"When illness is blamed on bacteria, so-called "viruses" and genes, not only are enormous profits generated for the pharmaceutical industry selling their antibiotics, antivirals, vaccines and the myriad of other related drugs, but it also protects the other hand of the same industry that sells herbicides, pesticides, chemical fertilizers, preservatives, etc... as it obscures one of the fundamental causes of illness...our nutrient-deficient and poison laden foods."

- T.C. Fry, Founder of Life Science Institute

The Ebola construction predates AIDS.

They’ve been practicing this racketeering for a long time, making improvements and iterations that culminated with their magnum opus, Covid.

The Ebola racket isn’t discussed enough, so I thought I’d do something about that.

This is long, but if you want to finally come to terms with the Official Story of Ebola™, the content in this stack should help you orient yourself towards it honestly. At least more honestly than the CDC or Hollywood version of the story.

Let’s start first with this recent comment from Allen.

People are "made" ill all the time.

It is most definitely not "clear" at all that anything "spread" through the population in fact there is zero evidence that there was any unusual amount of illness in early 2020 whatsoever. This has morphed into urban legend with zero proof.

Ebola is purely fictional. It's yet another construct of the pandemic industrial complex/biosecurity complex with multiple purposes attached.

Ebola is cover for industrial operations in Africa which produce major pollutants that have no regulations/oversight in Africa—mining, offshore oil exploration and drilling, rubber-tapping, etc.- Firestone rubber plantation- massive water pollution directly into once potable water that the locals still must drink from as there is no other source of drinking water etc.

The locals curiously then get the same symptoms as "Ebola" after drinking the polluted water.

Plus: Insecticides/Banned Pesticide Dumping in Africa, indoor spraying- walls in West African homes coated with insecticides: carbamates and organophosphates are increasingly important alternatives to pyrethroids for indoor residual spraying. Toxic Vaccine Campaigns in Africa- Beta-lactam Antibiotics- Pharma Profiteering etc. Same story in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Congo.

Ebola is the cover story.

Cover for good old colonialism- land theft- scramble for Africa etc. US also uses Ebola/Marburg cover con to justify moving troops into area (AFRICOM) in order to clamp down certain areas- control a restive populace, prevent other competing entities from gaining a foothold on the region etc.

But no, it's all Ebola/Marburg and has nothing to do with oil reserves off the Liberian Coast, diamond mines in Sierra Leone, coltan in the Congo etc...

Same as it ever was.

I strongly recommend listening to this discussion on Ebola between David Crowe and David Rasnick. Especially the last 20 minutes.

Ebola Theater- Fauci's other fraud (rumble.com)

Next, let’s spend some time with Jon Rappaport one of the earliest, maybe even the first, investigative reporters to call out the Ebola racket.

Ebola: shattering the lies and the fakery

Once again, the virus is the cover story

by Jon Rappoport

January 12, 2022

Ebola: shattering the lies and the fakery « Jon Rappoport's Blog (nomorefakenews.com)

We’re warned, now and then, that a new Ebola outbreak might be spreading. It’s one of those Coming Attractions in the theater that shows one virus movie after another.

In this case, the fear-hook is the bleeding symptom. It makes people cower in the dark. O my God, look at the BLOOD. It’s…THE VIRUS.”

Yahoo News, 2/26/21 [1]: “…the World Health Organization reported a cluster of Ebola cases in Guinea…The Biden administration is moving forward with plans to screen airline passengers from two African countries arriving in the U.S. for Ebola…”

Because I do the work others won’t do…and because I covered the Ebola story in 2017 and 2014, here are essential quotes from my pieces during that period—

There is one predictable outcome: at Congo clinics and hospitals, frightened people who arrive with what are labeled “early signs” of Ebola will be diagnosed as probable cases. What are those symptoms? Fever, chill, sore throat, cough, headache, joint pain. Sound familiar? Normally, this would just be called the flu.

The massive campaign to make people believe the Ebola virus can attack at any moment, after the slightest contact, is quite a success.

People are falling all over themselves to raise the level of hysteria.

And that is preventing a hard look at Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the Republic of Guinea, three African nations where poverty and illness are staples of everyday life for the overwhelming number of people.

The command structure in those areas has a single dictum: don’t solve the human problem.

Don’t clean up the contaminated water supplies, don’t return stolen land to the people so they can thrive and grow food and finally achieve nutritional health, don’t solve overcrowding, don’t install basic sanitation, don’t strengthen immune systems, don’t let the people have power—because then they would throw off the local and global corporate juggernauts that are sucking the land of all its resources.

In order not to solve the problems of the people, a cover story is necessary. A cover story that exonerates the power structure.

A cover story like a virus.

It’s all about the virus. The demon. The strange attacker.

Forget everything else. The virus is the single enemy.

Forget the fact, for example, that a recent study of 15 pharmacies and 5 hospital drug dispensaries in Sierra Leone discovered the widespread and unconscionable use of beta-lactam antibiotics.

These drugs are highly toxic. One of their effects? Excessive bleeding.

Which just happens to be the scary “Ebola effect” that’s being trumpeted in the world press.

(J Clin Microbiol, July 2013, 51(7), 2435-2438), and Annals of Internal Medicine Dec. 1986, “Potential for bleeding with the new beta-lactam antibiotics”)

Forget the fact that pesticide companies are notorious for shipping banned toxic pesticides to Africa. One effect of the chemicals? Bleeding.

Forget that. It’s all about the virus and nothing but the virus.

Forget the fact that, for decades, one of the leading causes of death in the Third World has been uncontrolled diarrhea. Electrolytes are drained from the body, and the adult or the baby dies. (Diarrhea is also listed as an “Ebola” symptom.)

Any sane doctor would make it his first order of business to replace electrolytes with simple supplementation—but no, the standard medical line goes this way:

The diarrhea is caused by germs in the intestinal tract, so we must pile on massive amounts of antibiotics to kill the germs.

The drugs kill off all bacteria in the gut, including the necessary and beneficial ones, and the patient can’t absorb what little food he has access to, and he dies.

Along the way, he can also bleed.

But no, all the bleeding comes from Ebola. It’s the virus. Don’t think about anything else.

Forget the fact that adenovirus vaccines, which have been used in Liberia, Guinea, and Liberia (the epicenter of Ebola), have, according to vaccines.gov, the following adverse effects: blood in the urine or stool, and diarrhea.

