I keep being pointed to Ivan Illich. I thought it time to pay attention to his work.

Here from a reader Runemasque:

…Ivan Illich was a Catholic priest who identified the religious elements in a variety of institutions, including most famously medicine (Medical Nemesis, Life as Idol...), and education (Deschooling Society). His influence led to other great thinkers continuing these kinds of exploration. For example, John McKnight (Careless Society, the Abundant Community), and Thomas Szaz (The Manufacture of Madness, about psychiatry).

I would encourage anyone interested in the highlighted pattern overlap of religion and medicine (and extension to other institutions) to look into Ivan Illich. His thinking is so nuanced and insightful that it goes far beyond simply drawing up some plain comparisons…

There is a breadth and depth to Illich’s work that is breathtaking.

Each sentence and paragraph can be read and reread with more extracted each time.

He was telling us about the poisoning.

He was telling us about the new religion.

He was telling us about the tyranny.

He was telling us about the lies.

He was telling us about the predation.

He was telling us about the monster.

He was telling us about today.

He predicted it all.

Medical Monopoly (excerpt from Medical Nemesis)

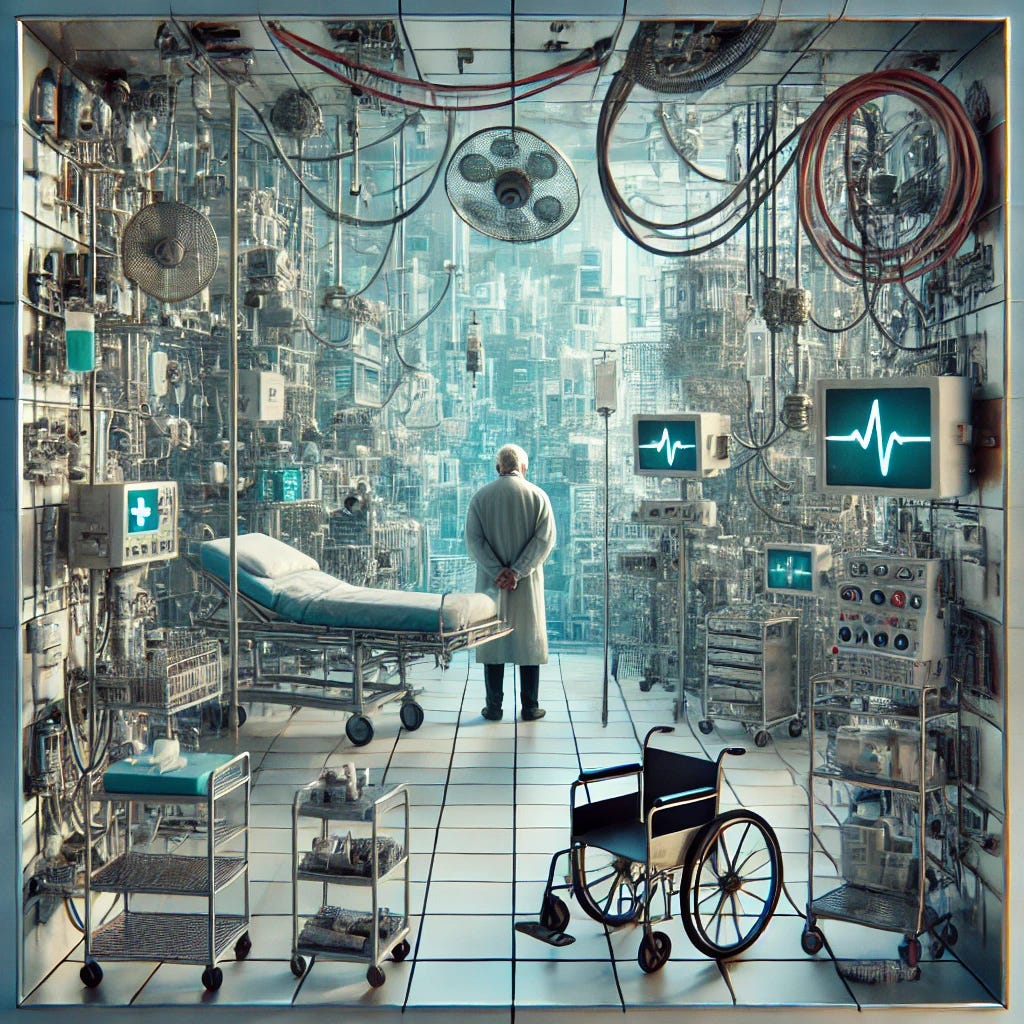

Like its clinical counterpart, social iatrogenesis can escalate from an adventitious feature into an inherent characteristic of the medical system. When the intensity of biomedical intervention crosses a critical threshold, clinical iatrogenesis turns from error, accident, or fault into an incurable perversion of medical practice. In the same way, when professional autonomy degenerates into a radical monopoly8 and people are rendered impotent to cope with their milieu, social iatrogenesis becomes the main product of the medical organization.

A radical monopoly goes deeper than that of any one corporation or any one government. It can take many forms. When cities are built around vehicles, they devalue human feet; when schools pre-empt learning, they devalue the autodidact; when hospitals draft all those who are in critical condition, they impose on society a new form of dying. Ordinary monopolies corner the market;9 radical monopolies disable people from doing or making things on their own. The commercial monopoly restricts the flow of commodities; the more insidious social monopoly paralyzes the output of nonmarketable use-values. Radical monopolies impinge still further on freedom and independence. They impose a society-wide substitution of commodities for use-values by reshaping the milieu and by "appropriating" those of its general characteristics which have enabled people so far to cope on their own. Intensive education turns autodidacts into unemployables, intensive agriculture destroys the subsistence farmer, and the deployment of police undermines the community's self-control. The malignant spread of medicine has comparable results: it turns mutual care and self-medication into misdemeanors or felonies.

