Never in history had such a small circle of interests, centered in London and New York, controlled so much of the entire world’s economic destiny. The Anglo-American financial establishment had resolved to use their oil power in a manner no one could have imagined possible. The very outrageousness of their scheme was to their advantage, they clearly reckoned. - Engdahl

Imagine if they taught A Century of War by William Engdahl in high school.

Empire would never teach that.

I remember reading The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William Shirer a long time ago. It’s at least four times as long. Most definitely written by the victors.

Every single chapter of Engdahl’s book renovates a different room in my brain.

This stack is about Chapter Nine.

There is so much here.

If you still have any doubts about what a small group of powerful men, can do behind closed doors, this chapter should sweep them away.

I came to see the 1970s two “oil shocks” very differently. Any notion that these were organic events, and parts of “cycles” is dispelled.

You will see and understand the Green Agenda for what it truly is, certainly what it was birthed for (it has been repurposed). It is the psychopathic child of Big Oil. We could name it Kevin, and we most definitely need to talk about him.

I finally understand why there is so much anti-nuclear hysteria in the world. What the origin of that denialism is.

Other things that were reframed for me, were Yom Kippur, Iran and its Shah, Kissinger and ultimately The Bilderberg Group.

I had a good handle already on NSSM 200 but I’m glad Engdahl covers it well and plugs it into the broader context of the time.

As I was reading it, I thought about who WASN’T in the room.

In May of 1973, when 84 men got together and decided to increase the world’s oil price by 400%, there were no Presidents or Prime Ministers in the room, no, only people with real power were there.

Replaceable Uniparty figureheads are not needed for Empire’s real discussions.

And this was in the 1970s.

Decided, planned and executed to perfection.

Image their power today.

Which is why the word “Leak” annoys me so much.

Far too many people on our side still talk about a “Lab Leak”.

An accident.

Yes, an accident that evil people took advantage of, but still an accident. A leak.

Can anyone really still believe that these people needed an underpaid, overworked Chinese lab technician to forget to wash her hands before going home to feed her child, to “opportunistically” take advantage of the “leak” and have their “pandemic” and launch their global genetic?

Really?

Anyway…I’m incredibly grateful to Engdahl for explaining to me just how these psychopaths go about their business.

A Century of War by F. William Engdahl

Chapter 9

Running the World Economy in Reverse: Who Made the 1970s Oil Shocks?

NIXON PULLS THE PLUG

By the end of President Richard Nixon’s first year in office, 1969, the U.S. economy had again gone into recession. By 1970, in order to combat the downturn, U.S. interest rates had been sharply lowered. As a consequence, speculative ‘hot money’ began once again to leave the dollar in record amounts; higher short-term profits were sought in Europe and elsewhere.

One result of the by now almost decade-long American refusal to devalue the dollar, and her reluctance to take serious action to control the huge unregulated Eurodollar market, was an increasingly unstable short-term currency speculation. As most of the world’s bankers well knew, King Canute could pretend to hold the waves back for only so long.

As a result of Nixon’s expansionary domestic U.S. monetary policy in 1970, the capital inflows of the previous year were reversed, and the United States incurred a net capital outflow of $6.5 billion. But the U.S. recession persisted. As interest rates continued to drop into 1971 and the money supply to expand, these outflows reached huge dimensions, totaling $20 billion. Furthermore, in May 1971 the United States recorded its first monthly trade deficit, triggering a virtually international panic sell-off of the U.S. dollar. The situation was indeed becoming desperate.

By 1971, U.S. official gold reserves represented less than a quarter of her official liabilities: theoretically, if all foreign dollar holders demanded gold instead, Washington would have been unable to comply without taking drastic measures.1

The Wall Street establishment persuaded President Nixon to abandon fruitless efforts to hold the dollar against a flood of international demand to redeem dollars for gold. But, unfortunately, Wall Street did not want the required dollar devaluation against gold, which had been intensely sought for almost a decade.

On August 15, 1971, Nixon took the advice of a close circle of key advisers that included his chief budget adviser, George Shultz, and a policy group then at the Treasury Department, including Paul Volcker and Jack F. Bennett, who later went on to become a director of Exxon. That quiet, sunny August day, in a move which rocked the world, the president of the United States announced formal suspension of dollar convertibility into gold, effectively putting the world fully onto a dollar standard with no gold backing, thereby unilaterally ripping apart the central provision of the 1944 Bretton Woods system. No longer could foreign holders of U.S. dollars redeem their paper for U.S. gold reserves.

Nixon’s unilateral action was reaffirmed in protracted international talks that December in Washington between the leading European governments, Japan, and a few others, which resulted in a poor compromise known as the Smithsonian agreement. With an exaggeration which exceeded even that of his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, Nixon announced after the Smithsonian talks that they were ‘the conclusion of the most significant monetary agreement in the history of the world.’ The United States had formally devalued the dollar a mere 8 per cent against gold, placing gold at $38 per fine ounce instead of the long-standing $35—hardly the 100 per cent devaluation being asked for by her allies. The agreement also officially permitted a band of currency-value fluctuation of 2.25 per cent, instead of the original 1 per cent of the IMF Bretton Woods rules.

By declaring to world dollar holders that their paper would no longer be redeemed for gold, Nixon ‘pulled the plug’ on the world economy, setting into motion a series of events which was to rock the world as never before. Within weeks, confidence in the Smithsonian agreement had begun to collapse. De Gaulle’s defiance of Washington in April 1968 on the issue of gold and adherence to the rules of Bretton Woods had not been sufficient to force through the badly needed reordering of the international monetary system, but it had sufficiently poisoned the well of Washington’s ill-conceived IMF Special Drawing Rights scheme to obscure the problems of the dollar. The suspension of gold redemption and the resulting international ‘floating exchange rates’ of the early 1970s solved nothing. It only bought some time.