Reporter Charles Yates uncovered a scandal in Liberia centering around the Firestone Rubber Plantation—chemical dumping, poisoned water.

And skin disease.

“Rash” is listed as one of the Ebola symptoms.

Then there is the Liberia Coca Cola bottling plant: foul black liquid seeping into the environment—animals dying.

Chronic malnutrition and starvation—conditions that are endemic in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea—are the number-one cause of T-cell depletion (aka immune system suppression) in the world.

Getting the picture?

In email correspondence with me, David Rasnick, PhD, announced this shocking finding:

“I have examined in detail the literature on isolation and Ems [EM: electron microscope pictures] of both Ebola and Marburg viruses. I have not found any convincing evidence that Ebola virus (and for that matter Marburg) has been isolated from humans. There is certainly no confirmatory evidence of human isolation.”

In other words, there is no evidence that the Ebola virus actually exists.

Rasnick obtained his PhD from the Georgia Institute of Technology, and spent 25 years working with proteases (a class of enzymes) and protease inhibitors. He is the author of the book, The Chromosomal Imbalance Theory of Cancer. He was a member of the Presidential AIDS Advisory Panel of South Africa.

The real reasons for the “Ebola outbreak” include, but are not limited to: industrial pollution; organophosphate pesticides (causes bleeding); vast overuse of antibiotics (causes bleeding); severe and debilitating nutritional deficiencies (which can cause bleeding); starvation; drastic electrolyte loss; chronic diarrhea; grinding poverty; war; stolen farm land; vaccination campaigns (in people whose immune systems are compromised, vaccines can easily wipe out their last shreds of health).

What about doctors and nurses in West Africa, who are treating Ebola patients? These health workers are falling ill with “the dreaded disease.”

Are they?

They’re working in very high temperatures, in clinic rooms likely sprayed with extremely toxic organophosphate pesticides. They’re sealed into hazmat suits, where temperatures rise even higher, causing the loss of up to five liters of body fluid during a one-hour shift. Then, recovering, they need IV rehydration, and they are doused with toxic disinfectant chemicals. They go back into the suits for another round of duty. One doctor reported that, inside his suit, there was (toxic) chlorine. These factors alone could cause dangerous illness and even death, and, of course, the basic symptoms of “Ebola.”

The experts were expressing grave doubts about Ebola, all the way back in 1977. Right at the beginning of the hysteria.

The 1977 reference here is: “Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever: Proceedings of an International Colloquium on Ebola Virus Infection and Other Haemorrhagic Fevers held in Antwerp, Belgium, 6-8 December, 1977.”

This report is 280 pages long. It’s well worth reading and studying, to see how the experts hem and haw, hedge their bets, and yet make damaging admissions:

For example, “It is impossible to consider the virological diagnosis of Ebola virus infection loose [apart] from the diagnosis of haemorrhagic fevers in general. The clinical picture of the disease indeed is too nonspecific to allow any hypothesis as to which virus may be responsible for any given case.”

Boom.

To those who point out there is a history of hemorrhagic (bleeding) fevers in parts of Africa, there is a history of horrendous malnutrition, one aspect of which is scurvy, which causes bleeding from all mucous membranes.

Bottom line: no need for a virus to explain the bleeding.

Then we have pesticides.

The reference here is “Measuring pesticide ecological and health risks in West African agriculture…” Feb. 17, 2014, published in Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society, by PC Jepson et al.

“The survey was conducted at 19 locations in five countries and obtained information from 1704 individuals who grew 22 different crops. Over the 2 years of surveying, farmers reported use of 31 pesticides…

“…certain compounds represented high risk in multiple environmental and human health compartments, including carbofuran, chlorpyrifos, dimethoate, endosulfan and methamidophos.

“Health effects included cholinesterase inhibition, developmental toxicity, impairment of thyroid function and depressed red blood cell count…”

The study also notes that “[p]esticide imports to West Africa grew at an estimated 19% a year in the 1990s…well ahead of the growth in agricultural production of 2.5%…” In other words, pesticides have flooded West Africa.

Here is another vital observation made in the study: “The distribution and sale of pesticides in West Africa is not effectively regulated. Multiple channels of supply commonly include the repackaging of obsolete or illegal stocks [extremely toxic] and the correspondence between the contents of containers to what is stated on the label is poor…”

Pesticide suppliers conceal banned pesticides—which they are taking a loss on, because they can’t sell them—and put them inside containers labeled with the names of legal pesticide

Let’s consider the pesticides specifically mentioned in the study.

Carborfuran—According to the New Jersey Dept. of Health and Senior Services’ Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet, exposure to Carbofuran “can cause weakness, sweating, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and blurred vision. Higher levels can cause muscle twitching, loss of coordination, and may cause breathing to stop [imminent death].”

Chloropyrifos, dimethoate, and methamidophos are organophosphates. The Pesticide Action Network describes organophosphates as “among the most acutely toxic of all pesticides…they deactivate an enzyme, Cholinesterase, which is essential for healthy nerve function.”

Endosulfan is being phased out globally, because it is extremely toxic and disrupts the endocrine system.

These pesticides can and do produce a number of the symptoms called “Ebola:”

Bleeding, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, stomach pain, coma.

But all this is swept aside in the hysteria about The Virus.

Here is a quote from a study, “Potential for bleeding with the new beta-lactam antibiotics,” Ann Intern Med December 1986; 105(6):924-31:

“Several new beta-lactam antibiotics impair normal hemostasis [body processes that stop bleeding]… These antibiotics often cause the template bleeding time to be markedly prolonged (greater than 20 minutes)… dangerous bleeding due to impaired platelet aggregation requires treatment with platelet concentrates.”

Here is a summary from MedlinePlus:

“The Clostridium difficile bacteria normally lives in the intestine. However, too much of these bacteria may grow when you take antibiotics. The bacteria give off a strong toxin that causes inflammation and bleeding in the lining of the colon…Any antibiotic can cause this condition. The drugs responsible for the problem most of the time are ampicillin, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and cephalosporins…”

So let’s look at the level of antibiotic use in West Africa and the Third World.

Voice of America, February 26, 2014, “…antibiotics have become the automatic choice for treating a child with a fever.”

