA screening before its benefits and harms were fully understood.

The Great Prostate Hoax

How Big Medicine Hijacked the PSA Test and Caused a Public Health Disaster

by Richard J. Ablin and Ronald Piana

The Great Prostate Hoax: How Big... book by Richard J. Ablin (thriftbooks.com)

50 Questions & Answers

Question 1: What is PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) and how was it discovered?

PSA, or Prostate-Specific Antigen, is a protein produced by the prostate gland. Its primary function is to liquefy ejaculated semen, allowing sperm cells to swim freely. PSA was discovered in 1970 by Richard J. Ablin during his research at the Millard Fillmore Hospital Research Institute in Buffalo, New York. At the time, Ablin was investigating the effects of cryosurgery on the prostate gland.

Initially, PSA was identified as a prostate tissue-specific antigen, not a cancer-specific marker. This distinction is crucial, as PSA is present in normal, benign, and cancerous prostate tissue. Despite this, PSA later became widely used as a screening tool for prostate cancer, a development that has been the source of much controversy in the medical community.

Question 2: Who is Richard Ablin and what is his role in the PSA story?

Richard J. Ablin is a professor of pathology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, the Arizona Cancer Center, and BIO5 Institute. He is the scientist who discovered PSA in 1970. Since his discovery, Ablin has been a vocal critic of the widespread use of PSA as a screening tool for prostate cancer.

For over three decades, Ablin has publicly denounced mass PSA screening as a public health disaster. He has consistently argued that PSA is not cancer-specific and therefore cannot serve as an accurate test to detect prostate cancer. Despite facing opposition from many in the medical community, Ablin has continued to advocate against routine PSA screening, arguing that it leads to overdiagnosis, unnecessary procedures, and significant harm to men's quality of life.

Question 3: How did PSA testing become a widespread screening tool for prostate cancer?

PSA testing became a widespread screening tool for prostate cancer through a combination of factors, including industry marketing, medical community endorsement, and public health campaigns. After the FDA approved the Hybritech Tandem-R PSA test for monitoring prostate cancer patients in 1986, there was a rapid shift towards using it as a screening tool, despite this not being its approved purpose.

Pharmaceutical companies, particularly Hybritech, saw the potential for a large market in screening healthy men. They aggressively marketed the test, and many urologists quickly adopted it. Public health campaigns, such as Prostate Cancer Awareness Week launched in 1989, further promoted PSA screening. Celebrity endorsements and advocacy groups also played a significant role in popularizing the test. By the early 1990s, PSA screening had become standard practice, despite the lack of evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing prostate cancer mortality.

Question 4: What is the FDA approval process for medical devices like the PSA test?

The FDA approval process for medical devices like the PSA test involves several steps. Devices are classified into three categories based on their potential risk. Class III devices, which include diagnostic tests like PSA, require the most stringent approval process called premarket approval (PMA).

For PMA, manufacturers must submit clinical trial data to support the device's claimed purpose. An FDA advisory committee, composed of experts in the field, reviews the data and makes a recommendation. The FDA then makes a final decision on approval. However, the book highlights that this process can be influenced by various factors, including industry pressure and conflicts of interest. In the case of the PSA test, the advisory panel expressed significant concerns about its effectiveness and potential for harm, yet it was still approved, first for monitoring in 1986 and later for screening in 1994.

Question 5: How did Hybritech develop and market the PSA test?

Hybritech, a biotechnology startup founded in San Diego in 1978, developed the PSA test using monoclonal antibody technology. The company initially sought to create a diagnostic test as a stepping stone to entering the more lucrative cancer therapeutics market. They licensed the PSA antigen from Roswell Park Cancer Institute and developed the Hybritech Tandem-R PSA assay.

Although the test was initially approved only for monitoring men already diagnosed with prostate cancer, Hybritech and other companies quickly began marketing it for widespread screening. They promoted the test through medical conferences, direct marketing to physicians, and public awareness campaigns. The company's aggressive marketing, combined with the medical community's enthusiasm for early cancer detection, led to rapid adoption of PSA screening, despite the lack of evidence for its effectiveness in reducing prostate cancer mortality.

Question 6: What role did William Catalona play in promoting PSA screening?

William J. Catalona, a prominent urologist, played a significant role in promoting PSA screening. He was one of the earliest and most influential advocates for using PSA as a screening tool for prostate cancer. Catalona conducted research on PSA screening and presented data to the FDA in support of approving the test for early detection of prostate cancer.

Catalona argued strongly for routine PSA screening, even recommending lowering the PSA threshold for biopsy from 4.0 ng/mL to 2.5 ng/mL. He used his position as a respected surgeon and researcher to promote PSA screening through medical conferences, publications, and media appearances. Catalona also leveraged his celebrity patients, such as baseball stars Joe Torre and Stan Musial, to promote his message. Despite mounting evidence of the harms associated with widespread PSA screening, Catalona has remained a steadfast supporter of the practice.

Question 7: How do advocacy groups and Prostate Cancer Awareness campaigns influence PSA screening?

Advocacy groups and Prostate Cancer Awareness campaigns have played a significant role in promoting PSA screening. These organizations, often led by prostate cancer survivors, have been instrumental in raising public awareness about prostate cancer and encouraging men to get tested. They organize events, lobby policymakers, and run media campaigns to promote their message.