An eminently workable solution would have been for the United States to set the dollar to a more realistic level. From France, de Gaulle’s former economic adviser, Jacques Rueff, continued to plead for a $70 per ounce gold price, instead of the $35 level the U.S. unsuccessfully defended. This, Rueff argued, would calm world speculation and allow the U.S. to redeem her destabilizing Eurodollar balances abroad, without plunging the domestic U.S. economy into severe chaos. If done properly, this could have given a tremendous spur to U.S. industry, since its exports would have cost less in foreign currency. American industrial interests would again have predominated over financial voices in U.S. policy circles. But reason did not prevail. The Wall Street rationale was that the power of their financial domain must be untouched, even if this was at the expense of economic production or American national prosperity.

Gold itself has little intrinsic value. It has certain industrial uses. But historically, because of its scarcity, it has served as a standard of value against which different nations have fixed the terms of their trade and therefore their currencies. When Nixon decided no longer to honor U.S. currency obligations in gold, he opened the floodgates to a worldwide Las Vegas speculation binge of a dimension never before experienced in history. Instead of calibrating long-term economic affairs to fixed standards of exchange, after August 1971 world trade was simply another arena of speculation about the direction in which various currencies would fluctuate.

The real architects of the Nixon strategy were in the influential City of London merchant banks. Sir Siegmund Warburg, Edmond de Rothschild, Jocelyn Hambro and others saw a golden opportunity in Nixon’s dissolution of the Bretton Woods gold standard that summer of 1971. London was once again to become a major center of world finance, and again on ‘borrowed money,’ this time American Eurodollars.

After August 1971, the dominant U.S. policy under the White House national security adviser, Henry A. Kissinger, was to control, not to develop, economies throughout the world. U.S. policy officials began proudly calling themselves ‘neo-Malthusians.’ Population reduction in developing nations, rather than technology transfer and industrial growth strategies, became the dominating priority during the 1970s, yet another throwback to nineteenth-century British colonial thinking. How this transformation took place we shall soon see.

The ineffective basis of the Smithsonian agreement led to further deterioration into 1972, as massive capital flows again left the dollar for Japan and Europe, until February 12, 1973, when Nixon finally announced a second devaluation of the dollar, of 10 per cent against gold, pricing gold where it remains to this day for the Federal Reserve, at $42.22 per ounce.

At this point all the major world currencies began a process of what was called the ‘managed float.’ Between February and March 1973, the value of the U.S. dollar against the German Deutschmark dropped another 40 per cent. Permanent instability had been introduced into world monetary affairs in a way not seen since the early 1930s, but this time strategists in New York, Washington and the City of London were preparing an unexpected surprise to regain the upper hand and recover from the devastating loss of the monetary pillar of their system.

AN UNUSUAL MEETING AT SALTSJÖBADEN

The design behind Nixon’s August 15, 1971, dollar strategy did not emerge until October 1973, more than two years later, and even then, few persons other than a handful of insiders grasped the connection. The August 1971 demonetization of the dollar was used by the London–New York financial establishment to buy precious time, while policy insiders prepared a bold new monetarist design, a ‘paradigm shift’ as some preferred to term it. Certain influential voices in the Anglo-American financial establishment had devised a strategy to create again a strong dollar, and once again to increase their relative political power in the world, just when it appeared they were in a decisive rout.

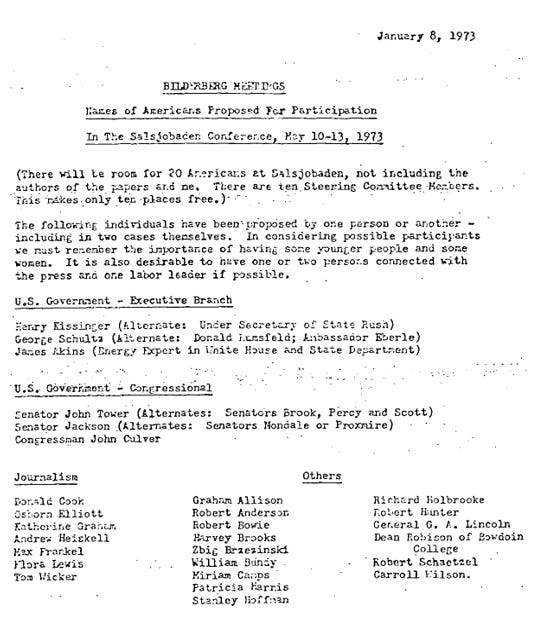

Figure 4 Memo of January 8, 1973, from U.S. Bilderberg official Robert D. Murphy, containing the United States’ proposed list of May 1973 participants, including Henry Kissinger. The memo is amongst Murphy’s papers at the Hoover Institute.

In May 1973, with the dramatic fall of the dollar still vivid, a group of 84 of the world’s top financial and political insiders met at Saltsjöbaden, Sweden, the secluded island resort of the Swedish Wallenberg banking family. This gathering of Prince Bernhard’s Bilderberg group heard an American participant, Walter Levy, outline a ‘scenario’ for an imminent 400 per cent increase in OPEC petroleum revenues. The purpose of the secret Saltsjöbaden meeting was not to prevent the expected oil price shock, but rather to plan how to manage the about-to-be-created flood of oil dollars, a process U.S. Secretary of State Kissinger later called ‘recycling the petrodollar flows.’

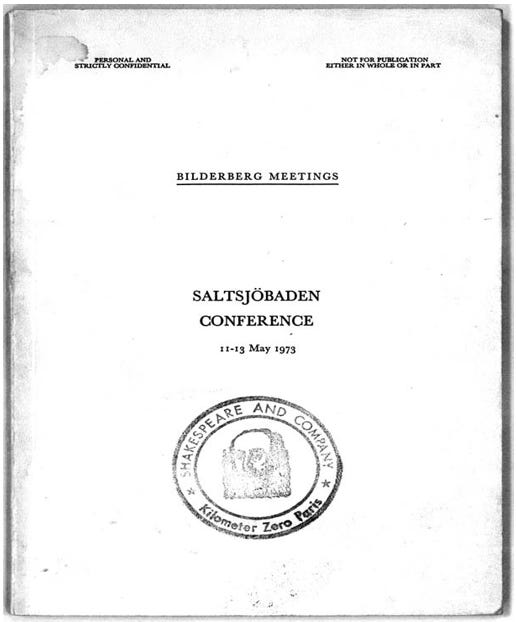

Figure 5 Cover page of the confidential protocol of the 1973 Bilderberg meeting at Saltsjöbaden. The page bears the stamp of the Paris bookseller from whom the minutes were bought by the author.