AAPS (American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists): “For instance, in most areas of West Africa, antibiotics are commonly sold as over-the-counter medications.”

TWN (Third World Network): “…a survey carried out in 1999 showed that nearly one out of two antidiarrheal products in Third World countries contained an unnecessary antibiotic…” [and chronic diarrhea in the Third World is a leading cause of death, so you can be sure that these antidiarrheal drugs are consumed in great quantities].

“…75 products (including some antibiotics) which had been pulled out or banned in one or more European countries were identified in the Third World in 1991.”

Of course, banned antibiotics would be exceptionally toxic.

In West Africa, antibiotic use is sky-high…and antibiotics do cause bleeding.

Bleeding where? In the digestive tract.

In light of that, consider the following excerpt from the healthgrades.com article, “What is vomiting blood?”

“Vomiting blood indicates the presence of bleeding in the digestive tract…

“Vomiting blood may be caused by many different conditions, and the severity varies among individuals. The material vomited may be bright red or it may be dark colored like coffee grounds…”

Yes, it turns out that any source of internal bleeding in the digestive tract—such as overuse of antibiotics—can cause a person to vomit blood.

“The uniqueness” of “Ebola-blood-vomiting” is a fairy tale.

What else could cause the “Ebola” bleeding symptom in West Africa?

We have the fact that organophosphate insecticides are being widely used for indoor spraying, in West African homes and, surely, in clinics, to kill mosquitos. One study reports: “With high DDT resistance present throughout much of West Africa, carbamates and organophosphates are increasingly important alternatives to pyrethroids for indoor residual spraying (IRS).”

Among the effects, from severe exposure to organophosphates: diarrhea, tremors, staggering gait, blood disorders, death—all of which have been described in reference to Ebola.

And then there is this: “In nine patients suffering from organophosphate intoxication, platelet function and blood coagulation parameters were investigated…In five of nine patients a marked bleeding tendency was observed. The bleeding tendency in organophosphate intoxication is probably mainly caused by the defective platelet function.” (Klin Wochenschur, Sept. 3, 1984;62 (17):814-20, author: m. Zieman)

Bleeding. Not from a virus.

What about vaccines? A number of vaccination campaigns have been carried out in West Africa. I have found no in-depth independent investigations of the ingredients in these vaccines. But for example, a simple flu vaccine, Fluvirin, carries the risk of “hemorrhage.”.

Several other routine vaccines can cause vomiting. The HiB, for example.

We have this chilling report—From the (Liberian) Daily Observer, Oct. 14, “Breaking: Formaldehyde in Water Allegedly Causing Ebola-like symptoms”:

“A man in Schieffelin, a community located in Margibi County on the Robertsfield Highway, has been arrested for attempting to put formaldehyde into a well used by the community.”

“Reports say around 10 a.m., he approached the well with powder in a bottle. Mobbed by the community, he confessed that he had been paid to put formaldehyde into the well, and that he was not the only one. He reportedly told community dwellers, ‘We are many.’ There are agents in Harbel, Dolostown, Cotton Tree and other communities around the country, he said.”

“State radio, ELBC, reports that least 10 people in the Dolostown community have died after drinking water from poisoned wells.”

The ATSDR (US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) in its Guidelines for medical management of formaldehyde poisoning, lists these symptoms: “nausea, vomiting, pain, bleeding, CNS depression, coma…”

There are other sources of poisoning in West Africa. Their components and effects need further investigation.

For example: Firestone.

For nearly a century, the company has run a giant rubber plantation in Liberia. According to one estimate, Firestone controls 10% of the arable land in the country.

Aside from the wretched living and working conditions of the locals, who tap the trees for rubber, and bring their young children to work in order to meet Firestone daily quotas, there is the issue of massive pollution.

From irinnews: “LIBERIA: Community demands answers on rubber pollution”:

“MONROVIA, 4 June 2009 (IRIN) – People living next to Firestone Natural Rubber Company’s plantation in Harbel, 45km outside of Liberia’s capital Monrovia, say pollution from the concession is destroying their health, ruining their livelihoods and even killing residents.”

“Firestone’s Liberia rubber concession is the second largest rubber producer in Africa and employs some 14,000 Liberians.”

“Residents of the town of Kpanyarh, just next to Firestone’s rubber plantation in Harbel, say the creek from which they fish and drink their water in the dry season has been contaminated with toxins.”

“’We used to fish and drink the water,’ 67-year-old Kpanyarh resident John Powell told IRIN on a visit to the creek which runs just outside the town. He said the water became toxic in October 2008. ‘We can’t drink it any longer. Some of our people have already died from this. We have drawn Firestone’s attention to our plight but they have ignored it.’”

“In mid-May on an IRIN visit to the area, acidic fumes emanating from the creek caused people’s eyes to water and made it difficult to breathe.”

From BBC News: “The three-month investigation found that a plant south-east of the capital Monrovia was responsible for high [toxic] levels of orthophosphate in creeks.”

From laborrights.org: Because of lack of drinkable water on the plantation, “this situation leaves tappers and other unskilled employees and their families with no option but to drink from shallow wells and creeks.”

And of course, those creeks are heavily polluted.

Who knows how many and what toxic chemicals have been released from the Firestone plantation into the surrounding creeks and rivers?

A further investigation in West Africa could well turn up even more reasons for bleeding—none of which has anything to do with a virus. The region is rife with industrial operations which produce major pollutants—mining, offshore oil exploration and drilling, rubber-tapping, etc.

Then we come to the frightening press stories about the “Ebola-stricken, collapsing” doctors and health workers, who are treating patients in the Ebola clinics in West Africa.

These health workers have been wearing hazmat suits. Sealed off from the outside world, working shifts inside those boiling suits, where they are losing 5 quarts of body fluid an hour, they come out for rehydration, douse themselves with toxic chemicals to disinfect, and then go back in again.

One doctor told the Daily Mail he could smell intense fumes of chlorine while he was working in his suit. That means the toxic chemical was actually in there with him.

No wonder some health workers are collapsing and dying. No virus necessary.

From the Daily Mail, August 5, 2014, an article headlined, “In boiling hot suits…”:

“Doctor Hannah Spencer revealed how she wills herself to feel safe inside a boiling hot air-sealed Hazmat suit…”

“Boiling: Doctors and nurses lose up to five litres in sweat during an hour-long shift in the suits and have to spend two hours rehydrating after…”

“To minimise the risk of infection they have to wear thick rubber boots that come up to their knees, an impermeable body suit, gloves, a face mask, a hood and goggles to ensure no air at all can touch their skin.”