For example, the Prostate Cancer Awareness Week, launched in 1989, became the nation's largest screening program, growing from about 100 screening centers to more than 1,800 in just three years. These campaigns often use emotional appeals and celebrity endorsements to encourage men to get screened, emphasizing the potential life-saving benefits of early detection while downplaying the risks and limitations of PSA testing. However, critics argue that these campaigns have contributed to overdiagnosis and overtreatment by promoting screening without fully informing men of the potential harms.

Question 8: What impact do celebrity endorsements have on medical practices like PSA screening?

Celebrity endorsements have had a significant impact on promoting PSA screening. Public figures, especially those who have been diagnosed with prostate cancer, often use their platform to encourage other men to get screened. For example, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani publicly advocated for PSA screening after his own diagnosis, citing misleading statistics about survival rates.

These endorsements can be powerful because they put a relatable face on the issue and tap into people's emotions. However, they often oversimplify the complex medical issues surrounding PSA screening. Celebrities typically emphasize their personal experiences of survival without addressing the potential harms of screening or the nuances of interpreting PSA results. This can lead to increased demand for screening among the public, potentially influencing medical practices even when scientific evidence doesn't support widespread screening.

Question 9: How does the PSA test perform in terms of accuracy and false positive rates?

The PSA test has significant limitations in terms of accuracy and false positive rates. It's described as having a false positive rate of up to 80%, meaning that in the majority of cases where the test indicates a potential problem, there is actually no cancer present. This high false positive rate leads to many unnecessary biopsies and treatments.

Moreover, there is no specific PSA level that definitively indicates the presence of cancer. A man can have a low PSA level and have cancer, while another can have a high level and be cancer-free. The test also cannot distinguish between aggressive cancers that need treatment and slow-growing, non-threatening cancers. This lack of specificity contributes to both overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer.

Question 10: What is meant by overdiagnosis and overtreatment in prostate cancer?

Overdiagnosis in prostate cancer refers to the detection of cancers that would never have caused symptoms or death in a man's lifetime. This often occurs with slow-growing or non-aggressive cancers that are common in older men but may never progress to cause harm. PSA screening has led to a significant increase in such diagnoses.

Overtreatment follows overdiagnosis when these non-threatening cancers are treated aggressively. Many men undergo radical prostatectomies, radiation therapy, or other treatments that carry significant risks and side effects, for cancers that would never have affected their health. This results in unnecessary suffering and complications, such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction, without providing a survival benefit. The book argues that this overdiagnosis and overtreatment constitute a public health disaster, causing harm to millions of men.

Question 11: What are the main treatment options for prostate cancer?

The main treatment options for prostate cancer include radical prostatectomy (surgical removal of the prostate), radiation therapy, and active surveillance. Radical prostatectomy can be performed as traditional open surgery or using robotic-assisted laparoscopic techniques. Radiation therapy options include external beam radiation and brachytherapy (internal radiation).

For men with advanced prostate cancer, hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy) is often used. In recent years, immunotherapies like Provenge have also been developed. However, the book emphasizes that many men, especially those with low-risk, slow-growing cancers, may not need immediate treatment. Active surveillance, where the cancer is closely monitored without immediate intervention, is increasingly recognized as an appropriate option for many men.

Question 12: What is a radical prostatectomy and what are its potential side effects?

A radical prostatectomy is a surgical procedure to remove the entire prostate gland and some surrounding tissue. It's one of the primary treatments for localized prostate cancer. The surgery can be performed as an open procedure or using minimally invasive techniques, including robotic-assisted surgery.

The potential side effects of radical prostatectomy are significant and can greatly impact a man's quality of life. The two most common and distressing side effects are urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. These occur because the surgery can damage the nerves and muscles that control urination and erection. Other potential side effects include changes in penis size, difficulty achieving orgasm, and inguinal hernia. The book emphasizes that these side effects can be long-lasting or permanent, significantly affecting a man's sense of well-being and masculinity.

Question 13: How do incontinence and erectile dysfunction affect men after prostate cancer treatment?

Incontinence and erectile dysfunction are two of the most common and distressing side effects of prostate cancer treatment, particularly radical prostatectomy. Urinary incontinence can range from mild leakage to complete loss of bladder control. This can significantly impact a man's daily life, causing embarrassment, social isolation, and the need to use absorbent pads or diapers.

Erectile dysfunction after prostate cancer treatment can be severe and long-lasting. Many men find themselves unable to achieve or maintain erections sufficient for sexual intercourse. This can profoundly affect a man's sense of masculinity, self-esteem, and intimate relationships. The book includes several personal accounts of men struggling with these side effects, highlighting the emotional and psychological toll they can take. While treatments exist for both conditions, they are not always effective and can be costly.

Question 14: What is active surveillance or "watchful waiting" for prostate cancer?

Active surveillance, also known as "watchful waiting," is an approach to managing low-risk prostate cancer without immediate treatment. Instead of rushing to surgery or radiation therapy, men under active surveillance have their cancer closely monitored through regular PSA tests, digital rectal exams, and periodic biopsies.