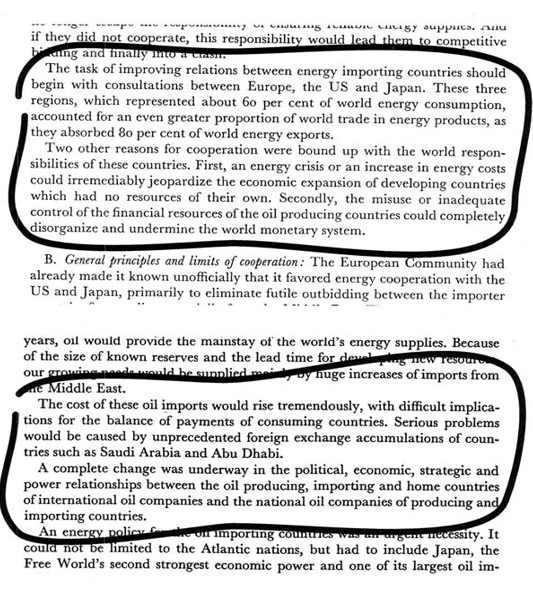

Figure 6-7 Two excerpts from the confidential protocol of the May 1973 meeting of the Bilderberg group at Saltsjöbaden, Sweden. Note that there was discussion about the danger that ‘inadequate control of the financial resources of the oil producing countries could completely disorganize and undermine the world monetary system.’ The second excerpt speaks of ‘huge increases of imports from the Middle East. The cost of these imports would rise tremendously.’ Figures given later in the discussion show a projected price rise for OPEC oil of some 400 per cent.

The American speaker to the Bilderberg on Atlantic–Japanese energy policy, was clear enough. After stating the prospect that future world oil needs would be supplied by a small number of Middle East producing countries, the speaker declared, prophetically: ‘The cost of these oil imports would rise tremendously, with difficult implications

for the balance of payments of consuming countries. Serious problems would be caused by unprecedented foreign exchange accumulations of countries such as Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi.’ The speaker added, ‘A complete change was underway in the political, strategic and power relationships between the oil producing, importing and home countries of international oil companies and national oil companies of producing and importing countries.’ He then projected an OPEC Middle East oil revenue rise, which would translate into just over 400 per cent, the same level Kissinger was soon to demand of the Shah.

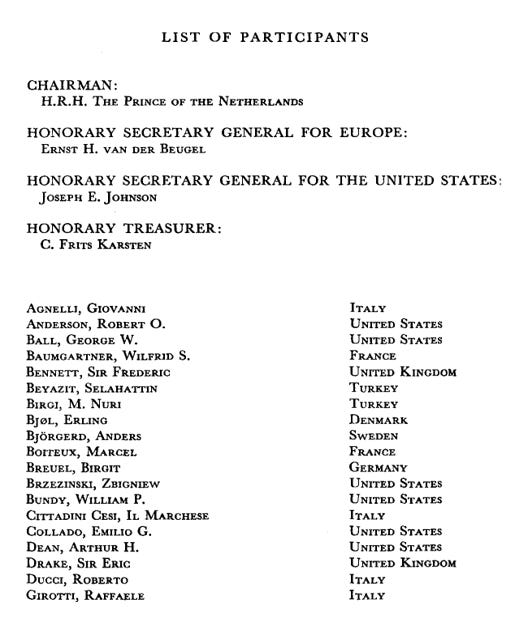

Figure 8 Partial list of official attendees at the 1973 Bilderberg meeting. It includes ARCO head Robert O. Anderson, Zbigniew Brzezinski and George Ball.

Present at Saltsjöbaden that May were Robert O. Anderson of Atlantic Richfield Oil Co.; Lord Greenhill, chairman of British Petroleum; Sir Eric Roll of S.G. Warburg, creator of Eurobonds; George Ball of Lehman Brothers investment bank, and the man who some ten years earlier, as assistant secretary of state, told his banker friend Siegmund Warburg to develop London’s Eurodollar market; David Rockefeller of Chase Manhattan Bank; Zbigniew Brzezinski, the man soon to be President Carter’s national security adviser; Italy’s Gianni Agnelli and Germany’s Otto Wolff von Amerongen, among others. Henry Kissinger was a regular participant at the Bilderberg gatherings.

The Bilderberg annual meetings were initiated, in the utmost secrecy, in May 1954 by an Anglophile group which included George Ball, David Rockefeller, Dr. Joseph Retinger, Holland’s Prince Bernhard and George C. McGhee (then of the U.S. State Department and later a senior executive of Mobil Oil). Named for the place of their first gathering, the Hotel de Bilderberg near Arnheim, the annual Bilderberg meetings gathered top elites of Europe and America for secret deliberations and policy discussion. Consensus was then ‘shaped’ in subsequent press comments and media coverage, but never with reference to the secret Bilderberg talks themselves. This Bilderberg process has been one of the most effective vehicles of postwar Anglo-American policy shaping.

What the powerful men grouped around Bilderberg had evidently decided that May was to launch a colossal assault against industrial growth in the world, in order to tilt the balance of power back to the advantage of Anglo-American financial interests and the dollar. In order to do this, they determined to use their most prized weapon— control of the world’s oil flows. Bilderberg policy was to trigger a global oil embargo, in order to force a dramatic increase in world oil prices. Since 1945, world oil had by international custom been priced in dollars, since American oil companies dominated the postwar market. A sudden sharp increase in the world price of oil, therefore, meant an equally dramatic increase in world demand for U.S. dollars to pay for that necessary oil.

Never in history had such a small circle of interests, centered in London and New York, controlled so much of the entire world’s economic destiny. The Anglo-American financial establishment had resolved to use their oil power in a manner no one could have imagined possible. The very outrageousness of their scheme was to their advantage, they clearly reckoned.