“Dr. Spencer, 27, and her colleagues lose up to five litres of sweat during a shift treating victims and have to spend two hours rehydrating afterwards.”

“At their camp they go through multiple decontaminations which includes spraying chlorine on their shoes.”

“Dr. Spencer: ‘We would like to keep a [patient] visit between 45 minutes and one hour, but now, we’re stretching it to almost two hours. We put ourselves through a very strong physiological stress when we’re using personal protection gear.’”

“‘We sweat, we’re losing water; we’re getting hotter and it wreaks havoc on the body. Our own endurance starts to wear down.’”

In another Daily Mail article (“What’s shocking is how Ebola patients look before they die…”), Dr. Oliver Johnson describes working in protective gear: “The heat of the suits is quickly overwhelming, as your goggles steam up and you feel the sweat dripping underneath. And the smell of chlorine is intense.”

Getting the picture? Imagine losing five quarts of water from your body in an hour. While you’re trapped inside a bulky hazmat suit. While you’re treating a patient who, for example, might want to escape the clinic because he’s afraid of you and your Western medicine.

Imagine needing two hours after you climb out of your suit to rehydrate. Then you go back for more. Of course you also decontaminate yourself with toxic chemicals, including chlorine.

But this has absolutely nothing to do with why you might fall ill. No. If you fall ill, or collapse, or suddenly die, it’s Ebola. The virus.

Sure it is.

No need to wonder. Don’t ask questions. Believe the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control. They always tell the truth.

—end of excerpts from my 2014 and 2017 Ebola articles—

Coda: Canadian investigator, Christine Massey, has been doing stunning work filing Freedom of Information Act requests for proof that various viruses have ever been isolated and purified (aka discovered). On March 15, 2021, she received a response from the CDC regarding the Ebola virus [2]. The CDC informed her they could find no records indicating the virus had ever been isolated and purified, from a patient sample.

Massey and her colleagues have filed seven other FOIA requests to various government agencies—seeking proof the Ebola virus has ever been isolated and purified—and the answer has always been the same: no such records exist.

Aside from exposing the horrendous truth about “Ebola” and what has really been happening in West Africa, I have another reason for writing this piece. I strongly recommend this method of investigation to independent researchers.

You start with the supposed medical cause of illness and death. You examine that cause and see whether it actually exists. At the same time, you carry out a parallel deep dive, in order to find out whether non-viral causes explain the symptoms of illness and death.

This is all aimed at “uncovering the cover story” that is being promoted to hide the crimes of corporations and governments.

In 1987, while I was writing my first book, AIDS INC., I probed a large amount of data and found my way into this approach. It worked then, and in succeeding years, it’s worked time and time again.

As I never tire saying: “the virus” is the greatest cover story ever invented.

SOURCES:

[1] https://www.yahoo.com/now/exclusive-white-house-preparing-order-for-enhanced-airport-screenings-for-ebola-203354978.html

I also recommend listening to David Crowe discuss an Ebola vaccine trial in 2017.

The Infectious Myth - Ebola, that’s enough! Yes! - 02.07.17 | The Infectious Myth (podbean.com)

Next let’s have a look at the magnificent The Final Pandemic by Drs Samantha and Mark Bailey and what is has to say about Ebola.

Fear-inducing “Viruses” Like Ebola…that Never Arrive

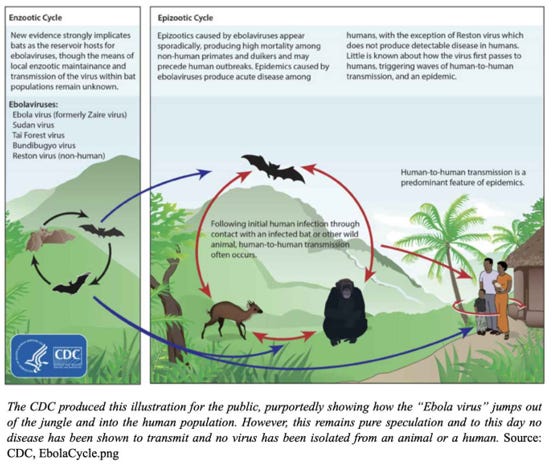

The mass media has a habit of making sure people are very aware of diseases that the average person has no chance of ever experiencing. One of the most-feared is so-called viral hemorrhagic fever, the most famous of which is Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease. It is alleged to be one of the most deadly and infectious viruses ever known. Like many other such “viral” diseases, Ebola was unknown to mankind until it supposedly jumped out of the jungle and started killing people in Africa in 1976. However, a look at the Ebola entry on Wikipedia makes interesting reading:

It is believed that between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or other body fluids of a person who has developed symptoms of the disease…Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat…Animals may become infected when they eat fruit partially eaten by bats carrying the virus. Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations…The natural reservoir for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate. EBOV [Ebola virus] is thought to infect humans through contact with mucous membranes or skin breaks. [authors’ emphasis]

There appears an awful lot of speculation rather than scientific evidence that a transmissible germ is at work. Furthermore, the clinical diagnosis of Ebola virus disease (EVD) raises more than a few problems given the non-specific nature of the symptoms:

Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of other diseases common in Africa, including malaria and dengue fever…The complete differential diagnosis is extensive and requires consideration of many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, shigellosis, rickettsial diseases, cholera, sepsis, borreliosis, EHEC [Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli], enteritis, leptospirosis, scrub typhus, plague, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, measles, and viral hepatitis among others. Non-infectious diseases that may result in symptoms similar to those of EVD include acute promyelocytic leukemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease, and warfarin poisoning.

So this introduces the problem of how Ebola is diagnosed and differentiated from all these other conditions. The CDC state that the three main methods are virus isolation, antibody tests, and the PCR. In this context it should be pointed out that the word ‘isolation’ does not mean what most people understand it to mean. Instead, the “isolation of ebola” describes a virological process where a crude human sample is taken and then:

(a) mixed with monkey kidney cells to see if the cells react,

(b) injected into the brains and abdomens of baby mice to see if it kills them, or

(c) injected into the abdomens of young guinea pigs to see if it kills them.

