This essay by Zinnia is just so bloody good. It is magnificent.

It was published in January, and now in May it remains the front runner for me for the essay of 2024. It will be hard to beat.

It’s worthy of amplification.

It is an important read for everyone, but especially if you are raising a young woman, today.

It connects with many other themes I am interested in and covered by this substack.

It is the only essay on Zinnia’s substack, and hopefully there will be more.

She is worth following.

e-girl esoterica | zinnia | Substack

Enjoy

A Partial Explanation of Zoomer Girl Derangement (substack.com)

i.

How strange. It stained her skirt: Red shame.

How utterly unremarkable. No stark transformation.

But her mother, she spoke in a whisper.

Told her not to tell her father

Her skirt, smuggled into the laundry.

Illicit. Like the thing she’d become

A woman, she murmured to her dolls.

How strange, she thought:

She had whispered.

As if she’d committed a crime

ii.

Nubile legs peeked through her schoolgirl skirt.

Rose bud breasts and narrow hips:

Alluring.

Eyes trapped by

untouched flesh, kissed by the glow of youth,

Lilting laughter left her girlish pout.

Innocence: What a thrill.

A flash of skin: Ecstasy

iii.

How strange. It stained her skin: Strange gaze

Eyes poked at her bony limbs

Rippled her skin till her hair stood up

Illicit.

As if she’d committed a crime

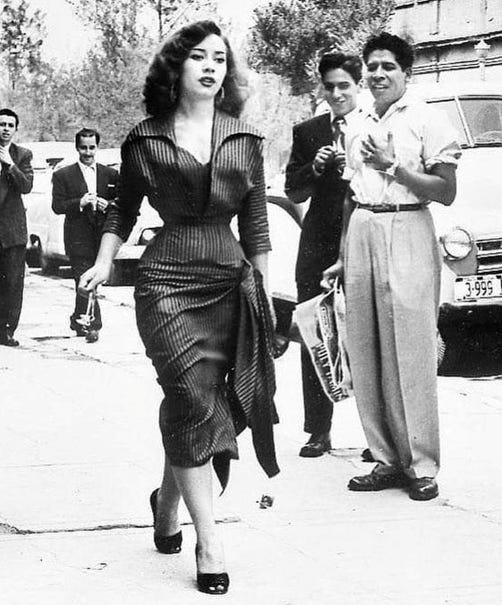

Girlhood ends when the world looks at you. One day, you wake up and you’re a sex object. This is terrifying. Men want you and they are bigger than you and stronger than you. They do not see you; they just like what they see. Hungry eyes; how do you keep rabid animals at bay? But if you are of a certain disposition, you may feel a certain kind of thrill, walking into a room and having all eyes on you. Men may be bigger and stronger, but you are smarter. If you bat your eyes at the man from across the bar, he’ll buy you a drink; if you cry when the police officer pulls you over, he’ll let you off easy.

Girlhood ends when the world looks at you. One day, you wake up and you’re a sex object. This is terrifying. Men want you and they are bigger than you and stronger than you.

As you come of age, you must confront a paradox: your greatest source of power, your desirability, is your greatest source of vulnerability. Girls react to this paradox in various ways; some girls retreat into themselves, despising the male gaze, others embrace it, perhaps out of insecurity, perhaps out of ambition. Whatever the case may be, as you come of age, you come to terms with it. You accept your desirability; but you do not let it define you; you pursue other things, hobbies, interests, passions. You do not resent the male gaze, but you do not hunger for it either; this is the healthiest way to come to terms with your newfound status as “sex-object.”

But the path to this enlightened state is fraught with pitfalls; young women often fall into self-destructive cycles: either hungering for sexual attention, or rejecting it entirely (which necessarily implies a rejection of the female body). In the digital age, these pitfalls are far more enticing to young girls. They can seem like a way out, a means to salvation or a means to power: a young girl can find endless amounts of attention online to inflate her ego, or she can find sanctuary from male attention in niche online spaces: trans Tumblr, pro-anorexia Twitter, and the like. Both paths lead to destruction. Today, young women face more and more traps while navigating their place in the world as women, contributing to rising rates of female mental illness and unhappiness.