The goal of active surveillance is to avoid or delay the side effects of aggressive treatments in men whose cancer is unlikely to progress or cause symptoms. This approach recognizes that many prostate cancers grow very slowly and may never become life-threatening, especially in older men. The book argues that active surveillance is an underutilized option that could prevent many unnecessary treatments and their associated side effects. However, it also notes that many men find it psychologically challenging to live with a cancer diagnosis without active treatment.

Question 15: How does age factor into prostate cancer prevalence and treatment decisions?

Age is a crucial factor in both the prevalence of prostate cancer and treatment decisions. The book notes that prostate cancer is primarily a disease of aging. About 40% of men between 40 and 49 have prostate cancer, rising to nearly 70% in men between 60 and 69, and about 80% in men over 70.

Given this high prevalence in older men, age significantly influences treatment decisions. For older men, especially those with other health conditions, the risks of aggressive treatment may outweigh the potential benefits. The slow-growing nature of many prostate cancers means that older men are more likely to die with prostate cancer rather than from it. Despite this, the book criticizes the practice of routinely screening and treating older men, arguing that it often leads to unnecessary interventions that reduce quality of life without extending lifespan.

Question 16: What is the Gleason score and how is it used in prostate cancer diagnosis?

The Gleason score is a grading system used to determine the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. It was developed by pathologist Donald Gleason and has become the standard method for assessing prostate cancer. The score is calculated by examining prostate cancer cells under a microscope and assigning a grade from 1 to 5 based on how abnormal the cells appear compared to normal prostate tissue.

The Gleason score is actually the sum of the two most predominant patterns of cancer cells, resulting in a score from 2 to 10. Scores of 6 or less are considered low grade, 7 is intermediate, and 8 to 10 are high grade. The book points out that while the Gleason score is widely used, it has limitations. It's subjective and can be affected by various factors, including the skill of the pathologist. Moreover, the book argues that even low Gleason scores (like 6) are often treated aggressively, despite evidence that such cancers may not require immediate intervention.

Question 17: What are the prostate cancer mortality rates and how have they changed over time?

Prostate cancer mortality rates have been a subject of much debate and interpretation. The book notes that about 30,000 American men die from prostate cancer each year. However, it's crucial to understand this number in context. While prostate cancer is common, especially in older men, the vast majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer will not die from it.

The introduction of PSA screening in the late 1980s led to a dramatic increase in prostate cancer diagnoses. However, the book argues that this increase in diagnoses has not translated into a significant reduction in prostate cancer deaths. Instead, it has led to the detection and treatment of many cancers that would never have caused symptoms or death. Ablin & Piana contend that claims of reduced mortality due to PSA screening are often based on misleading interpretations of statistics, such as five-year survival rates, which can be inflated by lead-time bias and overdiagnosis.

Question 18: What is lead-time bias and how does it affect interpretation of cancer survival statistics?

Lead-time bias is a statistical phenomenon that can create the illusion of improved survival rates without actually extending lives. In the context of prostate cancer screening, lead-time bias occurs when a cancer is detected earlier through screening, but the patient doesn't actually live any longer than they would have without screening.

For example, if a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 60 through PSA screening and dies at 70, his survival time appears to be 10 years. However, if the same man had not been screened and only diagnosed when symptoms appeared at age 68, then died at 70, his survival time would appear to be only 2 years. The screening didn't extend his life, but it made the survival time appear longer. The book argues that this lead-time bias has led to misinterpretation of prostate cancer statistics, creating an illusion of benefit from PSA screening when in reality, it may not be extending lives.

Question 19: How do racial disparities manifest in prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment?

Racial disparities in prostate cancer are a significant issue, particularly affecting African American men. The book notes that black men have a prostate cancer death rate two to three times higher than their white counterparts. This disparity has been used as an argument for more aggressive PSA screening in the African American community.

However, the book also points out that this approach is controversial. While earlier detection through screening might seem beneficial, it can also lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment, potentially causing more harm than good. Ablin & Piana argues that addressing these disparities requires a more nuanced approach that considers not just screening, but also access to healthcare, socioeconomic factors, and potential biological differences in prostate cancer progression among different racial groups.

Question 20: What role do primary care physicians play in cancer screening decisions?

Primary care physicians play a crucial role in cancer screening decisions, often serving as the first point of contact for patients considering PSA screening. The book emphasizes that these doctors are in a challenging position. On one hand, they are expected to follow guidelines and provide evidence-based care. On the other hand, they face pressures from patients, advocacy groups, and sometimes their own training to recommend screening.

Ablin & Piana argues that many primary care physicians have been performing PSA tests routinely, often without fully discussing the potential risks and benefits with patients. This practice has contributed to overscreening and overdiagnosis. The book calls for a more informed, shared decision-making process between doctors and patients, where the complexities and potential harms of PSA screening are fully explained. However, it also acknowledges the time constraints and other pressures that can make such in-depth discussions challenging in a typical primary care setting.

Question 21: How has the US Preventive Services Task Force influenced PSA screening recommendations?