Most people would agree that the results of the above experiments would not mean that you had “isolated” anything, in fact, in each case you would have more things than you started with. Similarly, the antibody tests derived from these kind of experiments cannot be used to prove something that was never found in the first place. In any case, nothing has been established through scientifically controlled methods. (The experiments cited above mention “control cultures” only in the monkey kidney experiments but provided no details of their nature. Furthermore, there was no independent variable that could be identified as their samples contained crude mixtures, not “isolated viruses”.)

These days the main diagnostic tool for alleged ebola is the PCR (for detecting small genetic sequences) and more recently rapid antigen tests (for detecting proteins). The problem with both of these is the same as any “viral” diseases: if the claimed virus has never been isolated how were the genetic and protein tests matched to it? It is a product of the virologists circular reasoning where detecting these small genetic or protein fragments means there is a virus…because the virus is said to contain these bits. The stunning reality is that the physical isolation of any virus has never taken place to enable a determination of their very existence to be made.

However, whether the virologists want to claim they have “isolated” something or have produced tests that purport to detect this something, there remains a major problem with their hypothesis: why does Ebola not spread? The outbreaks are essentially limited to clusters in destitute African countries but the alleged highly infectious virus never appears in first world countries. There are cases like that of Craig Spencer, a New York doctor who became unwell a week after returning from Guinea where he was working with Doctors Without Borders in 2014. At that time, the New York Times documented his steps over a six day period:

He departed Guinea on a flight to Brussels…He departed Brussels and arrived in New York City. He was screened at Kennedy International Airport and reported no symptoms…he ate at the Meatball Shop…he walked on the High Line and stopped at Blue Bottle Coffee…he got off the High Line at 34th Street and rode the 1 Train to the 145th Street Station…he went on a three-mile run along Riverside Drive and Westside Highway…he went to the Community Supported Agriculture farm share at Corbin Hill Farm…he rode the A and the L trains to bowl with two friends at the Gutter in Williamsburg…He left the bowling alley at about 8:30 p.m., returning to Manhattan in an Uber taxi…He first reported a low-grade fever of 100.3 at 10:15 a.m. Medical workers, wearing full protective gear, picked him up from his home in Harlem…Shortly after 1 p.m., he arrived at Bellevue Hospital Center.

Despite Spencer’s travels about the city over several days, not one other person in New York came down with Ebola. The explanation offered for this is that, “people infected with Ebola cannot spread the disease until they begin to display symptoms, and it cannot be spread through the air. As people become sicker, the viral load in the body builds, and they become increasingly contagious.” This convenient story apparently involved remarkably specific knowledge of the disease given all the aforementioned speculations regarding Ebola.

Wikipedia has a “List of Ebola outbreaks” page where all of the recorded incidents of Ebola are in poor African countries apart from a tiny minority. Of these, as of September 2022, there were only two deaths amongst people who were based outside of Africa at the time they were said to be “infected,” and both were in Russia. The first was in 1996 in the Sergiev Posad laboratory as described by the Washington Post in a 2014 article:

She was an ordinary lab technician with an uncommonly dangerous assignment: drawing blood from Ebola-infected animals in a secret military laboratory. When she cut herself at work one day, she decided to keep quiet, fearing she’d be in trouble. Then the illness struck. “By the time she turned to a doctor for help, it was too late,” one of her overseers, a former bioweapons scientist, said of the accident years afterward. The woman died quickly and was buried, according to one account, in a “sack filled with calcium hypochlorite,” or powdered bleach.

The second death was also said to have occurred in a laboratory accident in 2004 as reported at the time in Science:

A Russian scientist working on an Ebola vaccine died last week following a lab accident. On 5 May, Antonina Presnyakova, 46, pricked her hand with a syringe after drawing blood from infected guinea pigs in an ultrasecure biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) facility at the Vektor Research Institute of Molecular Biology, a former bioweapons lab near Novosibirsk, Russia. She was hospitalized immediately, says a lab official, developed symptoms 1 week later, and died on 19 May.

Apart from these second-hand reports, there is no other evidence that has been made available for us to analyze exactly what happened to these two women. Neither of the stories provided any adequate scientific information and essentially remained at the level of hearsay.

More details were made available in the (nonfatal) case of Geoffrey Platt, a British laboratory technician said to have, “contracted Ebola in an accidental needlestick injury,” at the Porton Down campus in 1976. The authors have previously refuted the claims that he was infected with anything and exposed the uncontrolled experiments that were presented as evidence for a “virus” at work.

The most straightforward conclusion for the reason why the “highly infectious” Ebola disease has never spread around the world is because there is nothing to spread. Based on current statistics, an individual in a developed country is more likely to be struck by lightning twice than killed by Ebola disease, whatever that may be. There are plenty of reasons why people get sick in destitute areas from the multiple environmental toxicities and stressors they are exposed to. Unfortunately, the toxicologists and nutritionists are not given a seat at the table when the “virus hunters” have taken center stage and convinced others into thinking that their pet deadly germ is the only cause of such diseases.

And lastly let’s look at the magnificent deep dive that Mike Stone did into the Zaire 1976 Ebola “outbreak” in these two articles. This is ground zero for the Ebola story.

I will provide a summary and a Q&A of both of these excellent articles.

The Ebola “Virus” Part 1 – ViroLIEgy

The Ebola “Virus” Part 2 – ViroLIEgy

Summary

The 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire, traditionally attributed to a new “virus”, may have been mischaracterized. The articles argue that the evidence for a novel “virus” was weak and inconsistent. Instead, Mike Stone suggests that the likely cause of the “outbreak” was the side effects of toxic medications, particularly chloroquine, administered through unsafe injection practices at Yambuku Mission Hospital.

Key points supporting this alternative explanation include:

The symptoms of Ebola closely match known side effects of chloroquine and other drugs used.

The outbreak centered around the hospital and spread primarily through injections.

The outbreak ended when the hospital closed and injections stopped.

No “virus” was ever properly isolated or purified from patients.

Antibody tests used to identify the “virus” were unreliable and inconsistent.

The alleged Ebola “virus” was indistinguishable from the previously described Marburg “virus”.

The articles explain that the Ebola outbreak was a case of iatrogenic illness (caused by medical treatment) rather than a new viral disease.