“Norma Jean Mortensen, the future Marilyn Monroe, spent part of her childhood in Los Angeles orphanages. Her days were filled with chores and no play. At school, she kept to herself, smiled rarely, and dreamed a lot. One day when she was thirteen, as she was dressing for school, she noticed that the white blouse the orphanage provided for her was torn, so she had to borrow a sweater from a younger girl in the house. The sweater was several sizes too small. That day, suddenly, boys seemed to gather around her wherever she went (she was extremely well-developed for her age). She wrote in her diary: They stared at my sweater as if it were a gold mine.”

— Robert Greene, Art of Seduction

There’s a certain kind of girl who grows up a little too fast: her shirts are a little too low cut, her manner of speaking a little too flirtatious. This kind of girl instinctively understands the power her sexuality can command; she knows little of how it can invite danger.

But her mother knows, and she will have her change her top before she leaves for school. This kind of “policing” of young women’s bodies violates progressive sensibilities. “Minors shouldn’t be sexualized!” they say, as if such legal technicalities prevent men from looking at a pretty pair of breasts. What progressives miss is that these kinds of boundaries set by parents, schools, and the larger community serve an important protective function, they safeguard young girls from acting in a manner they may later regret.

However, within the current sex-positive framework, such constraints are seen as old-fashioned and oppressive. Now, if a young woman wants to, she can dress as if she’s 21 at the age of 15, and post pictures of herself on public social media for all to see. In fact, she is incentivized to, both by the sex-positive paradigm, and by the fact that social media clout confers status.

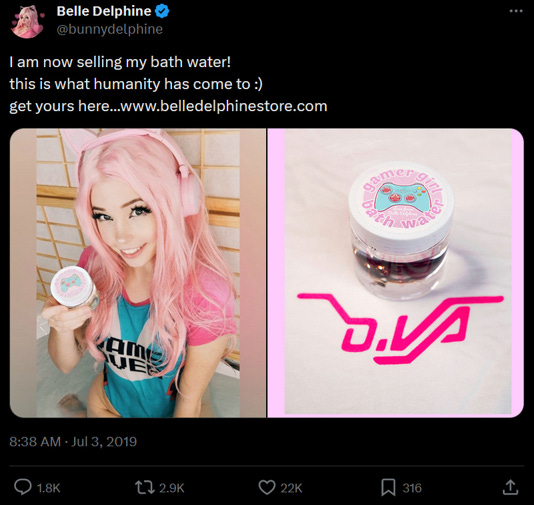

Moreover, even if one tried to police this kind of behaviour, it is a bit too tricky. Teenagers often set up alternate accounts parents don’t have access to, and frequently lie about their age online. This is to be expected, and so you get women like Belle Delphine:

For those of you that are not in the know, Belle Delphine is a controversial Internet figure, most well-known for selling her bathwater online. Delphine grew up on the Internet, and cultivated much of her following while she was underaged. She was a pioneer: the first notable female internet personality to integrate gaming and anime aesthetics into her public persona (an open niche at the time, the gamer-girls of the 2010s were no match for her allure); this, combined with her raunchy and over the top persona, earned her millions of followers. At the height of her fame, she decided to sell her bathwater. It sold out in a matter of three days. Delphine in many ways was an ordinary girl, but through her clever usage of social media, she was able to turn herself into a star.

They’ve never seen me

Only limb, hip, breast

Nor have they ever heard me

Simply gasp, coo, moan

Desire, what a scam,

I sell it.

Moonlit nights punctuated by Splenda kiss,

groping silicone skin.

While my pop song laugh lulls

them into illusion - like a magician

I distract: with skin so solid they look right through me - like a bubble.

I refract: bend the light like desert air.

How pretty, how alluring, they can’t help but

grasp me,

lick me,

scratch me,

bite me,

fuck me.

Though,

they could never hold me.

One touch and I dissolve

Delphine pioneered a new feminine archetype: the OnlyFans girl. She did it before it was popular. OnlyFans is a platform downstream of the “private snapchats” used by the e-whores of old. OnlyFans is the logical endpoint of Instagram. Once online platforms allowed women to leverage their sexual power in a soft sense, it was only a matter of time before women started leveraging their sexual power in a hard sense: engaging in various forms of online prostitution. It is common to see normal looking girls with OnlyFans links in their Instagram bios. One particularly pernicious effect of this is how men will now comment on a regular woman’s Instragram with a request for an OnlyFans link, making the assumption of sexual availability in a way they didn't before. Normalization of the OnlyFans phenomenon means that every woman could have one; therefore suspicion falls on all women.