DR. KISSINGER’S YOM KIPPUR OIL SHOCK

On October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria invaded Israel, igniting what became known as the Yom Kippur War. Contrary to popular impression, the ‘Yom Kippur’ War was not the simple result of miscalculation, blunder or an Arab decision to launch a military strike against the state of Israel. The entire constellation of events surrounding the outbreak of the October War was secretly orchestrated by Washington and London, using the powerful secret diplomatic channels developed by Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. Kissinger effectively controlled the Israeli policy response through his intimate relation with Israel’s Washington ambassador, Simcha Dinitz. In addition, Kissinger cultivated channels to the Egyptian and Syrian side. His method was simply to misrepresent to each party the critical elements of the other, ensuring the war and its subsequent Arab oil embargo.

U.S. intelligence reports, including intercepted communications from Arab officials confirming the buildup for war, were firmly suppressed by Kissinger, who was by then Nixon’s intelligence ‘czar.’ The war and its aftermath, Kissinger’s infamous ‘shuttle diplomacy,’ were scripted in Washington along the precise lines of the Bilderberg deliberations in Saltsjöbaden the previous May, some six months before the outbreak of the war. Arab oil-producing nations were to be the scapegoats for the coming rage of the world, while the Anglo- American interests responsible stood quietly in the background.

In mid October 1973, the German government of Chancellor Willy Brandt told the U.S. ambassador to Bonn that Germany was neutral in the Middle East conflict, and would not permit the United States to resupply Israel from German military bases. With an ominous foreshadowing of similar exchanges which would occur some 17 years later, Nixon, on October 30, 1973, sent Chancellor Brandt a sharply worded protest note, most probably drafted by Kissinger:

We recognize that the Europeans are more dependent upon Arab oil than we, but we disagree that your vulnerability is decreased by disassociating yourselves from us on a matter of this importance … You note that this crisis was not a case of common responsibility for the Alliance, and that military supplies for Israel were for purposes which are not part of Alliance responsibility. I do not believe we can draw such a fine line …

Washington would not permit Germany to declare its neutrality in the Middle East conflict. But, significantly, Britain was allowed to clearly state its neutrality, thus avoiding the impact of the Arab oil embargo. Once again, London had skillfully maneuvered itself around an international crisis that it had been instrumental in precipitating. One enormous consequence of the ensuing 400 per cent rise in OPEC oil prices was that investments of hundreds of millions of dollars by British Petroleum, Royal Dutch Shell and other Anglo-American petroleum concerns in the risky North Sea could produce oil at a profit. It is a curious fact of the time that the profitability of these new North Sea oilfields was not at all secure until after the OPEC price rises. Of course, this might only have been a fortuitous coincidence.

By October 16, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, following a meeting on oil prices in Vienna, had raised their price by a staggering 70 per cent, from $3.01 to $5.11 per barrel. That same day, the members of the Arab OPEC countries, citing the U.S. support for Israel in the Middle East war, declared an embargo on all oil sales to the United States and the Netherlands—Rotterdam being the major oil port of western Europe.

Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Libya, Abu Dhabi, Qatar and Algeria announced on October 17, 1973, that they would cut their production below the September level by 5 per cent for October and an additional 5 per cent per month, ‘until Israeli withdrawal is completed from the whole Arab territories occupied in June 1967 and the legal rights of the Palestinian people are restored.’ The world’s first ‘oil shock,’ or as the Japanese termed it, ‘Oil Shokku’ was underway.

Significantly, the oil crisis hit full force in late 1973, just as the president of the United States was becoming personally embroiled in what came to be called the ‘Watergate affair,’ leaving Henry Kissinger as de facto president, running U.S. policy during the crisis.

When the Nixon White House sent a senior official to the U.S. Treasury in 1974 in order to devise a strategy to force OPEC into lowering the oil price, he was bluntly turned away. In a memo, the official stated, ‘It was the banking leaders who swept aside this advice and pressed for a “recycling” program to accommodate to higher oil prices. This was the fatal decision …’

The U.S. Treasury, under Jack Bennett, the man who had helped steer Nixon’s fateful August 1971 dollar policy, had established a secret accord with the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, SAMA, finalized in a February 1975 memo from U.S. Assistant Treasury Secretary Jack F. Bennett to Secretary of State Kissinger. Under the terms of the agreement, a sizeable part of the huge new Saudi oil revenue windfall was to be invested in financing the U.S. government deficits. A young Wall Street investment banker with the leading London-based Eurobond firm of White Weld & Co., David Mulford, was sent to Saudi Arabia to become the principal ‘investment adviser’ to SAMA; he was to guide the Saudi petrodollar investments to the correct banks, naturally in London and New York. The Bilderberg scheme was operating just as planned.

Kissinger, as Nixon’s all-powerful national security adviser already firmly in control of all U.S. intelligence estimates, secured control of U.S. foreign policy as well, persuading Nixon to name him secretary of state in the weeks just prior to the outbreak of the October Yom Kippur War. Indicative of his central role in events, Kissinger retained both titles, as head of the White House National Security Council and as secretary of state, something no other individual has ever done, before or since. No other single person during the last months of the Nixon presidency wielded as much absolute power as did Henry Kissinger. To add insult to injury, Kissinger was given the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize.

Following a meeting in Teheran on January 1, 1974, a second price increase of more than 100 per cent brought OPEC benchmark oil prices to $11.65. This was done on the surprising demand of the Shah of Iran, who had been secretly put up to it by Henry Kissinger. Only months earlier, the Shah had opposed the OPEC increase to

$3.01 for fear that this would force Western exporters to charge more for the industrial equipment the Shah sought to import for Iran’s ambitious industrialization. The support of Washington and the West for Israel in the October War had fed OPEC anger at the meetings. Even Kissinger’s own State Department had not been informed of his secret machinations with the Shah.6

From 1949 until the end of 1970, Middle East crude oil prices had averaged approximately $1.90 per barrel. They had risen to $3.01 in early 1973, at the time of the fateful Saltsjöbaden meeting of the Bilderberg group, which discussed an imminent 400 per cent future rise in OPEC’s price. By January 1974, that 400 per cent increase was a fait accompli.