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has played a significant role in shaping PSA screening recommendations. In 2012, the USPSTF issued a recommendation against routine PSA screening for healthy men of all ages, citing evidence that the potential harms outweigh the benefits. This recommendation was based on large-scale studies showing that PSA screening resulted in little to no reduction in prostate cancer mortality while leading to significant overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

The USPSTF's recommendation caused significant controversy and backlash from urological groups and prostate cancer advocates. However, the book argues that the USPSTF's stance was evidence-based and courageous, given the entrenched interests supporting PSA screening. Ablin & Piana notes that the USPSTF's recommendation has slowly begun to shift medical practice, although resistance from pro-screening groups remains strong.

Question 22: What is the concept of shared decision-making in healthcare and how does it apply to PSA screening?

Shared decision-making is a process where patients and healthcare providers work together to make healthcare decisions based on clinical evidence and patient preferences. In the context of PSA screening, shared decision-making involves a thorough discussion of the potential benefits and risks of screening, allowing the patient to make an informed choice.

The book argues that true shared decision-making has been largely absent in PSA screening. Many men have been routinely screened without being fully informed of the potential harms, such as false positives, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment. Ablin & Piana advocates for a more transparent approach where doctors explain the complexities of PSA screening, including the high rate of false positives and the potential for unnecessary treatments. However, the book also acknowledges the challenges in implementing shared decision-making, including time constraints in clinical practice and the difficulty of conveying complex medical information to patients.

Question 23: How have medical journals shaped clinical practice regarding PSA screening?

Medical journals have played a crucial role in shaping clinical practice regarding PSA screening, often with conflicting effects. On one hand, journals have published numerous studies highlighting the limitations and potential harms of PSA screening. These include large-scale trials showing little to no mortality benefit from screening and studies documenting the negative impacts of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

On the other hand, the book argues that many journals have also contributed to the promotion of PSA screening by publishing studies with flawed methodologies or biased interpretations. Ablin & Piana cites instances where industry-funded research promoting PSA screening has been given prominence in respected journals. Furthermore, the book contends that the slow pace of publication and the tendency to favor positive results have sometimes delayed the dissemination of critical information about the harms of PSA screening.

Question 24: What are some of the conflicts of interest present in medical research and practice related to PSA?

The book highlights numerous conflicts of interest in medical research and practice related to PSA screening. Many researchers and physicians promoting PSA screening have financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers, or treatment centers that profit from increased screening and subsequent treatments. For example, some prominent urologists advocating for PSA screening have received consulting fees or research funding from companies producing PSA tests or prostate cancer treatments.

Ablin & Piana also points out conflicts of interest in professional organizations like the American Urological Association, which has financial incentives to promote procedures resulting from PSA screening. Additionally, the book discusses how some advocacy groups promoting PSA screening receive funding from companies with a vested interest in increased screening. These conflicts of interest, Ablin & Piana argues, have led to biased research, skewed public health messages, and resistance to changing practices even in the face of evidence showing harms from routine PSA screening.

Question 25: How has the medical industry profited from PSA screening and prostate cancer treatment?

The book argues that the medical industry has profited enormously from PSA screening and subsequent prostate cancer treatments. The widespread adoption of PSA screening created a massive market for testing kits, biopsies, and treatments. Pharmaceutical companies, medical device manufacturers, and healthcare providers have all benefited financially from this trend.

For instance, Ablin & Piana notes that routine PSA screening leads to over a million prostate biopsies annually in the United States, each costing thousands of dollars. This is followed by numerous radical prostatectomies, radiation treatments, and other interventions, all of which are highly profitable for hospitals and physicians. The book also discusses how the industry has capitalized on treatment side effects, creating markets for products addressing incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Ablin & Piana contend that this profit motive has been a significant factor in the continued promotion of PSA screening despite evidence of its limitations and harms.

Question 26: What is "gizmo idolatry" and how does it apply to prostate cancer treatment?

"Gizmo idolatry" refers to the tendency in medicine to embrace new, high-tech treatments or devices without sufficient evidence of their superiority over existing methods. In prostate cancer treatment, this concept is exemplified by the rapid adoption of technologies like robotic surgery and proton beam therapy.

The book discusses how these expensive technologies have been aggressively marketed and widely adopted, despite lacking clear evidence of improved outcomes compared to traditional treatments. For instance, robotic-assisted prostatectomy, which costs significantly more than traditional surgery, has not been shown to result in better cancer control or fewer side effects. Similarly, proton beam therapy, requiring massive, billion-dollar facilities, has not demonstrated superior results to conventional radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Ablin & Piana argues that this "gizmo idolatry" has contributed to escalating healthcare costs without proportional improvements in patient outcomes.

Question 27: How do proton beam therapy and robotic surgery factor into the economics of prostate cancer treatment?

Proton beam therapy and robotic surgery represent significant economic factors in prostate cancer treatment, illustrating the high costs associated with new technologies. Proton beam therapy centers cost hundreds of millions of dollars to build and require a steady stream of patients to be financially viable. The book notes that these centers often rely heavily on prostate cancer patients to recoup their investments, despite lacking evidence of superior outcomes compared to conventional radiation therapy.

Similarly, robotic surgery systems like the da Vinci Surgical System cost millions of dollars to purchase and maintain. Hospitals investing in these systems have a strong financial incentive to use them frequently, potentially influencing treatment recommendations. Ablin & Piana argues that these expensive technologies have contributed to the rising costs of prostate cancer treatment without clear evidence of improved patient outcomes. This economic pressure, they contend, has led to the overuse of these technologies and resistance to changing practices even when evidence suggests they may not be necessary or superior to less expensive alternatives.