In economics, this is referred to as a "market for lemons". When counterfeit or substandard products are indistinguishable from authentic, premium quality, the eventual result is that even the best products are treated as inferior.

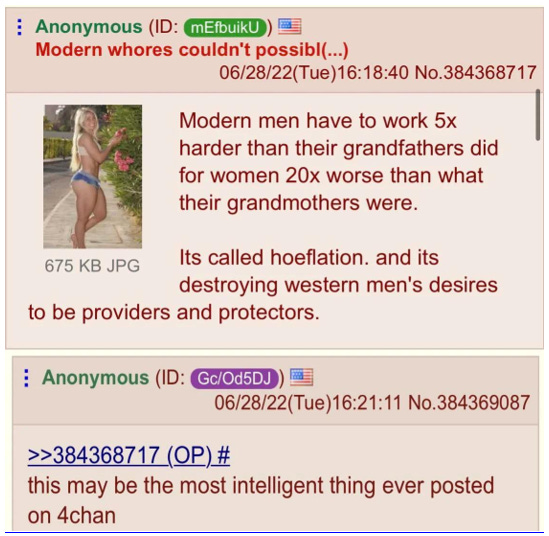

Women are experts at concealing, disguising, or downplaying their flaws. Men become accustomed to being tricked, misled, or exploited. Bitterness and resentment germinates among young bachelors, as this trend intensifies and expands over time. Men expect an information asymmetry, which is that women can deceive them, which creates a posture of preemptive distrust.

Gresham's law postulates "bad money drives out good money." We can apply this economic logic to the sexual marketplace, which is that in an era of suspicion, paranoia, distrust, betrayal, promiscuity, and de facto casual prostitution, young men begin to resent women as a group — even beautiful young virgins are treated as sluts, and whores.

War between the sexes erupts.

A Cold War, defined by surveillance, hatred, and proxy conflicts.

Distrust is a natural part of romance. Women and men have always been motivated to present the best, most flattering version of themselves, and to embellish with white lies... innocuous ornamentation to maximize their romantic options. Thus some level of discontent, and deceit between genders, seems unremarkable. But a difference in quantity is a difference in kind. The modern sexual landscape is an extreme, hideous departure from past normative behaviour.

Social media is a "gateway drug" to hardcore pornography, and a life as a digital prostitute.

Hoeflation is real. Young women today are not the same as their mothers.

Delphine is not the only young woman who was able to leverage her sexuality into making millions. Many women have turned into stars in this way, intentionally or unintentionally (Gio Scotti comes to mind). Pretty women can simply have fame, power, and fortune handed to them, simply for existing. Being beautiful makes you powerful.

Hoeflation is real. Young women today are not the same as their mothers.

But being beautiful can be terrifying. The male gaze becomes an inescapable fact of life. Your existence becomes that of a gazelle’s, a prey animal, every action you take is informed by a calculus weighing the risk of rape against potential wins. The kindness of men becomes suspect; the pressure to be desirable, over-powering. The male gaze becomes suffocating and you look for an escape.

And the solution is simple. Make yourself undesirable. But that comes with a cost. Beauty matters, and if you make yourself undesirable directly, you sink to the bottom of the normie-social hierarchy. What you need is to find an alternative hierarchy, one that rewards you for fashioning yourself in a way contrary to male desires. A prime example: Eating Disorder Twitter.

Pro-anorexia spaces are entirely defiant of normative male sexual preferences. Starving yourself to appeal to purely feminine aesthetic preferences – cuteness, daintiness, girliness – at the cost of your fuckability; starving yourself to desex yourself, to free yourself of the male gaze, is a liberatory act. It is certainly far more feminist than fattening yourself and then demanding that men find you appealing, as the body-positive activists often do. Anorexia is a complex mental illness, and women develop it for a variety of reasons, but part of its allure stems from its ability to provide young women an aesthetic alternative, a way of being beautiful but entirely invisible to men ... though this strategy has its limitations. Male sexuality is fascinating in its ability to fetishize everything about women, even fetishizing grotesque manifestations of women’s desire to escape male sexuality.