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE OIL SHOCK

The social impact of the oil embargo on the United States in late 1973 could be described as panic. Throughout 1972 and early 1973, the large multinational oil companies, led by Exxon, had pursued a curious policy of creating a short supply of domestic crude oil. They were allowed to do this under an unusual series of decisions made by President Nixon on the advice of his aides. When the embargo hit in November 1973, therefore, the impact could not have been more dramatic. At the time, the White House was responsible for controlling U.S. oil imports under the provisions of a 1959 U.S. trade agreements act.

In January 1973, Nixon had appointed Treasury Secretary George Shultz to be assistant to the president for economic affairs as well. In this post, Shultz oversaw White House oil import policy. His deputy treasury secretary, William E. Simon, a former Wall Street bond trader, was made chairman of the important Oil Policy Committee, which determined U.S. oil import supply in the critical months leading up to the October embargo.

In February 1973, Nixon was persuaded to set up a special ‘energy triumvirate,’ which included Shultz, White House aide John Ehrlichman, and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, to be known as the White House Special Energy Committee. The scene was quietly being set for the Bilderberg plan, though almost no one in Washington or elsewhere realized the fact. By October 1973, U.S. stocks of domestic crude oil were already at alarmingly low levels. The OPEC embargo triggered panic buying of gasoline among the public, calls for rationing, endless gas lines and a sharp economic recession.

The most severe impact of the oil crisis was on the United States’ largest city, New York. In December 1974, nine of the world’s most powerful bankers, led by David Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan, Citibank, and the London–New York investment bank, Lazard Freres, told New York Mayor Abraham Beame, an old-line machine politician, that unless he turned over control of the city’s huge pension funds to a committee of the banks, the Municipal Assistance Corporation, the banks and their influential friends in the media would ensure the financial ruin of the city. Not surprisingly, the overpowered mayor capitulated and New York City was forced to slash spending for roadways, bridges, hospitals and schools in order to service their bank debt, and to lay off tens of thousands of city workers. The nation’s greatest city had begun its descent into a scrap heap. Felix Rohatyn of Lazard Freres became head of the new bankers’ collection agency, dubbed ‘Big MAC’ by the press.

In western Europe, the shock of the oil price rise and the embargo on supplies was equally dramatic. From Britain to the Continent, country after country felt the effects of the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. Bankruptcies and unemployment across Europe rose to alarming levels.

Germany’s government imposed an emergency ban on Sunday driving, in a desperate effort to save imported oil costs. By June 1974, the effects of the oil crisis had contributed to the dramatic collapse of Germany’s Herstatt-Bank and a crisis in the Deutschmark as a result. As Germany’s imported oil costs increased by a staggering 17 billion Deutschmarks in 1974, with half a million people reckoned to be unemployed due to the effects of the oil crisis, inflation levels reached an alarming 8 per cent. The shock effects of a sudden 400 per cent increase in the price of Germany’s basic energy feedstock were devastating to industry, transport, and agriculture. Key industries such as steel, shipbuilding and chemicals went into a deep crisis.

Willy Brandt’s government was effectively defeated by the domestic impact of the oil crisis, as much as by the revelations of the Stasi affair against his close adviser, Günther Guillaume. By May 1974, Brandt had offered his resignation to Federal President Heinemann, who then appointed Helmut Schmidt as chancellor. Most of the governments of Europe fell during this period, victims of the consequences of the oil crisis on their economies.

But for the less developed economies of the world, the impact of an overnight price increase of 400 per cent in their primary energy source was staggering. The vast majority of the world’s less developed economies, without significant domestic oil resources, were suddenly confronted with an unexpected and unpayable 400 per cent increase in the cost of energy imports, to say nothing of the cost of chemicals and fertilizers derived from petroleum. During this time, commentators began speaking of ‘triage,’ the wartime idea of survival of the fittest, and introduced the vocabulary of ‘Third World’ and ‘Fourth World’ (the non-OPEC countries).

India in 1973 had a positive balance of trade, a healthy situation for a developing economy. But by 1974, India had total foreign exchange reserves of $629 millions with which to pay—in dollars—an annual oil import bill of almost double that, or $1,241 million. Sudan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand and country after country throughout Africa and Latin America were faced in 1974 with gaping deficits in their balance of payments. According to the IMF, developing countries in 1974 incurred a total trade deficit of $35 billion, a colossal sum in that day, and, not surprisingly, a deficit four times as large as in 1973—precisely in proportion to the oil price increase. Following the several years of strong industrial and trade growth of the early 1970s, the severe drop in industrial activity throughout the world economy in 1974–75 was greater than any such decline since the war.

But while Kissinger’s 1973 oil shock had a devastating impact on world industrial growth, it had an enormous benefit for certain established interests—the major New York and London banks, and the Seven Sisters oil multinationals of the United States and Britain. By 1974, Exxon had overtaken General Motors as the largest American corporation in gross revenues. Her sisters, including Mobil, Texaco, Chevron and Gulf, were not far behind.

The bulk of the OPEC dollar revenues, Kissinger’s ‘recycled petrodollars,’ was deposited with the leading banks of London and New York, the banks which dealt in dollars as well as international oil trade. Chase Manhattan, Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover, Bank of America, Barclays, Lloyds, Midland Bank—all enjoyed the windfall profits of the oil crisis. We shall later see how they recycled their petrodollars during the 1970s, and how this set the stage for the great debt crisis of the 1980s.

TAKING THE ‘BLOOM OFF THE NUCLEAR ROSE’

One principal concern of the authors of the 400 per cent oil price increase was how to ensure that their drastic action would not drive the world to accelerate an already strong trend towards the construction of a far more efficient and ultimately less expensive alternative energy source—nuclear electricity generation.