Just as clinical iatrogenesis becomes medically incurable when it reaches a critical intensity and then can be reversed only by a decline of the enterprise, so can social iatrogenesis be reversed only by political action that retrenches professional dominance.

A radical monopoly feeds on itself. Iatrogenic medicine reinforces a morbid society in which social control of the population by the medical system turns into a principal economic activity. It serves to legitimize social arrangements into which many people do not fit. It labels the handicapped as unfit and breeds ever new categories of patients. People who are angered, sickened, and impaired by their industrial labor and leisure can escape only into a life under medical supervision and are thereby seduced or disqualified from political struggle for a healthier world.

Social iatrogenesis is not yet accepted as a common etiology of disease. If it were recognized that diagnosis often serves as a means of turning political complaints against the stress of growth into demands for more therapies that are just more of its costly and stressful outputs, the industrial system would lose one of its major defenses. At the same time, awareness of the degree to which iatrogenic ill-health is politically communicated would shake the foundations of medical power much more profoundly than any catalogue of medicine's technical faults.

Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health (1975)

By Ivan Illich

Question 1: What is the central thesis or argument presented by Ivan Illich in "Medical Nemesis"?

In "Medical Nemesis," Ivan Illich argues that the medical establishment has become a major threat to health. He contends that the medicalization of life has led to the expropriation of health, as individuals have become increasingly dependent on medical professionals and institutions for their well-being, leading to a loss of autonomy and the ability to cope with pain, suffering, and death.

Question 2: How does Illich define the concept of iatrogenesis, and what are the three levels at which it occurs?

Illich defines iatrogenesis as the harm done to individuals and society by medical interventions and the medical establishment. He identifies three levels of iatrogenesis: clinical iatrogenesis, which refers to the direct harm caused by medical treatments; social iatrogenesis, which describes the broader impact of medicalization on society; and cultural iatrogenesis, which involves the destruction of traditional ways of dealing with illness, suffering, and death.

Social Iatrogenesis

Medicine undermines health not only through direct aggression against individuals but also through the impact of its social organization on the total milieu. When medical damage to individual health is produced by a sociopolitical mode of transmission, I will speak of "social iatrogenesis," a term designating all impairments to health that are due precisely to those socio-economic transformations which have been made attractive, possible, or necessary by the institutional shape health care has taken.

Question 3: According to Illich, how has the medicalization of life contributed to the expropriation of health?