Of course, if you don’t have the will to starve yourself till your tits disappear, well then, you can always chop them off:

“My gender identity came into focus soon after having top surgery. Top surgery gave me the embodied feeling of having a flat chest. Top surgery allowed me to feel at home in my skin, to feel at ease in my clothes. Top surgery freed me from the feminized experience and sexualized meaning of having breasts. Now, my body feels like it belongs to me and is made up of the parts I want. That's why I now also use they/them pronouns and I describe myself as genderqueer.” — Kael Reid, CBC First Person

Gender dysphoria is a pathological response to the threat of male sexual attention. And as we continue to live in an image-dominated hyper-realistic culture where beauty is emphasized and rewarded to a disproportionate degree, this pathological response will only become more common:

“I just want my chest to be free, broad and bare with the sun on my back and my eyes towards the sky.

And every hot day I imagine being able to shed my shirt and dive into cool water.

But I can’t because when people outside look, they see vulgarity and sex no matter my intentions. They see an object for someone to hold and touch. They see a chest that is not mine, but for their viewing pleasure.

So I put on my shirt and count the days until maybe I’ll be free from this”

— anon, Tumblr

Gender dysphoria is a pathological response to the threat of male sexual attention.

A disproportionate fear of male sexuality (and its resulting consequences) is not the only kind of pathological response young women have to today’s image dominated digital landscape. Another common response: self-hatred. Young women are bombarded with images of extremely beautiful women every single day; women who are once in a lifetime beauties; women who are products of intense diets, cosmetic surgery, photographic trickery, photoshop, and filters. Women who are not even real. But the human mind does not grasp this hyper-real element. For the lizard brain, looking at a digital image of an inhumanly beautiful woman is no different from looking at an inhumanly beautiful woman incarnate. Girls are overwhelmed with the intense degree of perceived sexual competition that exists in the digital world.

A significant percentage of young women respond to competition pressure by dropping out, because they start to ask themselves: “Why?” Why try when the world, or what appears to be the world through the lens of the screen, is flooded with women who are inhumanly beautiful? How does one even begin to compete with that? Young women, themselves having exacting standards for male partners, tend to assume that men desire perfection, or something close to it. They scrutinize every aspect of their physicality, in the way they imagine a man would: “My waist could be smaller, my legs could be slimmer, my hips could be wider, my breasts could be fuller. My nose isn’t right, my lips aren’t right, my eyes aren’t right. How could anyone ever love something as disgusting as me?” Women are perpetually insecure and social media isn’t helping. Instead, it floods the digital landscape with images of stunning women. The effect? Women can’t help but feel that everyone is beautiful.

Everyone except themselves.

And though it is fashionable to despise male attention, women can’t help but secretly desire it. A lack of attention is a death sentence. Most women would rather be sexually harassed than ignored. In every complaint about male sexual attention lies a (not-so) secret brag. With the mainstreaming of feminist discourses, this is the primary way women can brag about their desirability; explicitly admitting a desire for male attention is the greatest taboo. The only thing worse than male attention, is no male attention at all

If I get more pretty

Do you think he will like me?

Dissect my insecurities

I'm a defect, surgical project

It's getting hard to breathe

There's plastic wrap in my cheeks

Maybe I should try harder

You should lower your beauty standards

I'm no quick-curl barbie

I was never cut out for prom queen”

— Beach Bunny, Prom Queen

And though it is fashionable to despise male attention, women can’t help but secretly desire it. A lack of attention is a death sentence. Most women would rather be sexually harassed than ignored.

Worse, some girls are ugly. Contending with ugliness as a young woman is a bitter and brutal process. Ugliness in women is an existential failure; at least, it feels that way when you’re thirteen years old and all of the boys like all of the other girls but ignore you. The ideal woman is, first and foremost, beautiful. Everything else is secondary. And this breeds a certain kind of powerlessness. Your appearance is, to a large extent, out of your control. Yes, you can exercise, maintain a slim figure. Yes, you can do your hair, and wear makeup, and dress nicely. But nothing can fix an unshapely nose, narrow hips, broad shoulders, a recessed jaw, or hollow eyes. And you may say, men don’t care! Men will love you anyways; men will desire you despite your flaws, they will find you attractive as long as you are slim and bubbly. But this is only partially reassuring. Because women don’t want to be just acceptably attractive, deep down, every woman wants to be Helen, beautiful enough to sink1 a thousand ships. Fantasizing about becoming beautiful, of waking up one day and having the world fall to your feet, is a desire for extraordinary power. Ugliness makes girls feel powerless.