Kissinger’s former dean at Harvard, and his boss when Kissinger briefly served as a consultant to John Kennedy’s National Security Council, was McGeorge Bundy. Bundy left the White House in 1966 in order to play a critical role in shaping the domestic policy of the United States as president of the largest private foundation, the Ford Foundation. By December 1971, Bundy had established a major new project for the foundation, the Energy Policy Project, under the direction of S. David Freeman, and with an impressive $4 million checkbook and a three-year time limit. Bundy’s Ford study, titled ‘A Time to Choose: America’s Energy Future,’ was released in the midst of the debate during the 1974 oil crisis. It was to shape the public debate in the critical time of the oil crisis.

For the first time in American establishment circles, the fraudulent thesis was proclaimed that ‘Energy growth and economic growth can be uncoupled; they are not Siamese twins.’ Freeman’s study advocated bizarre and demonstrably inefficient ‘alternative’ energy sources such as wind power, solar reflectors and burning recycled waste. The Ford report made a strong attack on nuclear energy, arguing that the technologies involved could theoretically be used to make nuclear bombs. ‘The fuel itself or one of the byproducts, plutonium, can be used directly or processed into the material for nuclear bombs or explosive devices,’ the report asserted.

The Ford study correctly noted that the principal competitor to the hegemony of petroleum in the future was nuclear energy, warning against the ‘very rapidity with which nuclear power is spreading in all parts of the world and by development of new nuclear technologies, most notably the fast breeder reactors and the centrifuge method of enriching uranium.’ The framework of the U.S. financial establishment’s antinuclear ‘green’ assault had been defined by Bundy’s project.9

By the early 1970s, nuclear technology had clearly established itself as the preferred future choice for efficient electricity generation, vastly more efficient (and environmentally friendly) than either oil or coal. At the time of the oil shock, the European Community was already well into a major nuclear development program. As of 1975, the plans of member governments called for the completion of between 160 and 200 new nuclear plants across Continental Europe by 1985.

In 1975, the Schmidt government in Germany, reacting rationally to the implications of the 1974 oil shock, passed a program which called for an added 42 gigawatts of German nuclear plant capacity, to produce a total of approximately 45 per cent of German total electricity demand by 1985, a program exceeded in the EC only by France’s, which projected 45 gigawatts of new nuclear capacity by 1985. In the fall of 1975, Italy’s industry minister, Carlo Donat Cattin, instructed Italy’s nuclear companies, ENEL and CNEN, to draw up plans for the construction of some 20 nuclear plants for completion by the early 1980s. Even Spain, just then emerging from four decades of Franco’s rule, had a program calling for the construction of 20 nuclear plants by 1983. A typical 1 gigawatt nuclear facility is generally sufficient to supply all the electricity requirements for a modern industrial city of 1 million people.

The rapidly growing nuclear industries of Europe, especially France and Germany, were beginning for the first time to emerge as competent rivals to American domination of the nuclear export market by the time of the 1974 oil crisis. France had secured a Letter of Intent from the Shah of Iran, as had Germany’s KWU, to build a total of four nuclear reactors in Iran, while France had signed with Pakistan’s Bhutto government to create a modern nuclear infrastructure in that country. Negotiations between the German government and Brazil also reached a successful conclusion in February 1976, for cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. This included German construction of eight nuclear reactors as well as facilities for reprocessing and enriching uranium reactor fuel. German and French nuclear companies, with the full support of their governments, entered in this period into negotiations with select developing sector countries, fully in the spirit of Eisenhower’s 1953 Atoms for Peace declaration. Clearly, the Anglo-American energy grip, based on their tight control of the world’s major energy source, petroleum, was threatened if these quite feasible programs went ahead.

In the postwar period, nuclear energy represented precisely the same technological improvement over oil which oil had represented over coal when Lord Fisher and Winston Churchill argued at the end of the nineteenth century that Britain’s navy should convert to oil from coal. The major difference in the 1970s was that Britain and her cousins in the United States were firmly in control of world oil supplies. World nuclear technology threatened to open unbounded energy possibilities, especially if plans for commercial nuclear fast breeder reactors were realized, as well as for thermonuclear fusion.

In the immediate aftermath of the 1974 oil shock, two organizations were established within the nuclear industry, both, significantly enough, based in London. In early 1975, an informal semisecret group was established, the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group, or ‘London Club,’ as it was known. The group included Britain, the United States and Canada, together with France, Germany, Japan and the USSR. This was an initial Anglo-American effort to secure self-restraint on nuclear export. This group was complemented in May 1975 by the formation of another secretive organization, the London ‘Uranium Institute,’ which brought together the world’s major suppliers of uranium. This was dominated by the traditional British territories, including Canada, Australia, South Africa and the United Kingdom. These ‘inside’ organizations were necessary, but by no means sufficient, for the Anglo-American interests to contain the nuclear ‘threat’ of the early 1970s. As one prominent antinuclear American from the Aspen Institute put it, ‘We must take the bloom off the “nuclear rose.”’ And take it off they did.

DEVELOPING THE ANGLO-AMERICAN GREEN AGENDA

It was no accident that, following the oil shock recession of 1974– 75, a growing part of the population of western Europe, especially in Germany, began talking for the first time in the postwar period about ‘limits to growth,’ or threats to the environment, and began to question their faith in the principle of industrial growth and technological progress. Very few people realized the extent to which their new ‘opinions’ were being carefully manipulated from the top by a network established by the same Anglo-American finance and industry circles that lay behind the Saltsjöbaden oil strategy.

Beginning in the 1970s, an awesome propaganda offensive was launched from select Anglo-American think tanks and journals, intended to shape a new ‘limits to growth’ agenda, which would ensure the ‘success’ of the dramatic oil shock strategy. The American oilman present at the May 1973 Saltsjöbaden meeting of the Bilderberg group, Robert O. Anderson, was a central figure in the implementation of the ensuing Anglo-American ecology agenda. It was to become one of the most successful frauds in history.