Illich argues that the medicalization of life has led to the expropriation of health by making individuals dependent on medical professionals and institutions for their well-being. This dependence has undermined people's ability to cope with pain, suffering, and death on their own terms, as well as their autonomy in making decisions about their health.

Question 4: What role does the concept of "natural death" play in Illich's critique of modern medicine?

Illich traces the evolution of the concept of "natural death" in Western culture, arguing that it has been transformed from an accepted part of life to a technical problem to be managed by medical professionals. He contends that this shift has contributed to the medicalization of death and the denial of its inevitability, leading to a loss of autonomy and the ability to face mortality on one's own terms.

Medicine is a moral enterprise and therefore inevitably gives content to good and evil. In every society, medicine, like law and religion, defines what is normal, proper, or desirable. Medicine has the authority to label one man's complaint a legitimate illness, to declare a second man sick though he himself does not complain, and to refuse a third social recognition of his pain, his disability, and even his death. It is medicine which stamps some pain as "merely subjective," some impairment as malingering, and some deaths—though not others—as suicide. The judge determines what is legal and who is guilty. The priest declares what is holy and who has broken a taboo. The physician decides what is a symptom and who is sick. He is a moral entrepreneur, charged with inquisitorial powers to discover certain wrongs to be righted. Medicine, like all crusades, creates a new group of outsiders each time it makes a new diagnosis stick. Morality is as implicit in sickness as it is in crime or in sin.

Question 5: How does Illich characterize the relationship between the medical establishment and the pharmaceutical industry?

Illich describes the close relationship between the medical establishment and the pharmaceutical industry, arguing that doctors have become increasingly reliant on drugs and medical technologies in their practice. He contends that this reliance has led to the overuse and misuse of medications, as well as the creation of new diseases and the medicalization of normal human experiences.

Question 6: What is the significance of the "diagnostic imperialism" described by Illich?

Illich uses the term "diagnostic imperialism" to describe the expansive power of the medical establishment to define and categorize human experiences as medical conditions. He argues that this power has led to the medicalization of a wide range of human behaviors and experiences, from aging to childbirth to sadness, and has contributed to the expropriation of health.

Diagnostic Imperialism

In a medicalized society the influence of physicians extends not only to the purse and the medicine chest but also to the categories to which people are assigned.

Medical bureaucrats subdivide people into those who may drive a car, those who may stay away from work, those who must be locked up, those who may become soldiers, those who may cross borders, cook, or practice prostitution,129 those who may not run for the vice-presidency of the United States, those who are dead, those who are competent to commit a crime, and those who are liable to commit one. On November 5, 1766, the Empress Maria Theresa issued an edict requesting the court physician to certify fitness to undergo torture so as to ensure healthy, i.e. "accurate," testimony; it was one of the first laws to establish mandatory medical certification.

Question 7: How does Illich view the impact of medical technology on the doctor-patient relationship?

Illich argues that the increasing reliance on medical technology has transformed the doctor-patient relationship, reducing it to a technical interaction focused on the management of disease rather than the care of the whole person. He contends that this shift has contributed to the dehumanization of medicine and the erosion of trust between doctors and patients.

Question 8: What are the consequences of the "medicalization of the budget," according to Illich?

Illich describes the "medicalization of the budget" as the increasing proportion of individual and societal resources devoted to medical care. He argues that this trend has led to the neglect of other important social goods, such as education and housing, and has contributed to the rising costs of healthcare without corresponding improvements in health outcomes.

Question 9: How does Illich differentiate between the traditional role of the physician and the modern medical professional?

Illich contrasts the traditional role of the physician as a healer who used empathy, experience, and a holistic approach to care for patients with the modern medical professional who relies on scientific knowledge, technology, and standardized protocols. He argues that the latter approach has led to the depersonalization of medicine and the erosion of the doctor-patient relationship.

The New World Religion - Lies are Unbekoming (substack.com)

“The study of the evolution of disease patterns provides evidence that during the last century doctors have affected epidemics no more profoundly than did priests during earlier times. Epidemics came and went, imprecated by both but touched by neither. They are not modified any more decisively by the rituals performed in medical clinics than by those customary at religious shrines.” - Ivan Illich, in Limits to Medicine

Question 10: What is the connection between the industrialization of society and the rise of iatrogenesis, as described by Illich?