Question 28: What are some alternative treatments for prostate cancer, such as cryosurgery?

The book discusses several alternative treatments for prostate cancer, with a particular focus on cryosurgery. Cryosurgery, also known as cryotherapy or cryoablation, involves freezing the prostate gland to destroy cancer cells. Ablin & Piana's personal experience with cryosurgery in treating his father's prostate cancer is described, highlighting both the potential benefits and risks of this approach.

Other alternative treatments mentioned include high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) and various forms of immunotherapy. The book also discusses emerging research into treatments that aim to harness the body's immune system to fight cancer, such as the use of dendritic cells. However, Ablin & Piana emphasizes that many of these alternative treatments, while promising, still lack robust evidence of long-term efficacy and safety. He argues for more research into these alternatives, particularly those that might offer effective treatment with fewer side effects than traditional approaches.

[Unbekoming: See Q37 in German Cancer Therapies.]

Question 29: What is immunotherapy and how is it being explored for prostate cancer treatment?

Immunotherapy is an approach to cancer treatment that aims to stimulate or support the body's own immune system to fight cancer cells. In the context of prostate cancer, the book discusses several immunotherapy approaches, including the FDA-approved treatment Provenge (sipuleucel-T).

Provenge is a personalized treatment that involves extracting a patient's immune cells, exposing them to a protein found on prostate cancer cells, and then reinfusing them into the patient. The goal is to train the immune system to recognize and attack prostate cancer cells. The book also mentions ongoing research into other immunotherapy approaches, such as cancer vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors.

However, Ablin & Piana also highlights controversies surrounding immunotherapy treatments like Provenge, including questions about their efficacy, high costs, and potential conflicts of interest in their development and promotion. He argues for continued research into immunotherapy while cautioning against premature adoption of treatments without solid evidence of their effectiveness and safety.

Question 30: How have pharmaceutical and medical device companies influenced prostate cancer screening and treatment?

The book argues that pharmaceutical and medical device companies have had a profound influence on prostate cancer screening and treatment, often prioritizing profit over patient benefit. These companies have aggressively marketed PSA tests, surgical robots, and various treatments, sometimes overstating benefits and downplaying risks.

For instance, Ablin & Piana describes how Hybritech, the company that developed the first FDA-approved PSA test, rapidly shifted from promoting it as a monitoring tool to marketing it for widespread screening, despite lacking evidence of its effectiveness in reducing mortality. Similarly, companies producing robotic surgical systems have promoted their use for prostatectomies, despite limited evidence of superior outcomes compared to traditional surgery.

The book also discusses how these companies have funded research, influenced medical education, and lobbied policymakers to promote their products. Ablin & Piana contend that this corporate influence has contributed to overdiagnosis and overtreatment in prostate cancer, prioritizing financial gains over patient well-being and evidence-based medicine.

Question 31: What role has the National Cancer Institute played in prostate cancer research and policy?

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has played a significant role in prostate cancer research and policy, but the book suggests its impact has been mixed. As the primary federal agency for cancer research, the NCI has funded numerous studies on prostate cancer, including research on PSA screening and treatment effectiveness.

However, Ablin & Piana argues that the NCI has not been as proactive as it could have been in addressing the overuse of PSA screening. The book notes that despite mounting evidence of the harms of routine PSA screening, the NCI was slow to challenge the status quo. Ablin & Piana suggests that political pressures and the influence of pro-screening advocates may have affected the NCI's stance on this issue.

Question 32: How have government health agencies like the FDA, NIH, and CDC responded to concerns about PSA screening?

The book paints a critical picture of how government health agencies have responded to concerns about PSA screening. The FDA, in particular, is criticized for approving the PSA test for screening purposes in 1994 despite significant reservations from its own advisory panel. Ablin & Piana argues that the FDA failed to adequately monitor the off-label use of PSA tests and did not take sufficient action when evidence of harm emerged.

The NIH and CDC are portrayed as being slow to challenge the widespread use of PSA screening. While these agencies eventually acknowledged the limitations and potential harms of routine screening, the book suggests that their responses were often too late and too weak to significantly impact clinical practice. Ablin & Piana contend that these agencies should have taken a more proactive role in educating the public and medical community about the risks of overscreening and overtreatment.

Question 33: What are some examples of regulatory failures related to PSA screening?

The book highlights several regulatory failures related to PSA screening, with the FDA's actions (or lack thereof) being a primary focus. One major failure was the FDA's approval of the PSA test for screening purposes in 1994, despite significant concerns raised by its own advisory panel about the test's effectiveness and potential for harm.

Another regulatory failure discussed is the lack of effective oversight of off-label use of PSA tests. Ablin & Piana notes that even before the FDA approved PSA for screening, it was being widely used for this purpose. Despite this clear violation of regulations, the FDA took little action to curb this practice. The book argues that these regulatory failures allowed the unchecked proliferation of PSA screening, leading to widespread overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer.

Question 34: How has off-label use of medical tests and devices affected PSA screening practices?