Anderson and his Atlantic Richfield Oil Co. funneled millions of dollars through their Atlantic Richfield Foundation into select organizations to target nuclear energy. One of the prime beneficiaries of Anderson’s largesse was a group called Friends of the Earth, which was organized in this time with a $200,000 grant from Anderson. One of the earliest actions of Anderson’s Friends of the Earth was an assault on the German nuclear industry, through such antinuclear actions as the anti-Brockdorf demonstrations in 1976, led by Friends of the Earth leader Holger Strohm. The director of Friends of the Earth in France, Brice Lalonde, was the Paris partner of the Rockefeller family law firm Coudert Brothers, and became Mitterrand’s environment minister in 1989. It was Friends of the Earth which was used to block a major Japanese–Australian uranium supply agreement. In November 1974, Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka went to Canberra to meet Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. The two made a commitment, potentially worth billions of dollars, for Australia to supply Japan’s needs for future uranium ore and enter a joint project to develop uranium enrichment technology. British uranium mining giant Rio Tinto Zinc secretly deployed Friends of the Earth in Australia to mobilize opposition to the pending Japanese agreement, resulting some months later in the fall of Whitlam’s government. Friends of the Earth had ‘friends’ in very high places in London and Washington.

But Robert O. Anderson’s major vehicle for spreading the new ‘limits to growth’ ideology among American and European establishment circles was his Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. With Anderson as chairman and Atlantic Richfield head Thornton Bradshaw as vice-chairman, the Aspen Institute in the early 1970s was a major financial conduit for the creation of the establishment’s new antinuclear agenda.

Among the better-known trustees of Aspen at this time was World Bank president and the man who ran the Vietnam war, Robert S. McNamara. Other carefully selected Aspen trustees included Lord Bullock of Oxford University, Richard Gardner, an Anglophile American economist who was later U.S. ambassador to Italy, Wall Street banker Russell Peterson of Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb Inc., as well as Exxon board member Jack G. Clarke, Gulf Oil’s Jerry McAfee and Mobil Oil director George C. McGhee, the former State Department official who was present in 1954 at the founding meeting of the Bilderberg group. Also involved with Anderson’s Aspen in this early period was Marion Countess Doenhoff, the Hamburg publisher of Die Zeit, as well as former Chase Manhattan Bank chairman and high commissioner to Germany, John J. McCloy.

Robert O. Anderson brought in Joseph Slater from McGeorge Bundy’s Ford Foundation to serve as Aspen’s president. It was indeed a close-knit family in the Anglo-American establishment of the early 1970s. The initial project Slater launched at Aspen was the preparation of an international organizational offensive against industrial growth and especially nuclear energy, using the auspices (and the money) of the United Nations. Slater secured support of Sweden’s UN ambassador, Sverker Aastrom, who, in the face of strenuous objections from developing countries, steered a proposal through the United Nations for an international conference on the environment.

From the outset, the June 1972 Stockholm UN Conference on the Environment was run by operatives of Anderson’s Aspen Institute. Aspen board member Maurice Strong, a Canadian oilman from Petro-Canada, chaired the Stockholm conference. Aspen also provided financing to create an international zero-growth network under UN auspices, the International Institute for Environment and Development, whose board included Robert O. Anderson, Robert McNamara, Strong and British Labour Party’s Roy Jenkins. The new organization immediately produced a book, Only One Earth, by Rockefeller University associate Rene Dubos and British Malthusian Barbara Ward (Lady Jackson). The International Chambers of Commerce were persuaded at this time to sponsor Maurice Strong and other Aspen figures in seminars targeting international businessmen on the emerging new environmentalist ideology.

The 1972 Stockholm conference created the necessary international organizational and publicity infrastructure, so that by the time of the Kissinger oil shock of 1973–74, a massive antinuclear propaganda offensive could be launched, with the added assistance of millions of dollars readily available from the oil-linked channels of the Atlantic Richfield Company, the Rockefeller Brothers’ Fund and other such elite Anglo-American establishment circles. Among the groups which were funded by these people at the time were organizations including the ultra-elitist World Wildlife Fund, then chaired by the Bilderberg’s Prince Bernhard and later by Royal Dutch Shell’s John Loudon.

Indicative of the financial establishment’s overwhelming influence in the American and British media is the fact that during this period no public outcry was heard about the probable conflict of interest involved in Robert O. Anderson’s well-financed antinuclear offensive, and the fact that his Atlantic Richfield Oil Co. was one of the major beneficiaries from the 1974 price increase of oil. Anderson’s ARCO had invested tens of millions of dollars in high-risk oil infrastructure in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay and Britain’s North Sea, together with Exxon, British Petroleum, Shell and the other Seven Sisters.

Had the 1974 oil crisis not raised the market price of oil to $11.65 per barrel or thereabouts, Anderson’s investments in the North Sea and Alaska, as well as those of British Petroleum, Exxon and the others, would have brought financial ruin. To ensure a friendly press voice in Britain, Anderson at this time purchased the London Observer. Virtually no one asked if Anderson and his influential friends might have known in advance that Kissinger would create the conditions for a 400 per cent oil price rise.

So as not to leave any zero-growth stone unturned, Robert O. Anderson also contributed significant funds to a project initiated by the Rockefeller family at the Rockefeller’s estate at Bellagio, Italy, with Aurelio Peccei and Alexander King. In 1972, this Club of Rome, and the U.S. Association of the Club of Rome, gave widespread publicity to their publication of a scientifically fraudulent computer simulation prepared by Dennis Meadows and Jay Forrester, titled ‘Limits to Growth.’ Meadows and Forrester added modern computer graphics to the discredited essay of Malthus, insisting that the world would soon perish for lack of adequate energy, food and other resources. As did Malthus, they chose to ignore the impact of technological progress on improving the human condition. Their message was one of unmitigated gloom and cultural pessimism.

One of the most targeted countries for this new Anglo-American antinuclear offensive was Germany. While France’s nuclear program was equally if not more ambitious, Germany was deemed an area where Anglo-American intelligence assets had greater likelihood of success, given their history in the postwar occupation of the Federal Republic. Almost as soon as the ink had dried on the Schmidt government’s 1975 nuclear development program, an offensive was launched.