Illich argues that the industrialization of society has contributed to the rise of iatrogenesis by promoting a mechanistic view of the human body and a reliance on technological solutions to health problems. He contends that this approach has led to the neglect of the social, environmental, and cultural factors that shape health, as well as the erosion of traditional ways of coping with illness and suffering.

Question 11: How does Illich characterize the relationship between medical care and social control?

Illich argues that the medical establishment has become a powerful instrument of social control, using its authority to define and manage deviance, disability, and dependency. He contends that this control is exercised through the medicalization of a wide range of human experiences and behaviors, as well as the creation of new categories of illness and treatment.

Ivan Illich (1926-2002) was a gifted polymath who recognized a variety of ills within society and accurately predicted what they would lead to throughout his lifetime and well after his death. One of Illich’s central beliefs was that the complexity necessary to maintain the smooth functioning of an increasingly technologically advanced society would result in the socialist governments of the world seeking to use every technological means available to more and more micromanage each aspect of society. Illich argued these (now laughably primitive) technocratic dictatorships were attempting to fulfill a fundamentally impossible task, and because they failed to recognize this, would instead respond to their failures by seeking more and more control over society.

Illich staunchly opposed our countless manipulative institutions and the elaborate mechanisms of control they utilized to force human beings into compliance. He viewed the reality they sought to create as being in direct opposition to human nature. Instead, Illich believed the ideal form of government followed a more decentralized model that supported or encouraged the natural capacities of each member of society and provided the tools each member needed to succeed (which like many idealists I believe the internet was meant to be a platform for). This thesis was based upon Illich’s observations of how well members of radically different societies around the world were able to work together, innovate, and become highly successful once they were allowed to do so.

In many ways, I realize we are in precisely the world Illich predicted. In turn, the current movement to micromanage every facet of our lives “with data” is being spearheaded by Silicon Valley. Conversely, anyone who wishes to act independently (e.g., by thinking critically) is actively disparaged as we are all told to “Trust the Science.” - A Midwestern Doctor

Question 12: What is the significance of the concept of "specific counterproductivity" in Illich's critique of medicine?

Illich uses the concept of "specific counterproductivity" to describe the phenomenon whereby the pursuit of a specific goal, such as health, through industrial means can actually undermine that goal. He argues that the medicalization of life has led to a form of counterproductivity in which the pursuit of health through medical interventions has actually contributed to the erosion of health and autonomy.

Question 13: How does Illich view the impact of medical education on the perception and treatment of illness?

Illich argues that medical education has contributed to the medicalization of life by promoting a narrow, biomedical view of illness that neglects the social, cultural, and experiential dimensions of health and suffering. He contends that this approach has led to the dehumanization of medicine and the neglect of the patient's lived experience.

Question 14: What are the consequences of the medicalization of aging, according to Illich?

Illich argues that the medicalization of aging has led to the transformation of the elderly into a dependent, medicalized population, subject to increasing levels of professional control and intervention. He contends that this trend has contributed to the erosion of the autonomy and dignity of the elderly, as well as the neglect of their social and emotional needs.

Question 15: How does Illich describe the evolution of the concept of pain in Western medicine?

Illich traces the evolution of the concept of pain in Western medicine, arguing that it has been transformed from a subjective experience to be interpreted and endured to an objective symptom to be diagnosed and treated. He contends that this shift has contributed to the medicalization of suffering and the erosion of the cultural frameworks that traditionally helped individuals to cope with pain.

Question 16: What is the relationship between the "killing of pain" and the loss of cultural frameworks for dealing with suffering?

Illich argues that the "killing of pain" through medical interventions has contributed to the loss of cultural frameworks for dealing with suffering. He contends that the pursuit of a pain-free existence has led to the neglect of the meaning and value of suffering, as well as the erosion of the social and spiritual resources that traditionally helped individuals to cope with pain and adversity.

Question 17: How has the "invention and elimination of disease" contributed to the medicalization of life, according to Illich?