Worse, some girls are ugly. Contending with ugliness as a young woman is a bitter and brutal process. Ugliness in women is an existential failure.

Being bombarded with images of extraordinarily gorgeous women demoralizes young girls. And demoralized girls stop trying. They quit. This is the other pathology motivating the trans-social contagion in young women. Most recently, Billie Eilish (a notable Gen-Z pop star), revealed that she never felt like a woman at all:

“I’ve never felt like a woman, to be honest with you. I’ve never felt desirable. I’ve never felt feminine. I have to convince myself that I’m, like, a pretty girl. I identify as ‘she/her’ and things like that, but I’ve never really felt like a girl.”

What is implicit in Eilish’s words is that primal association between womanhood and beauty, and how this association alienates insecure young women from womanhood. This is the distinct reason why the female pop stars young women tend to look up to, lack any form of sex appeal (despite maybe being conventionally attractive). A woman with a highly sexual presence is a threat, she is scary, she reminds them of their own inadequacy.

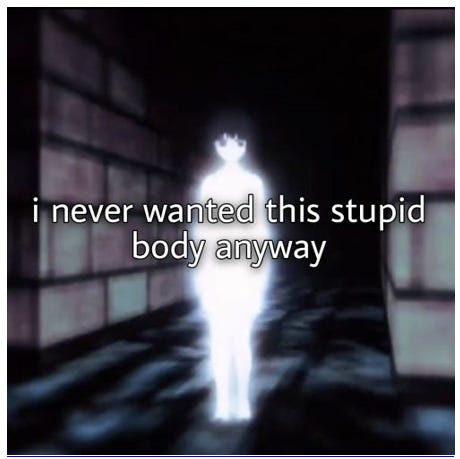

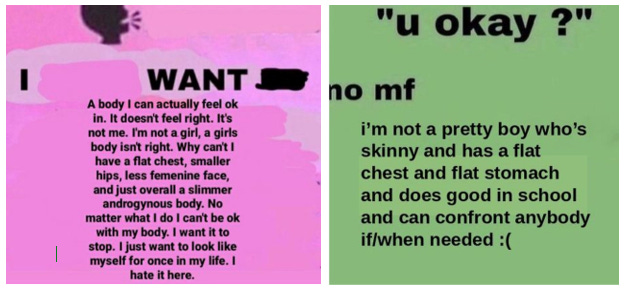

And when you are a particularly insecure young girl, being on the internet can feel as if you are being bombarded with reminders of your inadequacies. In this state, an escape from womanhood offers a way out. Modern trans-rhetoric is also uniquely adapted to exploiting these moments of insecurity within young women. Suggesting to them that any form of discomfort with a female body is a sign of not really being a woman, when in reality, feeling conflicted, at odds, and uneasy with your body is core to the female experience.

What is really strikingly obvious when perusing the social media content produced by FTMs for FTMs is the distinctly feminine perception the content reveals about the individual who created it:

Men do not talk about their bodies like this. Women do.

What is particularly insidious about the trans phenomenon is that any doubt an individual may have about their supposed trans identity is framed as a consequence of internalized transphobia. Online spaces such as this allow vulnerable young women to find comfort and solace in a community of like-minded peers. Unfortunately, these communities encourage young women to take actions that will only further alienate them from their bodies by reinforcing gender dysphoria, rather than coming to terms with it.

Modern trans-rhetoric is also uniquely adapted to exploiting these moments of insecurity within young women. Suggesting to them that any form of discomfort with a female body is a sign of not really being a woman, when in reality, feeling conflicted, at odds, and uneasy with your body is core to the female experience.

Feeling alienated from your body, disliking the male attention your body invites, secretly feeling a kind of thrill when your beauty benefits you, enjoying the power you hold over men: these are feelings girls commonly experience as they transition to womanhood.