According to Mike Stone's research, the main untruths or misrepresentations in the official Ebola story include:

“virus” isolation: No Ebola “virus” was ever properly purified or isolated directly from patient samples. The claimed "isolation" involved unpurified cell cultures with many contaminants.

“virus” uniqueness: The particles observed were indistinguishable from Marburg “virus”, yet were claimed to be a new “virus” based solely on questionable antibody test results.

Antibody testing reliability: The antibody tests used to identify Ebola were inconsistent and unreliable, with many false positives and negatives.

Transmission theory: The idea that Ebola spreads through person-to-person contact was not established. The primary mode of spread appeared to be through hospital injections.

Natural origin: There was no evidence for the “virus's” natural reservoir or how it first infected humans.

Symptom specificity: Ebola symptoms were not unique and could be easily confused with other diseases or even pregnancy.

Mortality cause: Deaths attributed to Ebola were likely caused by the side effects of toxic medications and unsafe injection practices.

Asymptomatic cases: The existence of asymptomatic Ebola infections contradicts the “virus” theory and suggests problems with diagnostic criteria.

Outbreak control: The outbreak ended when injections stopped, not due to “virus” containment measures.

Scientific consensus: Stone explains that there was no true scientific consensus on Ebola's cause, with major discrepancies between research teams glossed over in the final reports.

These points challenge the fundamental narrative of Ebola as a naturally occurring, highly infectious viral disease.

If Ebola is so deadly, how can it also be asymptomatic?

This highlights a significant inconsistency in the official Ebola narrative. According to Mike Stone's analysis, this contradiction undermines the credibility of the Ebola virus theory.

The official story presents Ebola as an extremely deadly disease with a mortality rate as high as 88% in the 1976 outbreak. However, the same reports also claim the existence of asymptomatic cases, where individuals tested positive for Ebola antibodies but never showed any symptoms.

This inconsistency is problematic for several reasons:

It contradicts the idea of Ebola as a universally severe and often fatal disease.

It raises questions about the reliability of the antibody tests used to identify Ebola cases.

It challenges the understanding of how the “virus” supposedly interacts with the human immune system.

Stone argues that this contradiction is evidence of flawed methodology and inconsistent theorizing in Ebola research. He suggests that the presence of antibodies in healthy individuals might instead indicate that these tests are not specific to Ebola, or that they're detecting common, harmless substances rather than evidence of a deadly virus.

This discrepancy between deadly symptoms and asymptomatic cases is one of many points that Stone uses to question the entire foundation of Ebola as a distinct viral disease.

35 Questions & Answers

Question 1: What is Ebola “virus” and when was the first major outbreak recorded?

Ebola “virus” is said to be a pathogen causing hemorrhagic fever. The first major outbreak was recorded in 1976 in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo). Between September 1st and October 24th, 1976, 318 cases of acute hemorrhagic fever occurred in northern Zaire, resulting in 280 deaths and only 38 serologically confirmed survivors.

Question 2: Who was Dr. Peter Piot and what was his role in the discovery of Ebola?

Dr. Peter Piot was a medical school graduate training to be a clinical microbiologist in 1976. He received blood samples from a sick nurse in Zaire and is credited as one of the researchers who ultimately discovered the new "“virus”." However, there was controversy surrounding this claim as many others were involved in the discovery process.

Question 3: How is Ebola “virus” related to Marburg “virus”?

Ebola “virus” is described as morphologically similar to Marburg “virus” but immunologically distinct. Both “viruses” cause similar hemorrhagic fever symptoms. The particles claimed to be Ebola “virus” were admitted to be identical to those associated with Marburg “virus”, yet they were declared different based on non-specific indirect antibody results.

Question 4: What are the main symptoms of Ebola “virus” disease?

The main symptoms of Ebola “virus” disease include fever, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. These symptoms are non-specific and can be confused with other diseases common to the area.

Question 5: How is Ebola “virus” thought to be transmitted?

Ebola “virus” is thought to be transmitted through direct contact with the blood, body fluids, and tissues of infected animals or people. It's believed to first spread from animals to humans, then human-to-human through contact with bodily fluids of infected individuals. However, transmission is said to occur only when the infected person is symptomatic.

Question 6: What role did Yambuku Mission Hospital play in the 1976 Ebola outbreak?

Yambuku Mission Hospital (YMH) was identified as a major source of dissemination for the Ebola outbreak. The index case received an injection of chloroquine at the hospital's outpatient clinic. Subsequently, several other persons who had received injections at YMH also developed symptoms. The hospital used only five syringes and needles for all patients throughout the day, which were rinsed in warm water between uses but not properly sterilized.

Question 7: How were chloroquine and other medications used in treating patients during the outbreak?

Chloroquine was initially used to treat the index patient for presumptive malaria. Other medications used included aspirin, antibiotics, corticosteroids, hydrocortisone, immunoglobulin, and experimental drugs like moroxydine. These were often administered through parenteral injections. Notably, chloroquine is known to have side effects that closely mimic Ebola symptoms, including gastrointestinal bleeding.

Question 8: What is the significance of parenteral injections in the spread of the disease?

Parenteral injections were identified as the principal mode of administration for nearly all medicines at YMH. This practice was strongly associated with the spread of the disease. The single common risk factor for 85 of 288 cases was the receipt of one or more injections at YMH. Importantly, no person whose contact was exclusively through parenteral injection survived the disease.

Question 9: How did the World Health Organization (WHO) conduct its epidemiological investigation?

The WHO coordinated with three teams of researchers from Antwerp, Porton Down, and the CDC to investigate the outbreak. They deployed surveillance teams to find past and active cases, detect possible convalescent cases, educate the public, and establish the termination of the outbreak. The teams conducted house-to-house examinations in affected villages and collected blood samples for testing.

Question 10: What were the case definitions for Ebola (probable, possible, proven) during the outbreak?

A probable case was defined as a person in the epidemic area who died after one or more days with specific symptoms and had received an injection or had contact with a probable/proven case. A proven case was someone from whom Ebola “virus” was isolated or who had specific antibody titers. A possible case was a person with headache and/or fever who had contact with a probable/proven case within three weeks.

Question 11: What were the objectives of the surveillance teams during the outbreak?