Illich argues that the "invention and elimination of disease" by the medical establishment has contributed to the medicalization of life by expanding the scope of medical authority and intervention. He contends that the creation of new diagnostic categories and the redefinition of normal human experiences as medical conditions have led to the increased dependence on medical professionals and treatments.

Question 18: What is the significance of the changing attitudes towards death in Western culture, as described by Illich?

Illich traces the evolution of attitudes towards death in Western culture, arguing that the medicalization of death has led to the denial of its inevitability and the erosion of the cultural and spiritual frameworks that traditionally helped individuals to confront mortality. He contends that this shift has contributed to the dehumanization of the dying process and the neglect of the social and emotional needs of the dying and their families.

Question 19: How does Illich characterize the impact of "intensive care" on the experience of dying?

Illich argues that the rise of "intensive care" has transformed the experience of dying, subjecting the dying person to increasing levels of technological intervention and professional control. He contends that this trend has contributed to the dehumanization of death and the erosion of the autonomy and dignity of the dying.

Question 20: What are the limitations of consumer protection and equal access as solutions to the problems of iatrogenesis, according to Illich?

Illich argues that consumer protection and equal access to medical care are insufficient solutions to the problems of iatrogenesis, as they fail to address the underlying causes of medicalization and the expropriation of health. He contends that these approaches may actually reinforce the dependence on medical professionals and institutions, rather than promoting autonomy and self-care.

Question 21: How does Illich view the role of professional control and licensing in perpetuating medical iatrogenesis?

Illich argues that professional control and licensing in medicine contribute to the perpetuation of iatrogenesis by reinforcing the authority and dominance of the medical establishment. He contends that these mechanisms limit the ability of individuals to make informed choices about their health and restrict the range of alternative approaches to healing and care.

Question 22: What is the significance of the "scientific organization of life" in Illich's critique of modern medicine?

Illich uses the term "scientific organization of life" to describe the increasing control and management of human life by scientific and technical experts. He argues that this trend has contributed to the medicalization of life and the erosion of individual autonomy and cultural diversity, as well as the neglect of the social and environmental determinants of health.

Question 23: How does Illich define the concept of "health," and how does it differ from the biomedical model?

Illich defines health as the ability to adapt to changing environments, cope with suffering and adversity, and maintain autonomy and responsibility for one's own well-being. This definition differs from the biomedical model, which focuses on the absence of disease and the technical management of bodily functions.

Question 24: What are the characteristics of a society that fosters widespread health, according to Illich?

Illich argues that a society that fosters widespread health is one that promotes autonomy, responsibility, and the equitable distribution of the means of self-care. He contends that such a society would minimize the role of professional medicine and emphasize the importance of social, cultural, and environmental factors in shaping health.

Question 25: How does Illich propose to address the problem of medical nemesis through political and legal means?

Illich proposes several political and legal measures to address the problem of medical nemesis, including the limitation of professional monopolies, the protection of the right to self-care, and the promotion of alternative approaches to health and healing. He also emphasizes the importance of public participation and democratic control over health policies and institutions.

Question 26: What is the relationship between autonomy, responsibility, and health in Illich's view?

Illich argues that autonomy and responsibility are essential components of health, as they enable individuals to make informed choices about their lives and to cope with the challenges and adversities they face. He contends that the medicalization of life has eroded these capacities by promoting dependence on professional expertise and technological interventions.

Question 27: How does Illich characterize the impact of industrialization on traditional cultural frameworks for dealing with illness and suffering?

Illich argues that industrialization has contributed to the erosion of traditional cultural frameworks for dealing with illness and suffering by promoting a mechanistic view of the body and a reliance on technological solutions to health problems. He contends that this trend has led to the neglect of the social, spiritual, and experiential dimensions of health and the loss of cultural diversity in approaches to healing.

Question 28: What is the significance of the concept of "medical nemesis" in Illich's critique of modern medicine?

Illich uses the concept of "medical nemesis" to describe the unintended and harmful consequences of the medicalization of life. He argues that the pursuit of health through industrial medicine has led to a form of cultural and social iatrogenesis that undermines the autonomy, responsibility, and resilience of individuals and communities.

Question 29: How does Illich view the role of myth and ritual in traditional approaches to health and healing?