Off-label use of medical tests and devices has significantly impacted PSA screening practices. The book describes how PSA tests, initially approved only for monitoring men already diagnosed with prostate cancer, were quickly and widely adopted for screening healthy men. This off-label use occurred with little oversight or intervention from regulatory bodies.

Ablin & Piana argues that this off-label use of PSA tests has been a major driver of overscreening and overdiagnosis in prostate cancer. It allowed the practice of routine PSA screening to become entrenched in medical practice before there was sufficient evidence of its benefits or harms. The book contends that the medical industry's promotion of off-label PSA screening, coupled with regulatory inaction, has led to millions of men undergoing unnecessary tests and treatments.

Question 35: What is the psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment?

The psychological impact of a prostate cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment is profound, according to the book. Men often experience intense fear and anxiety upon hearing the word "cancer," which can lead to rushed decision-making about treatment. Ablin & Piana describes how the fear of cancer can override rational consideration of the risks and benefits of different management approaches.

Moreover, the book discusses the long-term psychological effects of prostate cancer treatment. Many men struggle with changes to their sense of masculinity and self-esteem, particularly when dealing with side effects like incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Ablin & Piana argues that these psychological impacts are often underappreciated in discussions about PSA screening and prostate cancer treatment, yet they significantly affect men's quality of life.

Question 36: How have patient experiences and testimonials shaped the PSA screening debate?

Patient experiences and testimonials have played a significant role in shaping the PSA screening debate, often in favor of screening. The book describes how prostate cancer survivors, particularly those who believe their lives were saved by PSA screening, have become powerful advocates for routine testing. These personal stories, often emotional and compelling, have been used effectively in public awareness campaigns and lobbying efforts.

However, Ablin & Piana argues that these testimonials can be misleading. While individual stories of survival are powerful, they don't necessarily reflect the overall impact of PSA screening on the population. The book contends that the voices of men harmed by overdiagnosis and overtreatment are often less heard in public discourse, skewing the perception of PSA screening's value.

Question 37: What are some of the critiques of the U.S. healthcare system highlighted by the PSA controversy?

The PSA controversy, as described in the book, highlights several critiques of the U.S. healthcare system. One major criticism is the system's tendency to adopt new tests and treatments without sufficient evidence of their effectiveness or consideration of potential harms. The rapid and widespread adoption of PSA screening is presented as a case study in how financial incentives can drive medical practice more than scientific evidence.

Another critique is the system's difficulty in changing established practices even when evidence shows they may be harmful. The book argues that vested interests, including pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers, and specialist physicians, have resisted changes to PSA screening guidelines despite mounting evidence of its limitations. This resistance is seen as emblematic of broader issues in U.S. healthcare, where profit motives can override patient interests.

Question 38: How have health care costs and resource allocation been affected by widespread PSA screening?

The book argues that widespread PSA screening has had a significant impact on healthcare costs and resource allocation. Ablin & Piana estimates that routine PSA screening costs the U.S. healthcare system billions of dollars annually, not just for the tests themselves, but for the cascade of follow-up procedures and treatments that often result from positive tests.

This expenditure, the book contends, represents a misallocation of healthcare resources. Ablin & Piana argues that the money spent on PSA screening and subsequent unnecessary treatments could be better used for other healthcare needs or for research into more effective prostate cancer detection and treatment methods. The high costs associated with PSA screening are presented as an example of how the U.S. healthcare system often prioritizes expensive interventions over more cost-effective preventive measures.

Question 39: What is evidence-based medicine and how does it contrast with profit-driven practices in healthcare?

Evidence-based medicine is described in the book as an approach to medical practice that emphasizes the use of the best available scientific evidence in making decisions about patient care. This approach involves critically appraising research, considering both the benefits and harms of interventions, and integrating this information with clinical expertise and patient values.

Ablin & Piana contrasts this with profit-driven practices in healthcare, where financial incentives can lead to the adoption and promotion of tests and treatments without adequate evidence of their effectiveness. The PSA screening controversy is presented as a prime example of this conflict, where the profit motive behind promoting widespread screening has often overshadowed the scientific evidence questioning its value. The book argues that truly evidence-based practice in prostate cancer care would likely result in less screening and treatment, but better overall patient outcomes.

Question 40: How has media coverage influenced medical practices related to PSA screening?

Media coverage has played a significant role in shaping public perception and medical practices related to PSA screening, according to the book. Ablin & Piana notes that news stories often focus on the potential benefits of screening, featuring personal stories of men who believe their lives were saved by early detection. This positive coverage has helped create a public perception that PSA screening is universally beneficial.

However, the book also criticizes media coverage for often failing to adequately convey the complexities and potential harms of PSA screening. Ablin & Piana argues that nuanced scientific discussions about the limitations of screening and the risks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment are often oversimplified or omitted in media reports. This has contributed to a public demand for screening that can influence medical practice, even when it may not align with the best available scientific evidence.

Question 41: What are some historical medical practices, like radical mastectomy, that parallel the PSA screening controversy?

The book draws parallels between the PSA screening controversy and historical medical practices like the radical mastectomy. Radical mastectomy, developed by William Stewart Halsted in the late 19th century, involved extensive surgery to remove breast tissue, chest muscles, and lymph nodes. It became the standard treatment for breast cancer for decades, despite its disfiguring effects and lack of evidence for improved survival.