The surveillance teams aimed to find past and active cases of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, detect possible convalescent cases, educate the public about the nature and prevention of the disease, and establish the termination of the outbreak. They were trained in differential diagnosis, epidemiology, personnel protection, and data collection methods. Each team was equipped with vehicles, protective gear, and medications.

Question 12: What challenges were faced in the differential diagnosis of Ebola?

Differential diagnosis of Ebola was challenging due to its non-specific symptoms that mimicked other common diseases in the area, including influenza, malaria, typhoid fever, meningitis, and even pregnancy. The WHO and CDC both stated that diagnosis based on symptoms alone was difficult and required indirect laboratory methods to confirm infection. This made it nearly impossible for the surveillance teams to accurately diagnose Ebola cases based solely on clinical presentation.

Question 13: What techniques were used to isolate and identify Ebola “virus”?

The main techniques used were cell culture, electron microscopy, and indirect antibody testing. Blood samples from suspected cases were inoculated into Vero cell cultures. The resulting cell cultures were then examined under electron microscopy for “virus”-like particles. Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) tests were used to detect antibodies in patient sera. However, no purification or isolation of “virus” particles directly from patient samples was performed.

Question 14: How were Vero cells used in “virus” isolation attempts?

Vero cells, derived from African green monkey kidneys, were used as the primary cell culture system for attempted “virus” isolation. Blood samples from suspected Ebola cases were inoculated into Vero cell cultures. These cultures were then observed for cytopathic effects (cell death) and examined under electron microscopy for “virus”-like particles. However, the cell culture process involved adding many foreign materials and contaminants, which is the opposite of purification and isolation.

Question 15: What was the role of electron microscopy in identifying the Ebola “virus”?

Electron microscopy was used to visualize particles in cell cultures and liver samples that were claimed to be Ebola “virus”. These particles were described as filamentous structures, approximately 100 nm in diameter and varying in length from 300 nm to more than 1500 nm. However, the particles observed were not purified or isolated directly from patient samples, and they were morphologically indistinguishable from those associated with Marburg “virus”.

Question 16: What is Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) testing and how was it used in the outbreak?

Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) testing is a method used to detect antibodies in patient sera. In the Ebola outbreak, it was used to identify "proven" cases and to differentiate Ebola from Marburg “virus”. However, the results were inconsistent and unreliable. Some individuals with no symptoms or contact with Ebola patients tested positive, while others with symptoms and direct contact tested negative. The WHO admitted that the specificity of these reactions was doubtful and that a better method for measuring Ebola “virus” antibodies was needed.

Question 17: What were the findings of the virological studies conducted during the outbreak?

Virological studies were limited. Ebola “virus” was reportedly isolated from blood specimens in 8 of 10 attempted cases using Vero cell cultures. Particles claimed to be Ebola “virus” were found in 3 of 4 postmortem liver biopsies. However, these particles were morphologically indistinguishable from Marburg “virus”. The studies lacked proper controls and purification procedures, and the cell culturing process involved adding many foreign materials, which is the opposite of isolation.

Question 18: What was the mortality rate associated with Ebola in the 1976 outbreak?

The mortality rate for the 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire was reported to be extremely high at 88%, with 280 deaths out of 318 cases. This was described as the highest mortality rate on record for any disease except rabies. However, it's important to note that the mortality rate was higher among those who received parenteral injections at the hospital compared to those who didn't.

Question 19: What evidence was found for asymptomatic Ebola infections?

Evidence for asymptomatic Ebola infections came from serological studies. Antibodies were found in some individuals who had no history of illness or contact with known cases. For example, sera from 5 persons aged 8-48 years in neighboring villages with no reported cases contained IFA antibodies. This finding was used to suggest the possibility of subclinical infections or that the “virus” might be endemic to the region.

Question 20: How did researchers differentiate between Ebola and Marburg “virus”es?

Researchers claimed to differentiate Ebola from Marburg “virus” primarily based on indirect antibody test results, despite the “viruses” being morphologically indistinguishable. The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) test showed different reactions for Ebola and Marburg antibodies. However, these results were inconsistent and their specificity was doubted. The differentiation was maintained despite all other evidence pointing to the particles being identical to those associated with Marburg “virus”.

Question 21: What was the Center for Disease Control's (CDC) involvement in Ebola research?

The CDC in Atlanta was one of three teams involved in the Ebola investigation. They received samples from Porton Down and were tasked with determining whether the “virus” was new or identical to Marburg. The CDC team claimed to show that the Yambuku outbreak was caused by a previously unknown “virus”, not Marburg. They were given credit for the final determination of Ebola as a new “virus”, despite the inconsistencies in their findings with those of the other research teams.

Question 22: How did Porton Down laboratory contribute to the Ebola investigation?

Porton Down, a British military laboratory, was one of the three main research centers involved in the Ebola investigation. They received samples from Antwerp for confirmation and further study. Porton Down conducted cell culture experiments, animal inoculation studies, and electron microscopy examinations. Their findings, like those from Antwerp, showed particles identical to Marburg “virus”. However, they deferred to the CDC's conclusion that it was a new “virus”.

Question 23: What is hypovolaemic shock, and how was it associated with Ebola patients?

Hypovolaemic shock is a condition where severe blood loss leads to the heart being unable to pump enough blood throughout the body, resulting in multiple organ failure. In the Ebola outbreak, it was observed in patients at Ngaliema Hospital. All three patients studied there were said to have died from hypovolaemic shock. One possible cause of this condition is damage to the stomach, which could potentially be linked to the multiple injections of toxic medications these patients received.

Question 24: How are Ebola symptoms similar to pregnancy symptoms?

According to the WHO, many symptoms of Ebola disease are quite similar to pregnancy symptoms. This similarity created difficulties in diagnosing Ebola, especially among women of childbearing age. Interestingly, women aged 15-29 years had the highest incidence of the disease, which was strongly related to attendance at prenatal clinics where they received injections. This overlap in symptoms raises questions about the accuracy of Ebola diagnoses, particularly in pregnant women.

Question 25: What is disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and how is it related to Ebola?

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a blood clotting condition that can lead to massive bleeding. It's associated with inflammation, infection, and cancer. In the context of the Ebola outbreak, DIC was mentioned as a possible complication of the disease. Some patients were treated with heparin in anticipation of DIC. However, the evidence for DIC in Ebola patients was described as fragmentary, and it may have been one of several factors contributing to the bleeding and shock observed in severe cases.