Illich argues that myth and ritual played an important role in traditional approaches to health and healing by providing individuals with cultural frameworks for interpreting and coping with illness, suffering, and death. He contends that the medicalization of life has led to the erosion of these frameworks and the loss of their therapeutic and integrative functions.

Question 30: What are the implications of Illich's critique for the future of healthcare and the pursuit of health in modern society?

Illich's critique of modern medicine has significant implications for the future of healthcare and the pursuit of health in modern society. It suggests the need for a fundamental reorientation of health policies and practices, emphasizing the importance of autonomy, responsibility, and the social determinants of health, rather than the narrow focus on technological interventions and professional expertise. It also highlights the importance of cultural diversity and the need to preserve and revitalize traditional approaches to health and healing.

Thank You for Being Part of Our Community

Your presence here is greatly valued. If you've found the content interesting and useful, please consider supporting it through a paid subscription. While all our resources are freely available, your subscription plays a vital role. It helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. Please make full use of our Free Libraries.

Discover Our Free Libraries:

Unbekoming Interview Library: Dive into a world of thought-provoking interviews across a spectrum of fascinating topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Explore concise summaries of groundbreaking books, distilled for efficient understanding.

Share Your Story or Nominate Someone to Interview:

I'm always in search of compelling narratives and insightful individuals to feature. Whether it's personal experiences with the vaccination or other medical interventions, or if you know someone whose story and expertise could enlighten our community, I'd love to hear from you. If you have a story to share, insights to offer, or wish to suggest an interviewee who can add significant value to our discussions, please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com. Your contributions and suggestions are invaluable in enriching our understanding and conversation.

Resources for the Community:

For those affected by COVID vaccine injury, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Discover 'Baseline Human Health': Watch and share this insightful 21-minute video to understand and appreciate the foundations of health without vaccination.

Books as Tools: Consider recommending 'Official Stories' by Liam Scheff to someone seeking understanding. Start with a “safe” chapter such as Electricity and Shakespeare and they might find their way to vaccination.

Your support, whether through subscriptions, sharing stories, or spreading knowledge, is what keeps this community thriving. Thank you for being an integral part of this journey.

May 3rd 1957, a school night, my mother sent us all out to the movies. My oldest sister was already married with a 2 year old which left 5 remaining children in house. Dr Eisenhard, an old-timer, came to the house before we all left. We didn't think anything of it because he made house calls all the time when someone got sick or we all came down with measles at the same time.

He was tall, I was little, but I remember him rolling up his sleeves, going to the kitchen to wash up and then touching us all very gently to examine us. There was no such thing as herding all of us into a car for a doctor visit. He came to us. And charged my mother 2 bucks a head. I still drive by his office and his home was right across the street. Beautiful structures. He obviously made money where he could but had enormous empathy for those who had little. He even accepted baked goods for payment. He was the last of his breed in my neck of the woods.

That night we came home from the movies, ran to my mothers room to tell her about the movie, and there she was, my new sister wrapped like a papoose next to Ma. Dr Eisenhard slumped in a chair, looking exhausted, like he did all the work. I never have to think how old my nephew is. He's 2 years OLDER than his aunt. Ain't that a gas.

Invitation: I'm going to put my fantasy out there because, who knows what may come of it. As a lifelong physically isolated "friend" of Illich, I want to reinvoke the friendship tradition of Illich. He was known to use his professorships to enable gatherings of friends where in the spirit (con-spirit-acy) of friendship they would purposefully explore and work on the concepts and issues, the big questions, in need of discussion. The influence of Illich's intellectual salons or conspiracies of friends has furthered ground-breaking intellectual work in so many domains. You have John McKnight, Barbara Duden, David Cayley, Thomas Szasz, Uwe Poerksen, Nils Christie,....

We need to add to these excellent starts that Unbekoming is offering us. We need to dig in to the big questions. What are they? What can we explore and grow of them? Just as much as Illich's definition of health presumes a responsibility and autonomy, so I see that I must limber my life from not just intellectual exposure from the armchair, but to a cultivation of being alive. In the conspiracy of company, there is for us the work we can do for ourselves and with each other, to grow what is fitting for us to grow, to expect a surprise of good which may come.

Anyone?