Like PSA screening, radical mastectomy was widely adopted based on the belief that more aggressive intervention was always better. The book argues that both cases demonstrate how medical practices can become entrenched despite lack of evidence, and how difficult it can be to change these practices even when evidence emerges showing they may be harmful or unnecessary.

Question 42: How do medical malpractice concerns influence clinical practice regarding PSA screening?

The book discusses how fear of medical malpractice lawsuits can influence clinical practice regarding PSA screening. Doctors may feel pressured to recommend PSA tests and aggressive treatments out of concern that failing to do so could leave them vulnerable to lawsuits if a patient later develops advanced prostate cancer.

This defensive medicine approach, Ablin & Piana argues, can lead to overscreening and overtreatment. The book cites examples of doctors who changed their practices to include more PSA testing after being involved in malpractice cases, even when they believed this wasn't in the best interest of their patients. This highlights how legal concerns can sometimes override evidence-based medical decision making.

Question 43: What are some of the next-generation prostate cancer tests being developed?

The book discusses several next-generation prostate cancer tests being developed to address the limitations of the PSA test. These include tests that measure different forms of PSA or combine PSA with other biomarkers, aiming to improve specificity and reduce false positives. Examples mentioned include the 4Kscore test and the Prostate Health Index (PHI).

However, Ablin & Piana cautions that while these new tests may offer some improvements, they still face many of the same fundamental issues as PSA testing. The book argues that without a true prostate cancer-specific marker, these tests may still lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Ablin & Piana emphasizes the need for tests that can distinguish between aggressive cancers that need treatment and indolent cancers that can be safely monitored.

Question 44: How has the concept of medical ethics and informed consent evolved in relation to cancer screening?

The book traces the evolution of medical ethics and informed consent in relation to cancer screening, particularly PSA testing. Initially, PSA tests were often performed without full discussion of their potential risks and limitations, based on the assumption that early detection was always beneficial. Ablin & Piana argues that this approach violated the principle of informed consent.

Over time, as evidence of the harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment emerged, there has been a shift towards emphasizing shared decision-making. The book advocates for a more thorough informed consent process for PSA screening, where men are fully informed about both potential benefits and harms before deciding whether to be tested. This evolution reflects a broader trend in medical ethics towards greater patient autonomy and more transparent discussion of medical uncertainties.

Question 45: What public health policies have been implemented or proposed regarding PSA screening?

The book discusses various public health policies regarding PSA screening, noting significant changes over time. Initially, many health organizations recommended routine PSA screening for men over 50. However, as evidence of potential harms emerged, policies began to shift. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force's 2012 recommendation against routine PSA screening for healthy men is highlighted as a major policy change.

Ablin & Piana also discusses policies aimed at improving informed decision-making, such as requiring doctors to have detailed discussions with patients about the pros and cons of PSA screening before ordering the test. However, the book notes that implementation of these policies has been inconsistent, and there remains significant debate about the appropriate role of PSA screening in public health policy.

Question 46: How has statistical interpretation in medical research affected our understanding of PSA screening efficacy?

The book delves into how statistical interpretation in medical research has significantly influenced our understanding of PSA screening efficacy. It discusses concepts like lead-time bias and overdiagnosis, which can create the illusion of improved survival rates without actually extending lives. Ablin & Piana argues that misinterpretation of these statistics has led to overestimation of the benefits of PSA screening.

Furthermore, the book criticizes the use of relative risk reduction rather than absolute risk reduction in reporting study results. This approach, Ablin & Piana contend, can make the benefits of screening appear more substantial than they actually are. The book emphasizes the importance of careful, nuanced interpretation of medical statistics to accurately assess the true impact of PSA screening.

Question 47: What is the concept of "creative destruction" in medical progress and how does it relate to PSA screening?

The book introduces the concept of "creative destruction" in medical progress, borrowed from economic theory. In medicine, this refers to the process by which new discoveries and practices replace older ones, often disrupting established norms. Ablin & Piana suggests that the PSA screening controversy represents a potential moment of creative destruction in prostate cancer care.

The book argues that truly embracing evidence-based medicine might require "destroying" the current paradigm of routine PSA screening and aggressive treatment of all detected cancers. This would involve overcoming significant resistance from those invested in the current approach. However, Ablin & Piana contend that this creative destruction could ultimately lead to better patient outcomes and more efficient use of healthcare resources.

Question 48: How has the role of urologists in promoting PSA screening been perceived and critiqued?

The book presents a critical view of the role urologists have played in promoting PSA screening. It argues that many urologists have been strong advocates for routine screening, often downplaying potential harms and overstating benefits. Ablin & Piana suggests that this advocacy is partly driven by financial incentives, as PSA screening leads to more biopsies and treatments, which are primary sources of income for urologists.

However, the book also notes that the urological community is not monolithic, and some urologists have been vocal critics of routine PSA screening. Ablin & Piana calls for a re-evaluation of the urologist's role, advocating for a more balanced approach that prioritizes patient well-being over financial considerations. The book suggests that urologists should take a leading role in educating patients about the complexities of PSA screening and prostate cancer management.