Question 26: What were the key points in the WHO's 1978 report on the Zaire Ebola outbreak?

The WHO's 1978 report detailed the outbreak's timeline, epidemiology, and clinical features. Key points included: the outbreak's origin at Yambuku Mission Hospital, the role of parenteral injections in disease spread, the high mortality rate, and the eventual control through stopping injections and isolating patients. The report also highlighted the challenges in diagnosis, the limitations of virological studies, and the need for better antibody testing methods. Importantly, it admitted that the means by which the “virus” was introduced into the hospital would probably never be precisely known.

Question 27: How did the outbreak in Zaire compare to the simultaneous outbreak in Sudan?

The outbreaks in Zaire and Sudan occurred simultaneously but showed some differences. The illness in Zaire had fewer respiratory symptoms, a shorter clinical course, and a higher fatality rate compared to Sudan. However, the agents recovered from both countries were thought to be identical, although definitive tests had not been conducted at the time of the report. The link between the two outbreaks could not be definitively established, although it was speculated that an infected person might have traveled from Sudan to Yambuku.

Question 28: What was the importance of stopping injections in controlling the outbreak?

Stopping injections at Yambuku Mission Hospital was described as the single most important event in terminating the outbreak. The epidemic waned when the hospital was closed due to a lack of medical staff, effectively ending the practice of giving injections. This observation strongly suggests that the injections themselves, rather than a “virus”, may have been the primary factor in spreading the disease. The WHO noted that “virus” transmission was interrupted by stopping injections and isolating patients in their villages.

Question 29: How did the WHO report explain the higher incidence of the disease in women aged 15-29?

The WHO report noted that women aged 15-29 had the highest incidence of disease, a phenomenon strongly related to attendance at prenatal and outpatient clinics at the hospital where they received injections. This group comprised 22 of 24 injection-associated cases in a 21-village study. The report did not explore alternative explanations for this pattern, such as the possibility that pregnancy symptoms were being misdiagnosed as Ebola, or that pregnant women might be more susceptible to adverse effects from the injections.

Question 30: What were the main criticisms of using antibody tests to identify Ebola cases?

The main criticisms of antibody tests included their lack of specificity and inconsistent results. The WHO admitted that the Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) data were doubtful when samples from unrelated populations also showed "antibodies" to Ebola. Many individuals with no symptoms or contact with Ebola patients tested positive, while others with symptoms and direct contact tested negative. The WHO stated that a better method for measuring Ebola “virus” antibodies was needed to interpret the serological findings accurately.

Question 31: How did the researchers attempt to determine the origin of the Ebola “virus”?

Researchers speculated that the Ebola “virus” might have been brought to Yambuku from Sudan, though they couldn't establish a definitive link. They noted that people could travel between Nzara (Sudan) and Bumba (Zaire) in four days, suggesting an infected person might have introduced the “virus” to Yambuku hospital. However, intensive searches failed to detect definite evidence of this link. The researchers admitted that the source of Ebola “virus”, like Marburg “virus”, remained completely unknown beyond being of African origin.

Question 32: What were the main differences observed between cases acquired by injection versus those by contact?

Cases acquired by injection were observed to be different from those due to contact with another case. The mortality rate was higher among those who received injections, and no person whose contact was exclusively through parenteral injection survived the disease. In one study, secondary transmission rates were also higher from index cases that were parenterally induced. The researchers speculated that increased “virus” replication following parenteral infection might account for these differences, but other causes were not excluded.

Question 33: How did the WHO report address the possibility of Ebola being endemic to the region?

The WHO report raised the possibility that Ebola “virus” might be endemic to the Yambuku area. This speculation was based on finding antibodies in a few individuals who had no known contact with Ebola “virus” during the epidemic. The report suggested that the agent might occasionally be transmitted to humans from an unknown reservoir. However, it also acknowledged that a definitive answer was essential for further ecological exploration of what was described as a "very mysterious agent."

Question 34: What historical practices were used in rabies vaccination, and how do they relate to the Ebola outbreak discussion?

Historically, rabies vaccination involved a series of painful injections into the stomach. Until the 1980s, treatment could include up to 21 injections into a person's abdomen using a long needle. This practice is mentioned in relation to the Ebola outbreak because both rabies and Ebola were associated with high mortality rates and dangerous injection practices. The discussion raises the possibility that some of the Ebola patients might have received intraperitoneal injections (into the stomach cavity) of toxic drugs, potentially explaining the increase in gastrointestinal bleeding observed.

Question 35: What alternative explanations were proposed for the outbreak, and how do they critique virology methods and “virus” theory?

Alternative explanations proposed that the outbreak was primarily caused by the toxic effects of parenteral injections rather than a new “virus”. Critics argue that the symptoms associated with Ebola could be explained by the side effects of drugs like chloroquine, which is known to cause gastrointestinal problems and unusual bleeding. They point out that the outbreak ended when injections stopped, suggesting a direct link between the medical interventions and the disease. This critique challenges the “virus” theory by highlighting the lack of proper isolation and purification of the supposed Ebola “virus”, the inconsistencies in antibody testing, and the reliance on indirect evidence to support the existence of a new pathogen.

I appreciate you being here.

If you've found the content interesting, useful and maybe even helpful, please consider supporting it through a small paid subscription. While everything here is free, your paid subscription is important as it helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. It also helps keep it free for those that cannot afford to pay.

Please make full use of the Free Libraries.

Unbekoming Interview Library: Great interviews across a spectrum of important topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Concise summaries of important books.

Stories

I'm always in search of good stories, people with valuable expertise and helpful books. Please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com

For COVID vaccine injury

Consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Baseline Human Health

Watch and share this profound 21-minute video to understand and appreciate what health looks like without vaccination.

Thank you for this excellent rundown on "Ebola" . . . when people are confronted with the "missing virus" facts, one of the many comebacks is: What about Ebola? I remembered reading Jon Rappaport's article and the other truth about the virus myths. A handy cover-up for environmental poisons. The virus lie has tentacles throughout our culture. Onward with your excellent work!

Thank you all for this wonderful work

I have 2 dead sisters a dead son and a dead friend in USA a daughter with SLE and I have spondylosis all from bio weapons

God have mercy on all the victims in African nations

God will Judge these criminals