A key operative in this new project was a young woman with a German mother and an American stepfather, who had lived in the United States until 1970, working for U.S. Senator Hubert Humphrey, among other things. Petra K. Kelly had developed close ties in her

U.S. years with one of the principal new Anglo-American antinuclear organizations created by McGeorge Bundy’s Ford Foundation, the Natural Resources Defense Council. The Natural Resources Defense Council included Barbara Ward (Lady Jackson) and Laurance Rockefeller among its board members at the time. In Germany, Kelly began organizing legal assaults against the construction of the German nuclear program during the mid 1970s, resulting in costly delays and eventual large cuts in the entire German nuclear plan.

POPULATION CONTROL BECOMES A U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY ISSUE

In 1798 an obscure English clergyman, Thomas Malthus, professor of political economy in the employ of the British East India Company’s East India College at Haileybury, was given instant fame by his English sponsors for his ‘Essay on the Principle of Population.’ The essay itself was a scientific fraud, plagiarized largely from a Venetian attack on the positive population theory of American Benjamin Franklin.

The Venetian attack on Franklin’s essay had been written by Gianmaria Ortes in 1774. Malthus’ adaptation of Ortes’ ‘theory’ was refined with a facade of mathematical legitimacy which he called the ‘law of geometric progression,’ which held that human populations invariably expanded geometrically, while the means of subsistence were arithmetically limited, or linear. The flaw in Malthus’ argument, as demonstrated irrefutably by the spectacular growth of civilization, technology and agriculture productivity since 1798, was Malthus’ deliberate ignoring of the contribution of advances in science and technology to dramatically improving such factors as crop yields, labor productivity and the like.

By the mid-1970s, as an indication of the effectiveness of the new propaganda onslaught from the Anglo-American establishment, American government officials were openly boasting in public press conferences that they were committed ‘neo-Malthusians,’ something for which they would have been laughed out of office a mere decade or so earlier. But nowhere did the new embrace of British Malthusian economics in the United States show itself more brutally than in Kissinger’s National Security Council.

On April 24, 1974, in the midst of the oil crisis, the White House national security adviser, Henry Alfred Kissinger, issued National Security Council Study Memorandum 200 (NSSM 200), on the subject of ‘Implications of Worldwide Population Growth for U.S. Security and Overseas Interests.’ It was directed to all cabinet secretaries, the military Joint Chiefs of Staff as well as the CIA and other key agencies. On October 16, 1975, on Kissinger’s urging, President Gerald Ford issued a memorandum confirming the need for ‘U.S. leadership in world population matters,’ based on the contents of the classified NSSM 200 document. The document made Malthusianism, for the first time in American history, an explicit item of security policy of the government of the United States. More bitterly ironic was the fact that it was initiated by a German-born Jew. Even during the Nazi years, government officials in Germany were more guarded about officially espousing such goals.

NSSM 200 argued that population expansion in select developing countries which also contain key strategic resources necessary to the U.S. economy posed potential U.S. ‘national security threats.’ The study warned that, under pressure from expanding domestic populations, countries with essential raw materials will tend to demand higher prices and better terms of trade for their exports to the United States. In this context, NSSM 200 identified a target list of 13 countries singled out as ‘strategic targets’ for U.S. efforts at population control. The list, which was drawn up in 1974, is instructive. No doubt, as with other major decisions of Kissinger, the selection of countries was made after close consultation with the British Foreign Office.

Kissinger explicitly stated in the memorandum, ‘how much more efficient expenditures for population control might be than [would be funds for] raising production through direct investments in additional irrigation and power projects and factories.’ British nineteenth-century imperialism could have expressed it no better. By the mid-1970s, the government of the United States, with this secret policy declaration, had committed itself to an agenda which would contribute to its own economic demise, as well as bringing untold famine, misery and unnecessary death throughout the developing sector. The 13 target countries named by Kissinger’s study were Brazil, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria, Mexico, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Turkey, Ethiopia and Colombia.

Thank You for Being Part of Our Community

Your presence here is greatly valued. If you've found the content interesting and useful, please consider supporting it through a paid subscription. While all our resources are freely available, your subscription plays a vital role. It helps in covering some of the operational costs and supports the continuation of this independent research and journalism work. Please make full use of our Free Libraries.

Discover Our Free Libraries:

Unbekoming Interview Library: Dive into a world of thought-provoking interviews across a spectrum of fascinating topics.

Unbekoming Book Summary Library: Explore concise summaries of groundbreaking books, distilled for efficient understanding.

Hear From Our Subscribers: Check out the [Subscriber Testimonials] to see the impact of this Substack on our readers.

Share Your Story or Nominate Someone to Interview:

I'm always in search of compelling narratives and insightful individuals to feature. Whether it's personal experiences with the vaccination or other medical interventions, or if you know someone whose story and expertise could enlighten our community, I'd love to hear from you. If you have a story to share, insights to offer, or wish to suggest an interviewee who can add significant value to our discussions, please don't hesitate to get in touch at unbekoming@outlook.com. Your contributions and suggestions are invaluable in enriching our understanding and conversation.

Resources for the Community:

For those affected by COVID vaccine injury, consider the FLCCC Post-Vaccine Treatment as a resource.

Discover 'Baseline Human Health': Watch and share this insightful 21-minute video to understand and appreciate the foundations of health without vaccination.

Books as Tools: Consider recommending 'Official Stories' by Liam Scheff to someone seeking understanding. Start with a “safe” chapter such as Electricity and Shakespeare and they might find their way to vaccination.

Your support, whether through subscriptions, sharing stories, or spreading knowledge, is what keeps this community thriving. Thank you for being an integral part of this journey.

The Anglo-American partnership has had two fundamental focuses for the past 130 years: to keep Germany from overtaking it and to maintain its monopoly on the lifeblood of the world, oil.

Flippin adore Engdahl he's an amazing researcher and writer. His 2005 article about Bird Flu & Biotech Bonanza is a favorite current link to give folks a reality check w bird flu redux. https://web.archive.org/web/20121025210346/https://www.globalresearch.ca/bird-flu-a-corporate-bonanza-for-the-biotech-industry/1190

Since Whitlam coup in Australia got a passing mention and another seldom noted favorite point in history for me a fab short history too from far less known but amazing WikiLeaks researcher Gary Lord.

https://jaraparilla.blogspot.com/2012/08/lessons-of-history-cia-in-australia.html