Question 49: What are some future directions in prostate cancer research and treatment?

The book discusses several promising directions for future prostate cancer research and treatment. One key area is the development of better diagnostic tools that can distinguish between aggressive cancers that need treatment and indolent cancers that can be safely monitored. Ablin & Piana also highlights ongoing research into targeted therapies and immunotherapies that could provide more effective treatment with fewer side effects.

Another important direction is the refinement of active surveillance protocols, allowing more men with low-risk cancers to avoid unnecessary treatment. The book also emphasizes the need for more research into the underlying biology of prostate cancer, which could lead to new prevention strategies. Overall, Ablin & Piana advocates for a research agenda that prioritizes reducing overdiagnosis and overtreatment while improving outcomes for men with aggressive disease.

Question 50: How has the PSA screening controversy impacted overall quality of life for men?

The book argues that the PSA screening controversy has had a significant impact on the quality of life for many men. On one hand, some men believe that PSA screening saved their lives, leading to early detection and treatment of potentially lethal cancers. These men often report a sense of gratitude and improved quality of life due to screening.

On the other hand, Ablin & Piana contend that many men have suffered decreased quality of life due to the side effects of unnecessary treatments resulting from PSA screening. Issues like incontinence and erectile dysfunction can have profound effects on men's physical and emotional well-being. The book also discusses the psychological impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment, even for men whose cancers may never have caused symptoms. Overall, Ablin & Piana argues for a more nuanced approach to prostate cancer care that better balances potential benefits against risks to quality of life.

I appreciate you being here.

If you've found the content interesting, useful and maybe even helpful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While everything here is free, your paid subscription is important as it helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. It also helps keep it free for those that cannot afford to pay.

Please make full use of the Free Libraries.

Unbekoming Interview Library: Great interviews across a spectrum of important topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Concise summaries of important books.

Stories

I'm always in search of good stories, people with valuable expertise and helpful books. Please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com

For COVID vaccine injury

Consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Baseline Human Health

Watch and share this profound 21-minute video to understand and appreciate what health looks like without vaccination.

DREs (digital rectal exams, for those who haven't endured this indignity) are nearly as worthless as colonoscopies. The difference being that learning that you have an enlarged prostate at least tells you why you are peeing more often and having to get up multiple times during the night. Most of what they learn from a colonoscopy they could have told you just based upon your symptoms. But then they don't get paid for each often benign polyp they find...

We have too many friends who have gone the radical prostatectomy route, despite my wife having been during the 90s unofficially dubbed as the "prostate queen of Seattle." They trust their doc, and figure she would only confirm what he advised. So yeah, they're now in that growing cohort of men with adult diapers and erectile dysfunction, when the likelihood is that the cancer would have been slow growing. Most hadn't progressed to the point of having difficulty peeing, which is when it often becomes necessary to do SOMETHING. Just not necessarily a roto-rooter job on the crown jewels.

Her title stemmed from her being the nurse of Dr. John Blasko, who helped pioneer the use of radioactive seed implantation to shrink prostate tumors. His father had died of prostate cancer, so he was on a mission to find a better way to deal with it. Unfortunately, one of the few pots of money available for research comes with the string attached that part of the solution has to include radium. So, he couldn't search for the best solution, only the best solution based upon that insane constraint.

His treatment was superior to blasting the tumor and surrounding tissue with external beam radiation, and had fewer side effects than surgical intervention. But all ANY radiation does is potentially reduce tumor size - it does nothing to stop the disease. That's useful when a cancer has grown to the point of impeding the functioning of an organ and thus being a threat to survival, but it hardly justifies effectively being REQUIRED by standard of care, as part of the barbaric cancer triad of burn, cut and poison.

I haven't done a deep dive on this issue, because the people I've known with it simply won't talk about it.

And they trust that their physicians know more than I ever could. But, if I ever develop prostate cancer, the two things I would try, to at least deal with the difficulty of peeing issue, are oral vitamin C and DMSO applied directly to the penis. Both can help improve urine flow. C presumably by reducing inflammation, and DMSO by the many magical properties that it has.

Virtually all of the allopathic cancer industry is a scam. And the few effective treatments that they offer are done in a way to squeeze every penny out of you.

I read somewhere (I do have the info) that survival rates of cancer, doing absolutely nothing was historically 12 years. Playing with my kids one day, I twirled around and stepped off a low platform deck, just the right way, and broke my foot. Went to hospital by ambulance cause I could not walk. X-rays taken of both feet naturally for comparison, and was told nothing was broken, just a bad sprain. Got a boot and off I went. Black & blue covered my entire foot up my leg with each passing day. Saw an ortho weeks later who refitted my broken foot to pain I had never experienced. Same thing, only worse, happened to my mother who had her broken arm cast, bones in the wrong direction, who had to have her arm rebroken and set again.

Broken bones, on an x-ray, and no doctor could see that? WTF!! If a doctor cannot see a broken bone, why in heavens name, would I ever believe a cancer diagnosis, a Lyme disease diagnosis, a Fibromyalgia or any other algia, itis diagnosis. I am a candidate for every possible screening out there. The doctor who told me that is no longer my doctor. I ran out of there like the building was on fire. I simply do not want to know or be part of their never ending scamming.