In a healthy society, young girls eventually come to terms with these complex and somewhat contradictory feelings. This is not the case today. Today, young women are rewarded most for acting on their most pathological impulses. Platforms such as Instagram and OnlyFans incentivize some young women to profit from the male gaze to the detriment of their future well-being. On the other hand, for young women who feel alienated by their sexual desirability (or lack thereof), there exist a plethora of alternative online communities like FTM or pro-eating disorder spaces that offer young women refuge from the male gaze, while offering them emotional support and subcultural status.

What is not at all encouraged is coming to terms with the complex feelings womanhood induces within young girls, coming to terms with that mix of terror and thrill. This process is entirely disrupted by modern social norms. Why? Because sexual norms today skirt around one obvious, horrifying fact: women like being sex objects. That eighteen year old on OnlyFans? She’s not motivated by entrepreneurial drive, economic desperation, patriarchal socialization, or any such external factor we may want to point to. No, she simply likes the idea of being a hot commodity, of being so sexy that men would pay to see her. She likes being a whore. Acknowledging women’s innate desire to be sexualized, to be objectified, is sacrilegious; it is a truth conveniently avoided by both feminists and traditionalists alike. Instead, they posit that women’s behaviour is entirely downstream of that of men’s, that if men didn’t desire women so much, that if they stopped watching porn, stopped “objectifying women,” stopped having sex outside of marriage, that all sexual degeneracy would disappear. And so, male sexuality is criminalized, and female sexuality is conveniently ignored. And while this set of social norms preserves a rosy, hapless image of women, it harms young girls through its complete lack of social regulation of feminine sexual impulses. If you do not restrict female sexual impulses, what you get is a race to the bottom, with young girls intensely competing with each other for sexual attention. A lack of common sense limitations leads to a rise in things like unnecessary plastic surgeries, the proliferation of photoshop, hypersexual online personas. The digital landscape is flooded with images of inhumanly beautiful women. Intense sexual competition has adverse effects on other young girls by either encouraging them to adopt such behaviours, or by alienating them from womanhood entirely.

“Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it's all a male fantasy: that you're strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it. Even pretending you aren't catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you're unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

—Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride

Ultimately, what growing up means for girls, is coming to terms with the male gaze. The male gaze, contrary to the popular feminist conception of it, is not a product of patriarchal society. Rather, the voyeur in your own head is a native facet of feminine psychology. The voyeur in your head is awareness of your desirability, the power it holds, the danger it can bring; this awareness is crucial for women to have as they navigate the world around them.

The right amount of awareness is necessary, but too much of it can be paralyzing, suffocating, leading to pathological responses. This is the condition of young women today: hyper-self self-consciousness. Ideally, a young woman navigates the process of growing up and comes to terms with her status as sex-object, recognizing that this facet of existence is an inalienable part of her, but that she cannot be reduced to simply that; that yes, being beautiful is important, it is a means to power, but being beautiful is not the end itself. When this natural process of coming to terms with womanhood is disrupted, what you get is a generation of half-formed young women: stunted and scared.

This process is entirely disrupted by modern social norms. Why? Because sexual norms today skirt around one obvious, horrifying fact: women like being sex objects.

Our current culture supposedly encourages young women to grow and develop themselves. They say: “You can do anything!” But dig deeper, and what you will find is that this is hollow. You are told that you must aspire to a narrow set of politically correct ideals, and wanting anything else makes you a traitor to your sex. Most of all, under any circumstances, you cannot admit to wanting to be wanted. Deep down, what young women want more than anything else is to be loved and desired. An obvious fact that is too taboo for anyone to acknowledge.

Under the current feminist paradigm, women’s motivations must be desexed; made sterile. But refusing to acknowledge that it is in women’s nature to desire male validation does not make the desire go away. Repressing a fundamental instinct only means that it will make itself known in intensely destructive ways. Young women can only come to terms with coming of age when they can acknowledge that they desire male attention, and the baggage that comes along with that. And through acknowledging it, they can make a conscious decision about what to do about it: when to indulge the instinct, when not to, how to cope with feeling ugly, how to pursue beauty in a balanced way. But feminist norms have failed young women because feminists are far too afraid of confronting what it is that women really want. They offer no guidance to young women beyond telling them to either mindlessly indulge all their desires under the guise of empowerment, or to unlearn their deepest desires under the guise that they are merely products of patriarchal socialization. This partially explains the paradoxical fact that despite having access to unprecedented freedom, young women report unprecedented rates of unhappiness.

Why are young women today so deranged? Because no one is honest with them and they cannot be honest with themselves. Parents lie to you, teachers lie to you, friends lie to you, everyone lies to you. If anyone dares tell you the truth, they are ostracized. My teenage self could only find truth smuggled away in the dark recesses of obscure online communities; usually couched in layers of ironic (and sincere) bigotry. And while I did not enjoy the bigotry (at the time), I found value in engaging with the transgressive material I came across because I felt that it expressed truths otherwise unavailable to me. Today, truth lies within the domain of internet ghettos, siloed away from the rest of polite society. At best, what society tells you is entirely unhelpful: “You’re beautiful just the way you are.” At worst, what society tells you is entirely destructive: “If you feel alienated by your body, you should maybe consider a mastectomy.” I didn’t want to hear any of this and I didn’t need to hear any of this.

Why are young women today so deranged? Because no one is honest with them and they cannot be honest with themselves.

But no one told me anything I needed to hear. What I needed to hear was that it was okay: that it was okay for me to want to be pretty and for me to want boys to like me; that it was okay that I felt scared and uncomfortable with the way my body changed and with the way the world started to look at me; that it was okay that I felt ugly, and that I didn’t need to be the prettiest girl in the world, just the prettiest version of myself; that it was okay for me to aspire to things beyond a high-powered career; that it was okay for me to want to fall in love and for me to want to be a mother, that it didn’t make a traitor to my sex. I needed someone to tell me that it was okay for me to be a girl. And it was not just me that needed to hear that, other girls needed to hear it too, and they still do.

e-girl esoterica | zinnia | Substack

Some Acknowledgements: First, I would like to thank Edison Blake for seeing the potential in the half-finished draft that later became this piece, for (affectionately) bullying me into finishing it, and for tirelessly editing its many variations. Next, I would like to thank John Carter, for helping polish this piece, for tolerating my many abuses of the semicolon, and for generously offering to guest-publish this piece on his blog, Postcards From Barsoom (which partly inspired me to start writing).

Thank You for Being Part of Our Community

Your presence here is greatly valued. If you've found the content interesting and useful, please consider supporting it through a paid subscription. While all our resources are freely available, your subscription plays a vital role. It helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. Please make full use of our Free Libraries.

Discover Our Free Libraries:

Unbekoming Interview Library: Dive into a world of thought-provoking interviews across a spectrum of fascinating topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Explore concise summaries of groundbreaking books, distilled for efficient understanding.

Hear From Our Subscribers: Check out the [Subscriber Testimonials] to see the impact of this Substack on our readers.

Share Your Story or Nominate Someone to Interview:

I'm always in search of compelling narratives and insightful individuals to feature. Whether it's personal experiences with the vaccination or other medical interventions, or if you know someone whose story and expertise could enlighten our community, I'd love to hear from you. If you have a story to share, insights to offer, or wish to suggest an interviewee who can add significant value to our discussions, please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com. Your contributions and suggestions are invaluable in enriching our understanding and conversation.

Resources for the Community:

For those affected by COVID vaccine injury, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Discover 'Baseline Human Health': Watch and share this insightful 21-minute video to understand and appreciate the foundations of health without vaccination.

Books as Tools: Consider recommending 'Official Stories' by Liam Scheff to someone seeking understanding. Start with a “safe” chapter such as Electricity and Shakespeare and they might find their way to vaccination.

Your support, whether through subscriptions, sharing stories, or spreading knowledge, is what keeps this community thriving. Thank you for being an integral part of this journey.

Wow - phewww - thanks 4 sharing. Woodstock generation granny speechless in Chicago.

This essay deals very well with only part of the issue. Whilst 'boys looking at pretty girls who want to be looked at' is one aspect (amplified through social media technology), I propose that there are plenty of boys and girls who want to get to know 'the opposite sex' with a wider curiosity in mind than only sex. There is much to be discovered and enjoyed in platonic boy-girl relationships even when sexual attraction may be forever bubbling around in the background. Not all primal urges have to be acted on immediately. Delayed gratification has its advantages.